Acquiring Classic Microscopy Books on a Limited Budget

What literary resources do professional, amateur and hobbyist microscopists use for information to guide them in further developing their skills and interests? When it comes to theory and techniques, we generally seek the most current published sources of information, which are likely to keep us abreast of the best scientific and technological knowledge available. Internet resources are abundant, and of course, there are many journals and recently published books on general microscopy and specialized topics that are available. Newer books, still in print, are recognized as topically comprehensive and current but also somewhat expensive.

Fortunately there is also a wealth of printed material in the “used books” category. These books are not always current, but they have several features that recommend them. They offer a wealth of still-useful information to the microscopist; they are a revealing window into the history of microtechnique; and they are cheap – or free. This article is about this latter resource and some surprising gems. There are just too many to cover in one article, so from time to time we will publish additional articles with reviews of groups of these classic works on special topics.

For financial and security reasons, amateur microscopists (and I include in this group students, hobbyists, and off-duty professionals) often find themselves in limiting circumstances similar to those in which the earliest microscopists developed their insights and techniques. Even though there are vastly more professional resources and technical options now than there were 150 years ago, amateurs do not always have ready access to them. So they are likely to scour attics and libraries for any help they can get, “reinventing the wheels” of their own trade. It might help, therefore, to begin with a few words about how all this got started, and how it evolved to its present mode of access.

Like most technical advances, microscopy started out as an amateur activity. After the invention of the microscope sometime around 1608, there was a period of over two hundred years when compound microscopy was primarily the province of the wealthy leisured classes, along with a few stalwart (and lucky) researchers. Microscopes were individually crafted from brass and glass, had little uniformity, and were prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthy. Printed monographs related to the subject matched this select audience – published and circulated in limited quantities and generally collected in private libraries.

In the mid-nineteenth century all this changed, largely because of the industrial revolution, which made precision manufacturing possible and, for the first time, introduced standardization into the fabrication of lenses and mechanical parts. Carl Zeiss produced his first microscope in 1847, and not long after that Leitz, Bausch & Lomb, and Spencer followed with their own offerings. Printing and publishing followed suit. Research involving microscopes and the microscopic world exploded, and book publishers starting printing reference and text-books on the subject for a wider academic and research audience.

Many of these late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century books are remarkable records of painstaking work done by researchers on microscopes and microscopy techniques. There are clear indications of the trial-and-error methods of the early microscopists, using available items like household knives and razors, lamps and candles, glassware and dishes, and kitchen cooking supplies (gelatin, salt, flour, etc). As chemistry revealed the secrets of the material world, microscopists immediately applied these to their occupation. Dyes and stains, originally meant for cloth, were adapted and chemically engineered to reveal specific tissue and cellular structure of plants and animals. And there is no shortage of inventions by microscopists themselves. Many such experiments and discoveries peek out from the pages of early microscopy manuals and completely disappear from the later ones.

Most of these old books have passed out of copyright and into complete obscurity, except for occasional references in a footnote or bibliography by grateful later researchers. They appear occasionally in used bookstores. Used-book websites like www.abebooks.com, www.alibris.com, and www.amazon.com will list some remarkable finds. But many are in process of turning to dust.

The amateur microscopist or hobbyist today would ordinarily be unaware of this treasury of microscopy knowledge, were it not for a recent remarkable development. It started with the advent of the micro-computer and the internet, and the work of a few idealistic book-loving people who decided to digitize out-of-copyright classic texts and make them available free to anyone with a personal computer and download capability. The program was called “Project Gutenberg,” taking its title from the original discovery of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1455, which for the first time made printed biblical texts available to the general public.

Since then thousands of classic out-of-print or out-of-copyright books have been scanned and made available in digital form on the internet. In fact whole libraries are now engaged with this process. This is a valuable resource for microscopists, and puts them in touch with hundreds of free books with a wealth of information that is still interesting and useful today.

Besides (1) the still-active Gutenberg Project, two other internet resources are worth being bookmarked by every serious microscopist: (2) the Internet Archive and (3) its Google Books equivalent.

Books at these websites are available for free download and direct viewing, in a number of e-text formats. As thoroughly explained on the Internet Archive page, these formats include:

- Flip Book format

- Adobe Acrobat PDF – standard file viewable with free Adobe Acrobat Reader

- Adobe Acrobat PDF BW – a black-and-white version of the file, usually smaller in size

- DJVU – an open format for scanned documents

- Plain ASCII text

The file sizes for these books are fairly large, so unless a broadband or fast internet connection is used, the download will be long and slow. The resulting file also takes up a fair amount of storage space on a smaller hard drive, so it might be advisable to burn such files to a CD-ROM or DVD disk. The files require special viewing programs like Adobe Acrobat Reader to access the texts, but these are generally available as free downloads.

It is also worth noting that most microscopy-related texts have pictures, diagrams, tables and graphs, and such things do not show up at all in the plain ASCII text. To see these it is necessary to view them in their PDF format. On the other hand, the ASCII text file size is much smaller, so loading and searching for text or terms using a standard word processing program is much quicker. The problem here is that the optical character recognition phase of the scanned text introduces numerous errors into the resulting ASCII text conversion. Therefore, these texts require judicious reading and editing – a problem which the “picture” type PDF files do not have.

So what sort of books are there to download and examine? For starters, we suggest doing a search at any of the above websites with the word “microscope” or “microscopy” in the search box. A list of available texts will appear and downloading the text is a couple mouse clicks away. Try it!

Here are four books everyone should have in their virtual library:

(1) Peter Gray, Handbook of Basic Microtechnique, published in 1958.

http://www.archive.org/details/handbookofbasicm1958gray

This is a classic short textbook primarily aimed at microscopists working in clinical hospital or university laboratories, but of universal interest to all microscopists. Histology technicians have used this manual for years for basic formulas, tissue processing, sectioning, etc. It is full of practical tips and suggestions by one of the most respected names in microscopy. It also happens to be the first microscopy book I ever owned (I bought it new in 1959).

(2) Henry Baldwin Ward and George Chandler Whipple, Fresh-Water Biology, first edition published in 1918.

http://www.archive.org/details/freshwaterbiolog00ward

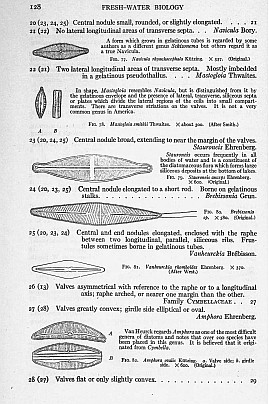

This is a long book (over 1100 pages) and therefore a very large file, but it is well worth downloading. The drawn illustrations and identification-key format is still enormously useful for microscopists trying to identify all sorts of freshwater pond life forms.

(3) Elementary Chemical Microscopy by Emile Monnin Chamot, BS, PhD (Prof of Sanitary Chemistry and Toxicology, Cornell Univ) – published in 1916.

http://www.archive.org/details/elementarychemic030675mbp.

This is a work known to all who are engaged in chemical microanalysis and is referenced by virtually every textbook of forensic analysis.

(4) Microscopy for Beginners: or Common Objects from Ponds and Ditches. by Alfred C. Stokes, MD, published in 1887.

http://www.archive.org/details/microscopyforbeg00stokiala

This is a beginner’s book that I have found not only practical but also delightfully entertaining. Here is a charming passage by Stokes about cleaning glass coverslips:

“The matter of cleaning thin glass is an important one, and unless the ‘knack’ is soon learned, the beginner will be surprised at the rapidity with which his covers will disappear. This skill, however, is readily attained. The writer has had the same thin square of No. 1 glass in use for three months continuously… and in the end he became quite attached to it as to a good friend. But a hasty move while cleaning it, or a little undue pressure, finally sent it on the way that thin covers often travel. … It was probably a wrinkle in the muslin that ruined my three months’ old pet cover. But a punishment is a good thing sometimes; the microscopist who should begin to think that he was skilful enough to avoid breakage of covers for more than three months might become insufferably conceited and a nuisance to his friends.” (pp 29-30).

So you see, in recommending these books to readers of Modern Microscopy, it is clear that we have in mind not only improving your understanding of microtechnique. We are also looking out for the development of your character. We would not want our readers to be insufferably conceited and a nuisance to their friends!

So go out there and break a coverslip. And download some free books!

Glenn Shipley Ph.D, MT(ASCP)

glennshipley@comcast.net

Comments

add comment