Machining a Darkfield Insert for the Olympus 1.25 NA BH2 Condenser

Having a well-equipped home machine shop for precision machining allows me to design and build components for microscopes that are not commercially available. My interest in instrument making and machining began when I was an undergraduate research assistant at Northwestern University. The freshman engineering classes are now required to take a design class that involves building their own inventions using a student shop that has very capable machine tools. Some of these graduates are likely to have home machine shops in the future. Since most microscopists are chemists or biologists, it is unlikely that they will have a chance to learn to use machine tools as part of their university education. In the old days, the high schools had machine shop classes where future microscopists could learn how to use basic machine tools. Our “enlightened” high school education system now considers such training unnecessary for students who will continue on with a university education. Thus, unlike in the old days, young microscopists are now very unlikely to have home machine shops. We are hoping that this series of articles will encourage microscopists to start a home shop of their own.

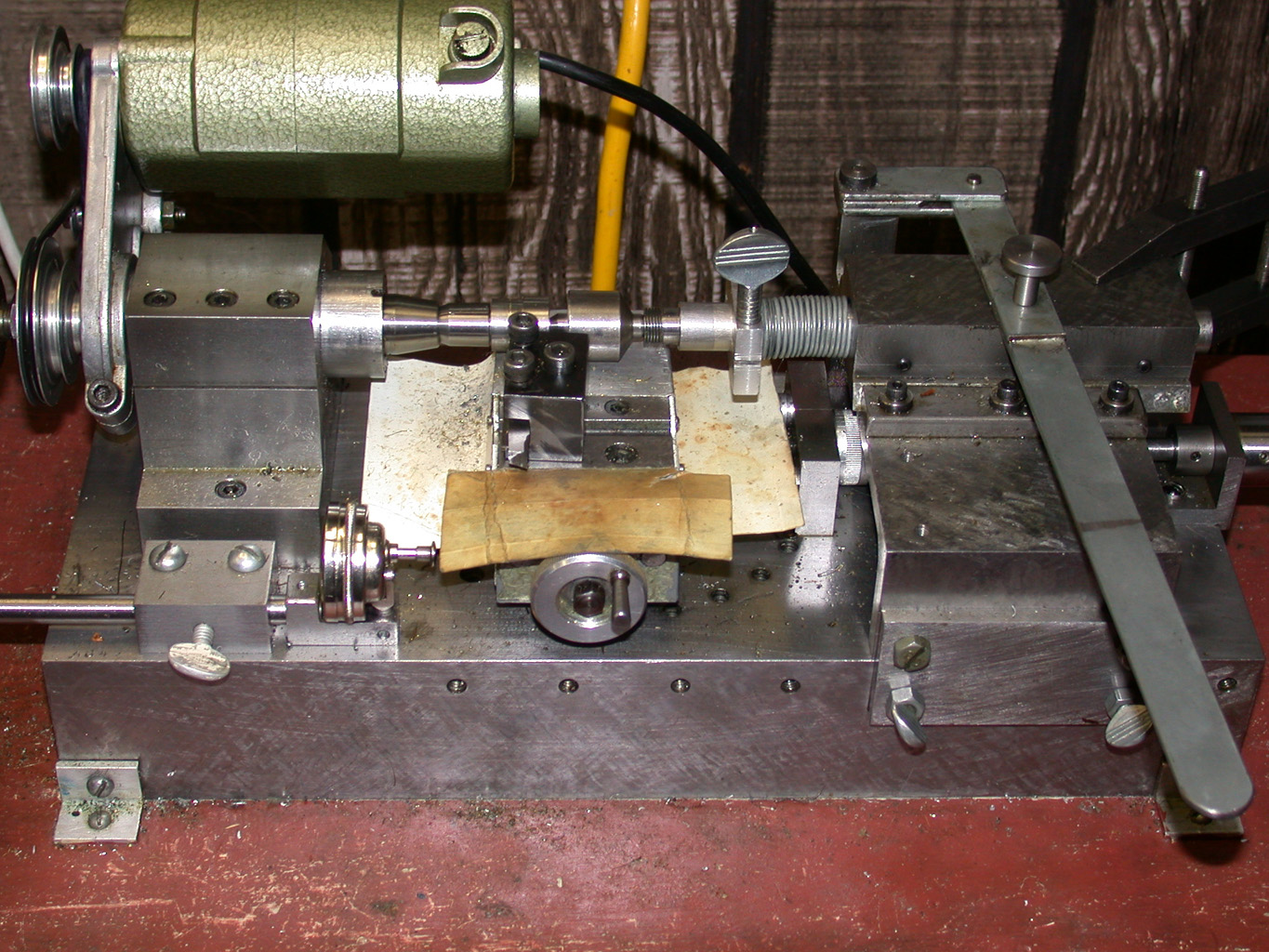

My initial home shop tool was a Unimat, the first miniature lathe, drill press, and milling machine combination for home machinists. The more recently introduced miniature machine tool systems, from makers such as Sherline Products and PRAZI, and available from a number of sources, would be suitable for microscopists wanting home shop machining capability. Figures 1 and 2 show my modified Unimat lathe being used to turn the brass shim stock stops to the correct diameter for the prototype darkfield insert.

Peter Cooke of MICA wanted this critical darkfield dispersion staining capability for the Olympus BH2 microscopes he uses for consulting and teaching microscopy courses. I rediscovered darkfield dispersion staining with a Monolux microscope which I modified so that it now has dual brightfield and darkfield capability for all of its objectives including the 60X 0.85 NA. (“Rediscovery of Darkfield Dispersion Staining while Building a Universal Student Microscope“, Microscopy Today, Jan/Feb 2003) The wire-spider-mounted darkfield stops for the fiber-optic source illumination system are precisely sized and centered to just block the NA of their mating objective. This article will show some of the machining operations used for the prototype insert made for Peter as well as the improved features of the inserts available through McCrone Microscopes and Accessories. Figure 3 shows the modified Unimat drill press drilling system and miniature dividing head used to drill the wire spider holes in the ends of the insert bodies.

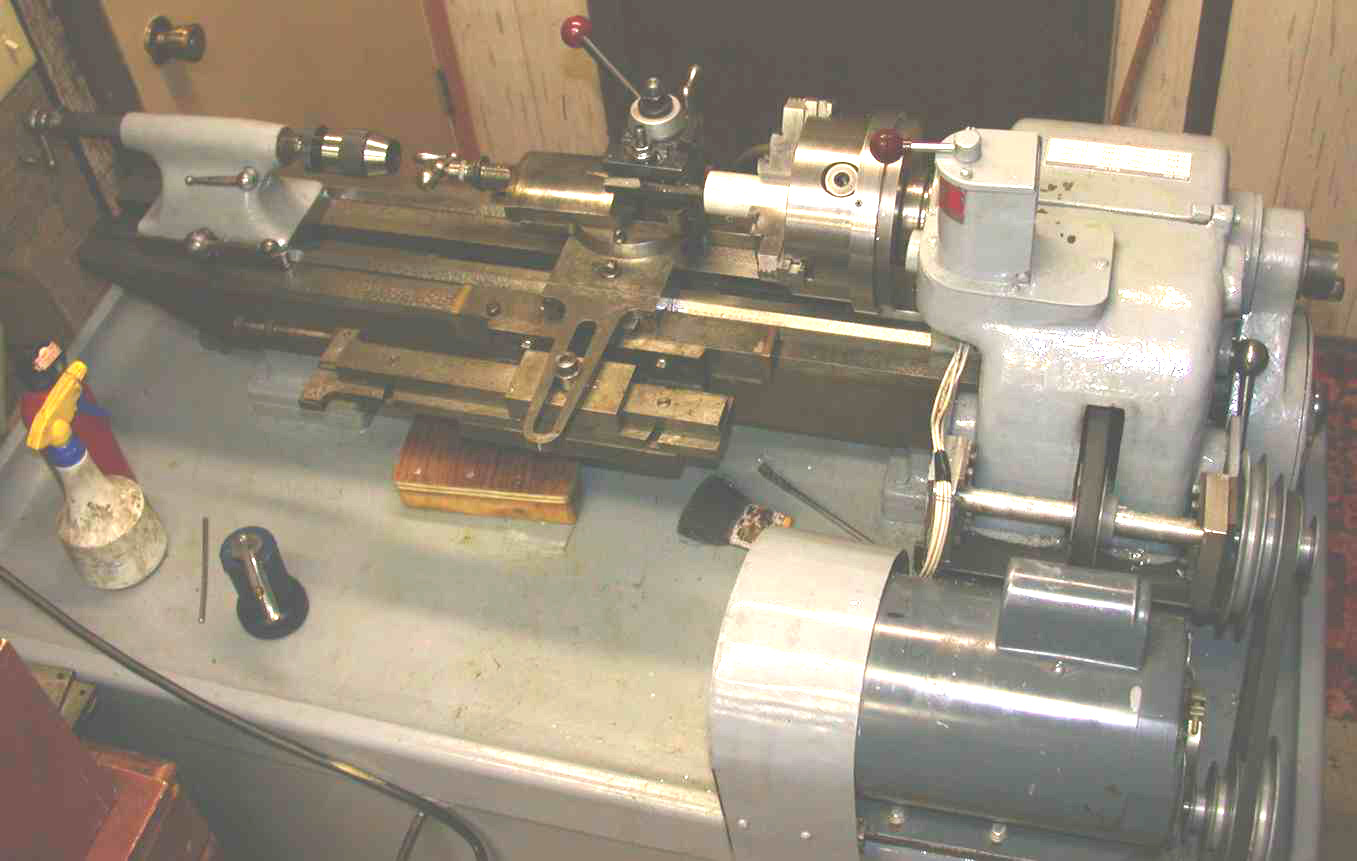

I find that a tool room lathe is very helpful for my microscope projects. Mine is a rebuilt WWII Wade 8″ lathe, with 3 and 4-jaw chucks to hold the metal stock being machined. A key feature of the tool room lathe is its capability to hold the part being machined in a precision 5C collet—a specific size of a split-band or collar type of tool-holder chuck, which is particularly accurate for gripping parts. This lathe allows me to quickly machine the larger parts, such as the insert body for the Olympus condenser. Figure 4 shows the blank for an insert body held in the 3-jaw chuck of the Wade lathe.

Likewise, a metal-cutting band saw is much more efficient than a hand hacksaw for cutting the aluminum bar stock for the insert bodies. My metal cutting band saw is a rebuilt Delta brand. Figure 5 shows the aluminum bar stock for the insert bodies being cut with the band saw. (The tool room lathe and metal cutting band saw were affordable for me because they were purchased used, and not in operating condition.)

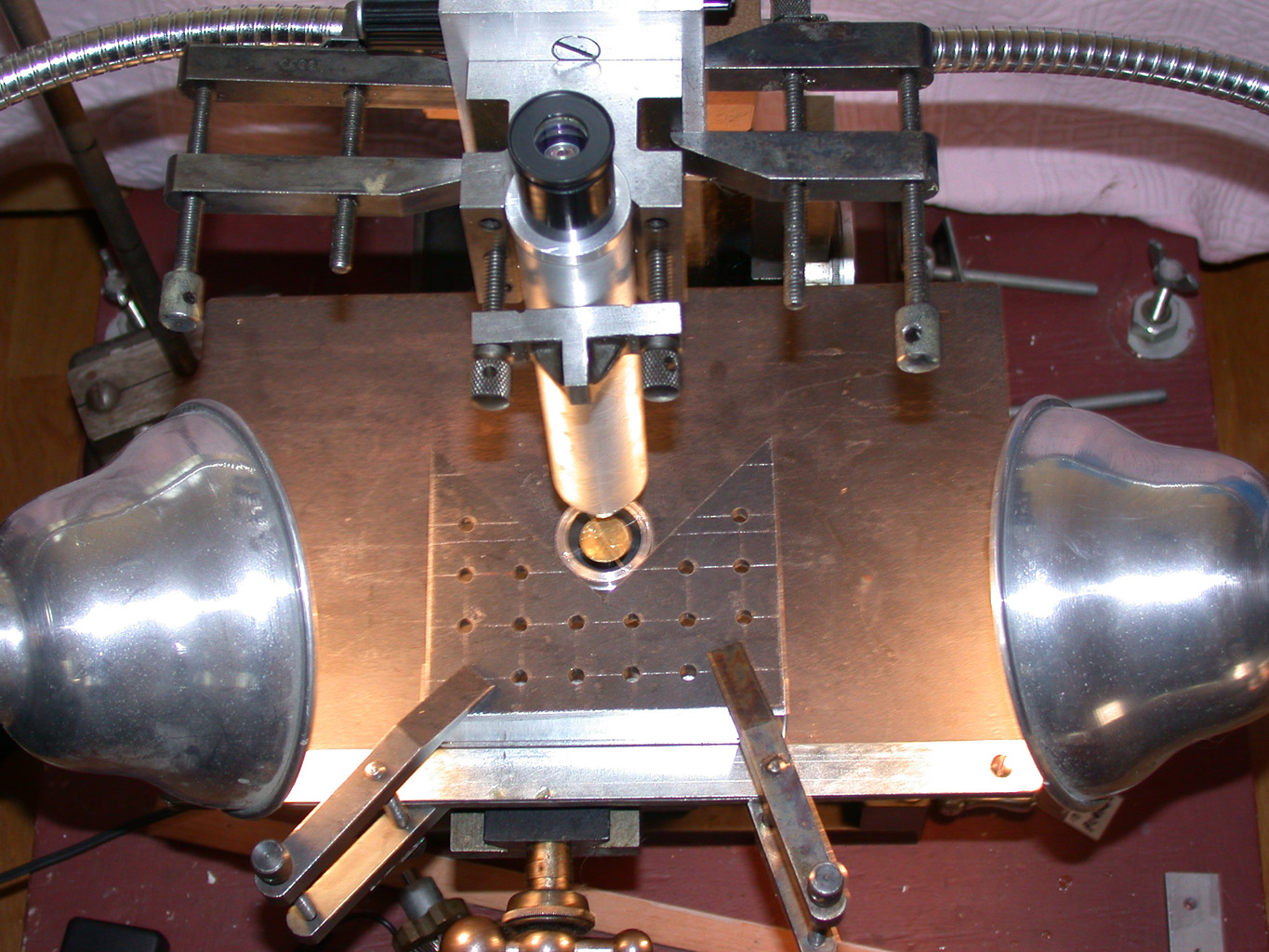

Centering of the stops in my photomicrography stand is done with the aid of a home-built microscope with a 5X objective and 10X eyepiece with a measuring graticule shown in Figure 6. The reduced diameter of the insert nose is located in a V-block as the assembly is rotated under the microscope to detect eccentricity. Drops of nail polish were used to attach the spider wires to the brass shim stock stops of the prototype design after centering.

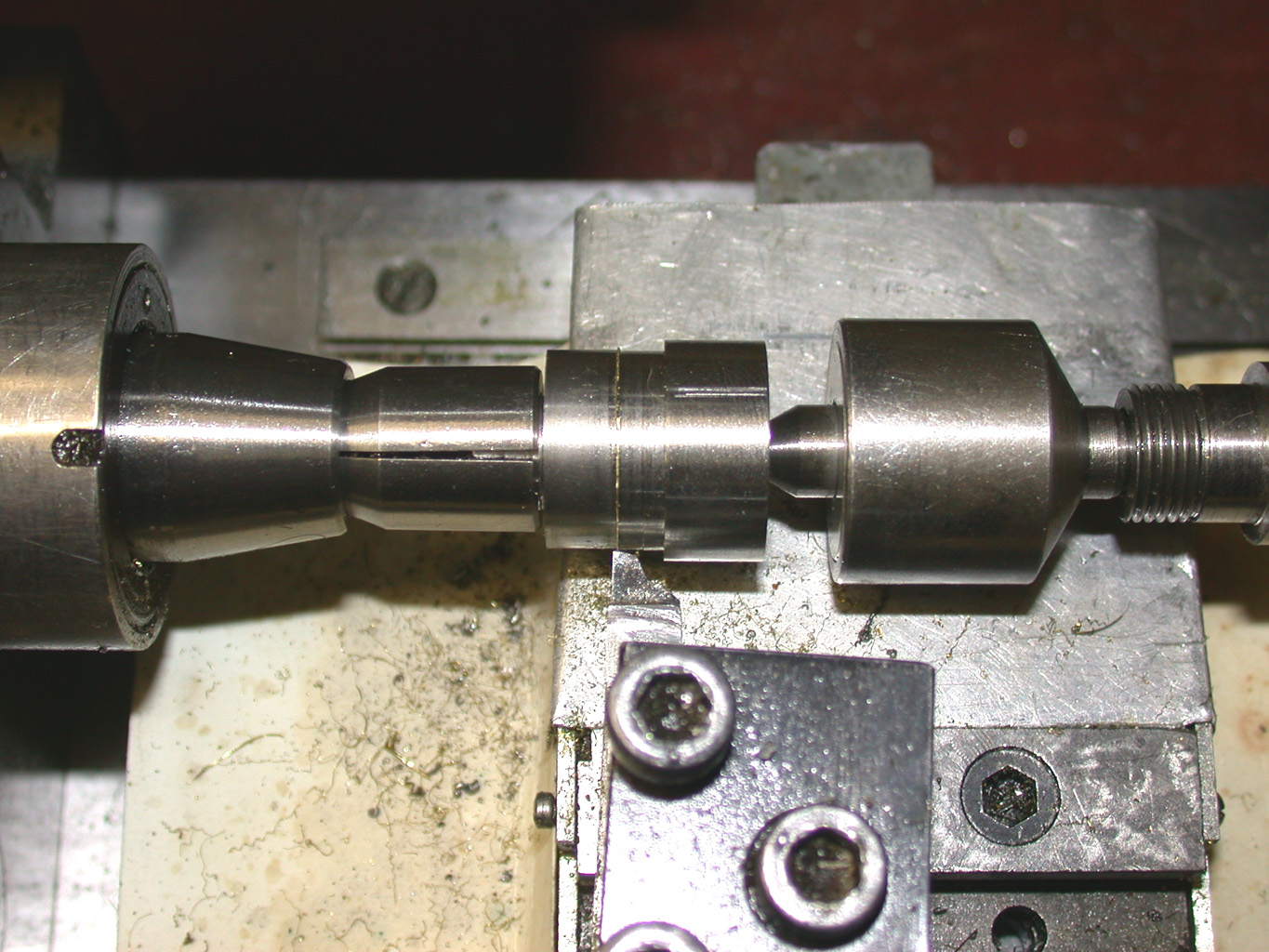

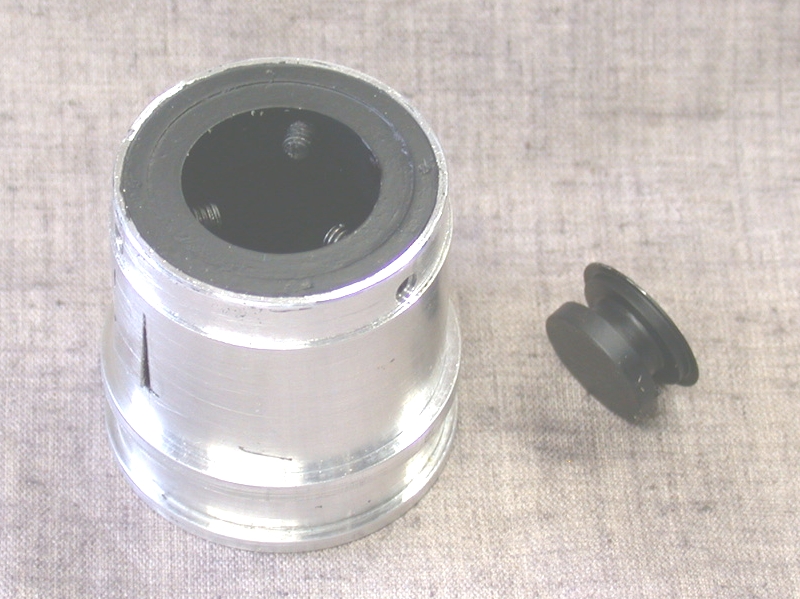

The finished prototype insert made for Peter Cooke is shown in Figure 7 along with the condenser it is fitted to, and a polarizer. The reduced diameter on the nose of the insert body is machined to be a precise fit in the inner diameter of the ring containing the iris diaphragm in the condenser. This precise fit is needed to maintain centering of the insert in the condenser. Unfortunately, a variation of over 0.25 mm was found when the rings in Peter’s four condensers were measured, so the insert bodies had to be custom fitted to each condenser and are not interchangeable. Subsequent use of the condenser inserts demonstrated that the wire spider mounting method for the stops was too fragile, and all the inserts were converted to a revised design shown in Figure 8. The construction features of the revised design are shown in Figure 9. The three set-screws mate with a groove in the one piece stop body, resulting in a rugged design to withstand shipping and handling. Centering the stop with the set-up shown in Figure 9 is much easier than with the earlier wire mounted stop. All of the surfaces that might scatter light into the condenser are painted with flat black model paint. Low production quantities do not justify the high batch cost of black anodizing the aluminum bodies and the stop used in the revised design. Black anodizing is not an operation feasible in the home shop.

There are a number of sources for equipment and information for the microscopist wishing to start a home shop. Of particular interest is the magazine, The Home Shop Machinist. A good British magazine is the Model Engineers’ Workshop. Lindsay Publications, Inc. has a catalog of unusual technical books, published in the past and present, which reveal skills and secret processes almost forgotten today. Enco is one source for machines and tools. The advertisers in The Home Shop Machinist, mentioned above, are also good sources of tools and machines. Advertised here also are a series of videos on various shop procedures, such as lathe work, milling, grinding, etc.

Comments

add comment