An Exchange in Locard’s Own Words (Part 2)

Translated by Kathleen Brahney

Commissioned by McCrone Associates, Inc.

Edmond Locard

Doctor of Medicine, Professor of Law, Director of the Lyon Laboratory of Police Techniques,

Vice-President of the International Academy of Criminology

Manual of Police Techniques

Third Edition, Completely Revised and Augmented.

Paris: Payot, 16 Boulevard St. Germain, 1939

Part II—Traces from Breaking and Entering

Chapter III

L. BREAKING AND ENTERING MARKS

- Making molds: Marks made by tools used to break into wooden doors and drawers are usually found in the parts that are stationary: i.e., for single doors, there will be marks in the doorframe; for double doors, there will be marks on the door that remains fixed. For drawers, there will be marks in the cabinet. One can make prints using modeling wax which is somewhat hard) by softening it first in the palm of the hand and then applying it forcefully to the mark. One must not use wax that is too soft, as this will adhere to the splinters of the wood. After the wax has hardened, which will happen quickly, it is then removed. In addition, it is good to photograph the mark using the millimeter rule.

- Identification: Every metallic cutting blade, even a new one, will have notches due to the sharpening process. These become exaggerated and more numerous with use. Identifying the tool used for breaking and entering and of the mark it leaves can be of great probative value, provided that the instrument has not been used or has been used very little in the intervening time; failing that, one will only be able to compare the dimensions of the blade with the print, which is very weak evidence.One can compare the suspect instrument directly with a photograph or with a mold, or—better yet—with a secondary cast of fine Plaster of Paris made from the original mold. One can also run the instrument over a piece of wood that is of the same hardness as the damaged furniture or door, thus making a set of experimental prints. Also, if the edge of the instrument is smooth, one can scrape the edge over a piece of glass covered with typographic ink, or—even better—in all cases, one can run it over a block of stearin or paraffin, or over a block of pewter. In this way, one will obtain a mark of each notch, in its width as well as its depth.One sometimes finds paint flecks left in the wood or metal surface of the damaged item. This paint can be used for comparative analyses.

- Dynamometer: Bertillon has constructed an apparatus used to measure the force needed to make marks in wood identical to the marks left at the scene. The “dynomameter” or “force-meter” yields interesting results in the cases of substantial use of force. It allows one to establish when the criminal displays abnormal strength. But this method is very costly for cases which are, all in all, quite exceptional.

- Blowtorches: The marks used by an oxyacetylene torch are indicative of the hand that has used it. One can make a wax mold or photographs of the marks: the width of the oscillation is constant for any given hand. Using this method, one can determine whether the same person has carried out two break-ins.

- False Keys: The opening of locks with false keys or hooks usually leaves exterior marks consistent with metal scrapings. These marks should be photographed. One should then dismantle the lock, where there will be metallic debris, and pieces of the hook if it is broken; in any case, there will be marks left by the false keys that have left scratches on parts of the lock.

- Church Boxes: Thieves who specialize in robbing church poor boxes use pieces of whalebone or sticks tipped with glue which they use to fish out coins or bills. This glue is made from mistletoe berries or resin, or even from holly bark. Traces of this glue on stolen items can be identified by using ruthenium red, which turns mucilage ruby red. One can also use Sudan Red No. 3 warmed in a solution of 70% alcohol, which turns glue red and cannot be washed out. Glue can also sometimes be mixed with flaxseed oil.

- Faked Break-Ins: One can detect false break-ins above all by noting the direction of footprints going from inside the site to the outside, and through fingerprints, which will be those of the person reporting the crime. In addition, the position of glass debris from broken windows will have to be interpreted. For that reason, it is important to photograph everything in place without changing anything. If the lock or the striking plate of a lock has been pulled out, one will be able to tell if the screws have been removed first by looking for three signs: a) There is no wood debris in the threads of the screws if they have not been forcibly removed; b) The slot of the screw head might have traces of recent marks from a chisel or a screwdriver; c) The chisel may have slipped, leaving marks on the metal or even in the plaster or wall paper around the screws.

M. OBJECTS LEFT BEHIND BY THE CRIMINAL

The criminal may have left objects behind or might deliberately leave traces of his presence on the scene.

- Tools: Tools used in breaking and entering will be compared to the marks found at the scene. Fingerprints will also be taken, but noting that wrought iron (in jimmying tools or crowbars) will never reveal fingerprints.

- Lighting: Very often one finds bits of candles or tallow; candle remnants may be excellent sources for indented fingerprints (for determining candle or wax stains. Sometimes one can track down the origin of matches found on the scene.

- Papers: Look for fingerprints on papers. In addition, the printed text or handwritten material might furnish precious clues. Finally, it is not unusual to use torn pieces of paper found on the scene to match with complementary fragments found at the suspects home or on his person.

- Ropes: One can research how the rope has been used, if it is identical to a sample taken from the suspect and if the knots used indicate the profession of the person who has made them.When one encounters an individual who has been bound and gagged, one must always keep in mind that this might be a set-up. In reality, a gag is never effective, and the only truly serious means of binding is by tying the elbows behind the body, using a short piece of stout cord (as the executioner would do in leading a person to the guillotine). It is only in the case of elderly women that one can believe that a case of binding and gagging has not been simulated.

- Good-Luck Charms: Often criminals, through superstition, will leave behind a lump of feces at the scene of a theft or a murder because they believe that as long as something coming from their own body remains at the scene, they are immune from being captured. This custom of defecation, far from being a good-luck charm for those who practice it, in more than one case has led to the identification of the suspect. Sometimes, criminals using this tactic will have left fingerprints on the paper they used to clean themselves up. On other occasions, the fecal matter will contain parasites that the criminal is carrying. Further, the criminal may have the stupidity to clean himself with a piece of paper that can be used to identify him (such as a birth record or an announcement of his release from prison).

- Various Objects: The list of objects left behind

is limitless. A murderer was once identified using a piece of bread left at the scene; the crust of the bread revealed a defective oven, leading to the identification of a baker who fit the description of guilty person. One finds buttons, pieces of cloth, photographs, gloves the criminal has used in order to keep from leaving fingerprints at the scene, suitcases, bags and food provisions (fruit has been found that was bitten into or cakes that have been partially eaten), pharmaceutical products, tobacco, packages from which the string or the paper can be studied, bits of wood, etc. - Automobile Debris: In case of homicides or injuries resulting from automobiles being used in hit-and-run cases, one can identify the car or the driver by the objects or decries left behind at the moment of impact or subsequently dragged along by the vehicle. Certain cases have been resolved by analyzing dust; others have made use of the analyses of stains or small bits of clothing. Oftentimes, entire objects or very large fragments are used for identification. Thus, at the scene of a collision, one might find pieces from the headlights, the windshield or the running boards. Analysis of the glass fragments will be carried out using chemical and physical examinations.

N. HAIR

- Research: One might have to examine hairs, either discovered at the scene of a crime or in the case of determining whether or not a fur is an imitation. At the scene of the crime, one might find hairs:

- In the hand of the victim, in the case of hairs torn out when the victim was defending himself.

- On the aggressor, particularly under the fingernails (cases of murder or sex crimes).

- On the genital organs of the aggressor or the victim.

- At the site of a murder (hair from the head or body hair that has been pulled out) or of a theft (head hair or body hair that has fallen out or gotten caught on a given object).

The discovery of hairs from the victim is always possible when someone is arrested, so one must always take hair samples from the victim before the body is buried (and pubic hairs in the case of sex crimes.)

- Examination techniques: The hair is first micro-photographed without any special preparation. It is then dehydrated by immersing it into pure alcohol for a few minutes. It is then mounted on Canadian balsam. Microphotographs will be taken not only of the middle zone of the hair, but also of the point and the follicle, if possible.

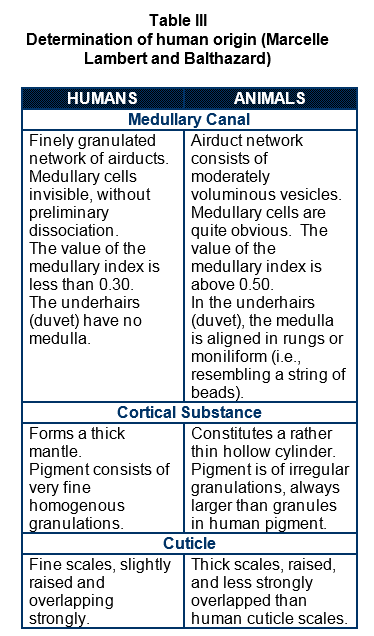

- Determination of whether the hair is of human origin: Here is a resume of the findings of Marcelle Lambert and Balthazard:

Various Types of Body Hair:

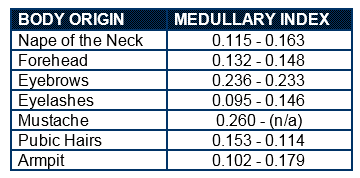

Hair from various parts of the body can be identified by the medullary index, that is, the relationship between the diameter of the center core of the hair with respect to the diameter of the entire hair at the thickest part of the hair. Here are Oesterlen’s results:

Table IV

Range of Medullary Index of Hair from Various Parts of the Body

(Oesterlen’s Results)

In general, the diagnosis of the region of the body the hair is from can be refined more or less as described by Marcelle Lambert and Balthazard.

- Individual Identification: One keeps in mind the condition of the end of the hair, aspects of the root, the diameter, the pigmentation (pigment that is diffuse in red hair, granular in gray, chestnut or brown hair) and the pattern of the scales. Men’s haircuts are characterized by layering. The distance between two layers or between the last layer and the free ends of the hair can reveal how recently the hair has been cut, by allowing about 2 to 5 mm every ten days (Pincus.) One can recognize hairs that have been pulled out by the presence of a cellular coating around the base, or by the fact that the base is open on the bottom, that is, the hair is still in its developing stage.

EDITOR’S NOTE

Locard follows on with Part III: Dust Traces

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edmond Locard, Treatise on Criminalistics.

Hans Gross, Handbuch fur Unterschungsricher, Munich, Schweitzer, 1908; the same has been translated into French, translated by Bourcart and Wintzweiller, Paris, Marchal and Billard, 1899.

R.A. Reiss, Manual of Scientific Policing, Lausanne, Payot, 1911.

Lacassagne and Etienne Martin, Summary of Legal Medicine, Paris, Masson, 1921.

Edmond Locard, Criminal Investigation and the Scientific Method, Paris, Flammarion (n.d.)

Tomellini, Manuale di polizia giudiriazia, Milan, Heopli, 1912.

Marcelle Lambert and Balthazard, Human and Animal Hair, Paris, Steinheil, 1910.

Nicolae Minovici, Manual Technic de Medicina Legala, Bucharest, Socecu, 1904.

H. Coutagne and Florence, “Fingerprints and Judicial Expertise,” Archives of Lacassagne, No. 19, 1889.

Andre Frecon, Fingerprints in General, Lyon, Storck, 1889.

E. Godefroy, Elementary Manual of Police Techniques, Brussels, Larcier, 1932.

Charles Manget, Synoptic Tables for the Analysis of Tissues and Textile Fibers, Paris, J.-B. Bailliere, 1902.

George Bertillon, Anthropomorphic Reconstruction Using Clothing Measurements, Paris Thesis, 1892.

Ainsworth Mitchell, “Circumstantial Evidence from Hairs and Fibers,” The Internal Review of Criminalistics, No. 1, July, 1929.

M. Chavigny, “Vehicle Traces,” The Internal Review of Criminalistics, No. 1, July, 1929.

Harry Soderman and Ernst Fontell, Handbok I Kriminaltecknik, Stockholm, Wahlstrom and Widstrand, 1930.

F. Louwage, Techniques in Thefts, Brussels, 1922.

John Glaister, A Study of Hairs and Wools, Cairo, Misr Press, 1931.

Popp, Die Mikroskopie im Deinst des Kriminaluntersuchung, in Arch. De Gross, 70 BD., 1918.

George Vuillemin, Dust from the Medico-Legal Point of View, Nancy Thesis, 1926.

Comments

add comment