The Literature of Classical Microchemistry, Spot Tests, and Chemical Microscopy

The Chymists are a strange class of mortals impelled by an almost insane impulse to seek their pleasure among smoke and vapor, soot and flame, poisons and poverty; yet among these evils I seem to live so sweetly that may I die if I would change places with the Persian King.

— Johann Becher (1635-1682)

During a recent course of instruction in the microscopical identification of white-powder unknowns, a question asked was, “How can you tell the difference between sucrose and dextrose?” Another was, “How can you determine whether an alum is the potassium alum, the sodium alum, or the ammonium alum?” Questions such as these constantly come up during any microscopical identification course: “Is there a quick way to tell if aspirin is present in this analgesic?” “Is boron present in this sample of dentifrice?” “Does the paper-coating consist of cooked starch?” Microscopists trained in classical methods realize that all of these questions can be answered quickly and economically through the use of simple microchemical tests which have been developed over the last 180 years: elaborate and costly instrumentation is not necessary, even though such equipment may be available. Knowledge of these microchemical tests may be obtained from numerous reference books, and acquisition of such references should be an on-going process for the laboratory or for one’s personal professional library.

In this article I would like to survey the books that contain information on the performance of microchemical tests, including spot testing; illustrations and/or annotations are offered for each reference. The presentation will be more or less chronological so that the history of the entire branch of this microscopical science will be apparent. We will start with some definitions, and set boundaries.

Definition of Classical Microchemistry

In 1975, the American Chemical Society initiated a project to prepare a history of the Society and of the various branches of chemistry, to be published in the Society’s centennial year, 1976. At the same time, the executive committee of the Division of Analytical Chemistry decided that in addition to supplying information for such a volume, it would undertake a centennial history of its own, and thus A History of Analytical Chemistry Laitinen, H.A. and G.W. Ewing (1977)] was produced. The history of the development of microchemistry and microanalysis as a special branch of analytical chemistry for this book was prepared by Herbert K. Alber, who studied under the founders of microanalytical chemistry at the Technical University of Graz, Austria. One of these founders was Fritz Pregl 1860-1930), who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1923. Alber defines the “Classical Period of Microanalysis” as the years 1900 to about 1945, and states (p. 26) “It is generally agreed that Friedrich Emich 1860-1940) at the Technical University in Graz, Austria, was the founder of classical microchemistry.” He defines the years prior to 1900 as “The Early Microchemical Period.” In this period, he states (p. 25) that François-Vincent Raspail (1794-1878) “established himself as the founder of chemical microscopy, and he probably can be recognized as the first microchemist.”

In the Preface to the first edition of his Elementary Chemical Microscopy, É.M. Chamot (1915) stated, “…the earliest comprehensive work dealing with microchemical methods was from the pen of an American—Theodore G. Wormley—whose classic, The Microchemistry of Poisons, appeared in 1867.” [Wormley (1867)]

Some historians attribute the first microchemical analysis to Pliny (23-79 A.D.) who mentions an iron sulfate test in his 37-volume Historia Naturalis, the work in which he described the entire natural world as far as it was known in his time, but it is doubtful that the test was actually performed on very small samples, and a microscope was certainly not in use.

As a microscopist and microchemist, I define classical microchemistry as the period from the first application of chemical tests conducted while actually viewing the results with a microscope, to the general introduction of non-microscopical instrumental analysis. For me that means from Raspail’s earliest experiments (early 1820s), through, say, the 1960s – and even to the present day, for those few practicing in the classical manner.

Spot tests, or spot-testing, is understood to mean color and/or precipitate reactions resulting from mixing an unknown and a test reagent in a “spot plate”. Spot plates are small rectangular or square tiles with ~1 cm diameter depressions in which the chemical reactions are conducted; the spot plate may be made from white, blue, black, or black-and-white ceramic, or from clear glass or plastic (which may be laid on paper of any color, for contrast enhancement), and may have from one to twelve or more smooth concave depressions. A well-slide used in microscopy can be used for the same purpose.

“Chemical Microscopy” was defined by Émile Chamot in the Introduction to his Elementary Chemical Microscopy as “the application of the microscope to the solution of chemical problems” for the purpose of differentiating it from “microchemical” methods and tests. He went on to explain that “Microchemistry implies chemistry on a small scale,” and, indeed, all highly sensitive identification reactions and all quantitative methods, which permit the use of samples smaller than are commonly necessary in ‘standard methods’.” Under the term chemical microscopy, Chamot included “those methods, principles, and phenomena of chemistry which may be studied particularly advantageously by means of the microscope….”

Microchemistry and spot tests are, therefore, vital methods in the practice of chemical microscopy.

THE BEGINNINGS – 19TH CENTURY

François-Vincent Raspail

In 1814, the work of J. J. Colin (1784-1865) and H.F. Gaultier de Claubry (1792-1878) showed that iodine colors starch blue. F.S. Stromeyer (1776-1835) confirmed this test in 1815, but none of them thought to apply the test microscopically. François-Vincent Raspail (Figure 1) applied the iodine test for starches to sections of grasses, specifically for the elucidation of the development of the embryo, and published a paper on his findings in 1825. For his microscope, Raspail had the optician Deleuil in Paris build for him a small simple microscope, a modified Cuff/Ellis type. In the Spring of 1826, he found new reagents that permitted the detection of sugar, oil, and albumin within the cell. Also, he developed microchemical tests for resin and protein, all the while describing the colors and reactions.

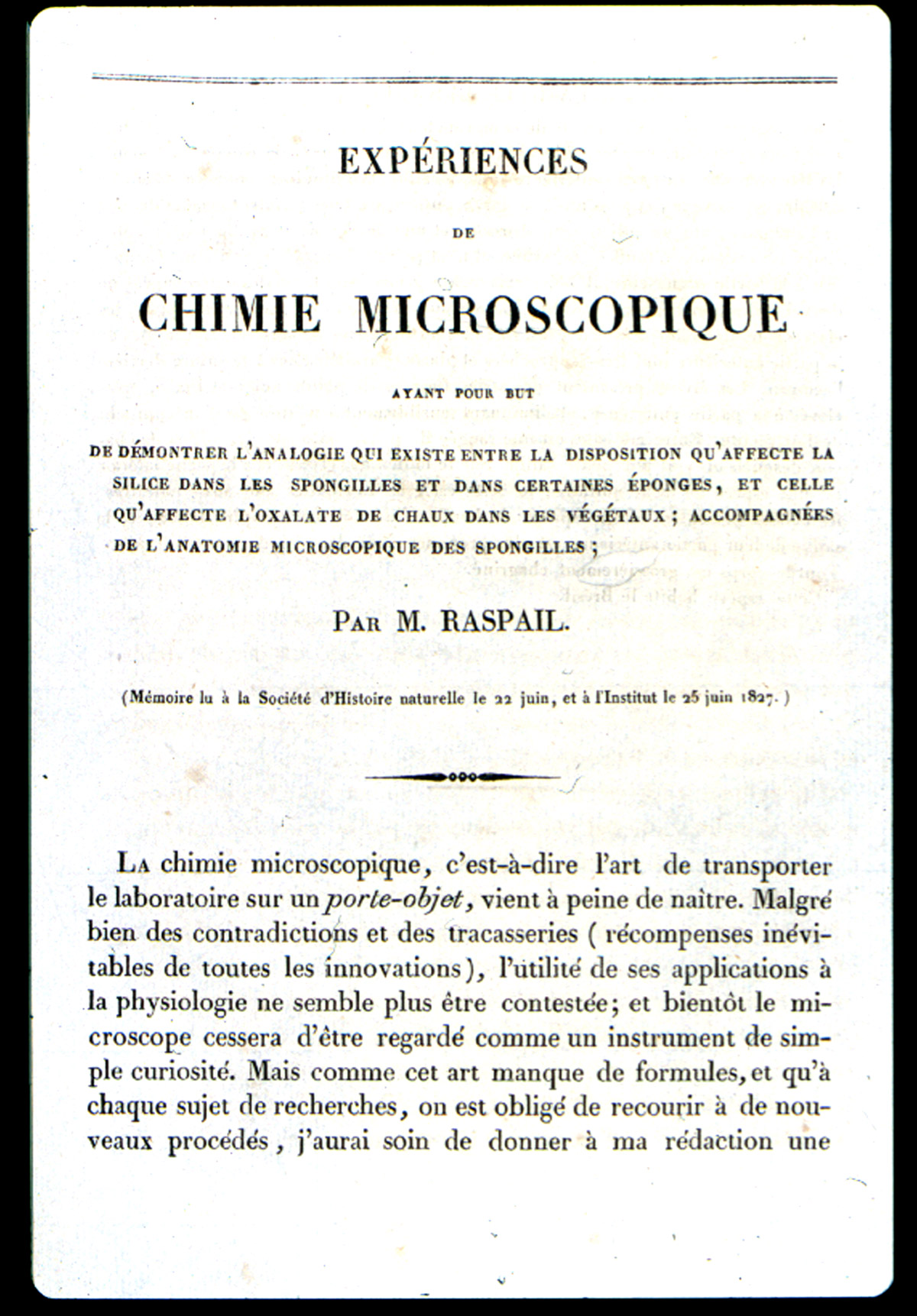

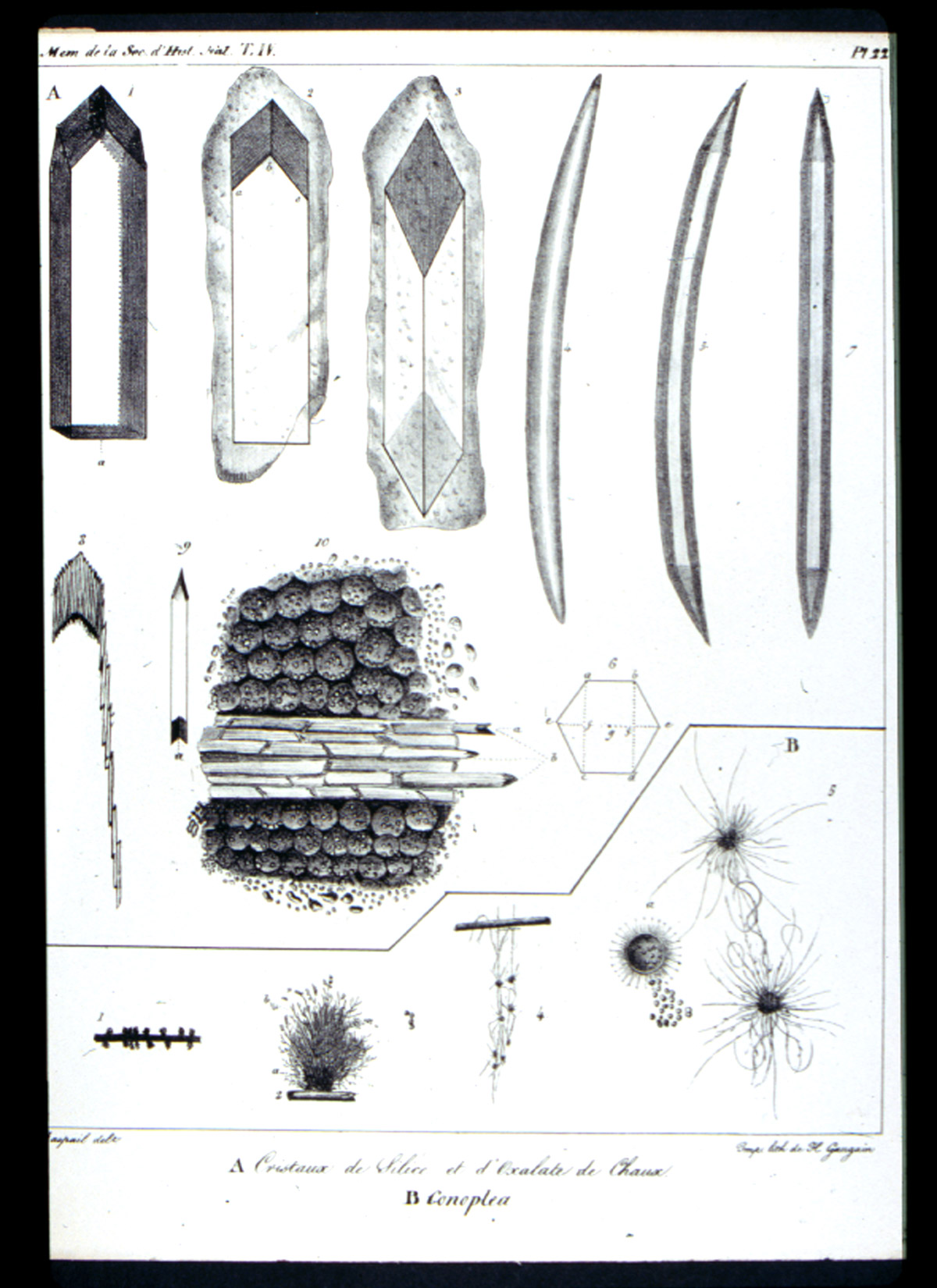

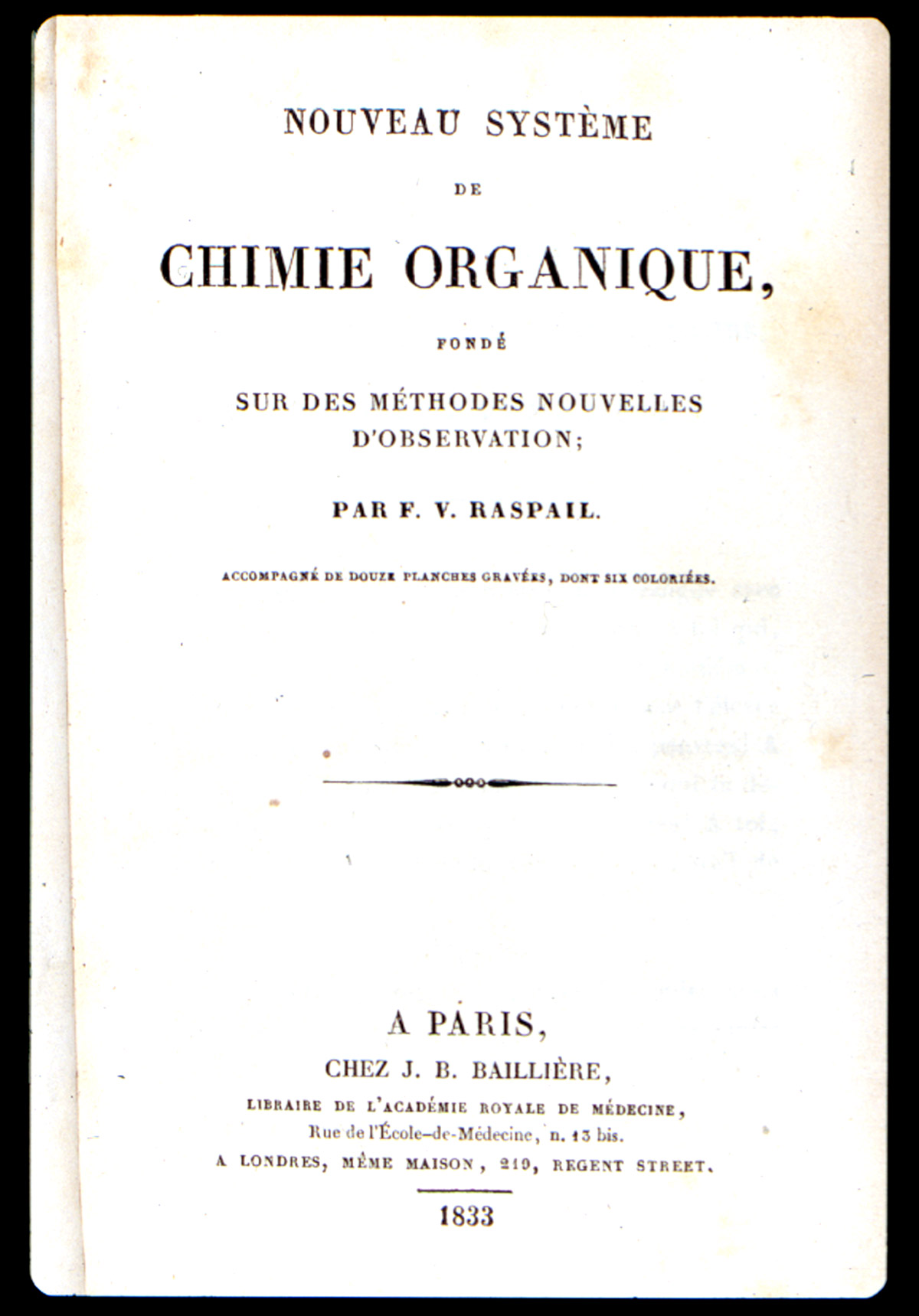

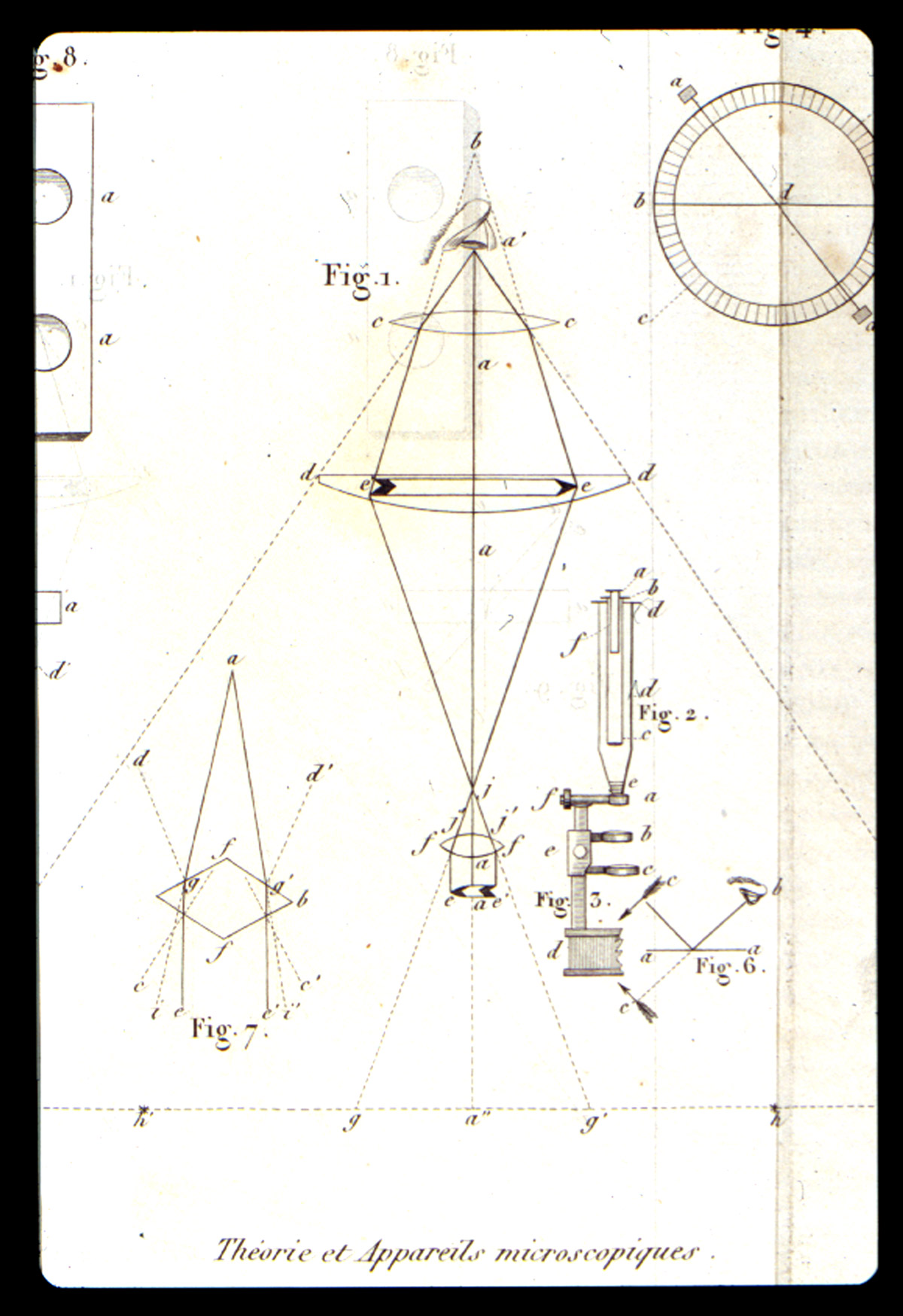

In 1827, he demonstrated the presence of silica in Spongilla, and of calcium oxalate in the starch of monocotyledons, and published his results Raspail, François-Vincent (1827)]. In this publication he introduces the term “chemical microscopy” Figure 2). One of the two plates (Figure 3) in this publication illustrates the silica and the calcium oxalate. With these and numerous other articles, Raspail founded both histochemistry and microchemistry. His series of articles culminated in the 1833 publication of his book (Figure 4), Nouveau Systeme de Chimie Organique…[Raspail, François-Vincent (1833)]. which is described in Duveen as the first work in which the microscope was successfully employed in organic chemistry. In the first chapter he discusses the theory, construction, and manipulation of the microscope, and illustrates this in one of the twelve engraved plates (Figure 5). One of the six hand-colored plates (Figure 6) illustrates microchemical reaction products and crystals found in botanical tissues. In chapter after chapter he reports the microscopical effects of employing various acids, bases, and salts to plant and animal tissue. On the basis of his chemical findings, he proposed a system of classification based on physiological function, rather than morphology, as Linnaeus had done. An English translation of this book was published in 1834 [Raspail, François-Vincent (1834)]. What makes this book particularly remarkable is the fact that it was written while Raspail was in prison. Raspail was a political activist, and spent almost three years in prison, and wrote as many books while confined. Dora B. Weiner has written an excellent biography [Weiner, Dora B. (1968)] of Raspail, and Chapter 4 is of special interest, because it was written in collaboration with Simone Raspail, François-Vincent’s great-granddaughter, who, as a modern biologist and pharmacist, repeated some of Raspail’s experiments with one of his own microscopes.

(Click on any image to view larger versions.)

Theodore G. Wormley

As already mentioned, in 1915 É.M. Chamot stated that

“…the earliest comprehensive work dealing with microchemical methods was from the pen of an American –Theodore G. Wormley.”

Theodore Wormley, M.D. (Figure 7A) was Professor of Chemistry and Toxicology in the Starling Medical College, and of Natural Sciences in Capital University, Columbus, Ohio. In 1857, he announced his intention to publish a book on the microchemistry of poisons, and a prospectus announcing its plan was published in March, 1861, at which time the drawings were almost completed. A few years afterward (1865), A. Helwig published his Das Mikroskop in der Toxikologie [Helwig, A. (1865)], but it would prove to be nowhere near the magnitude of Wormley’s book. The first edition of Wormley’s Micro-chemistry of Poisons [Wormley, Theodore G., M.D. (1867)], was published in 1867. In his Introduction, Wormley defines what he means by microchemistry: “By the term MICRO-CHEMISTRY of POISONS, we understand the study of the chemical properties of poisons as revealed by the aid of the microscope.” In the Preface, he states, prophetically, “Heretofore the microscope has received but little attention as an aid to chemical investigations, yet it is destined to very greatly expand our knowledge in this department of study.”

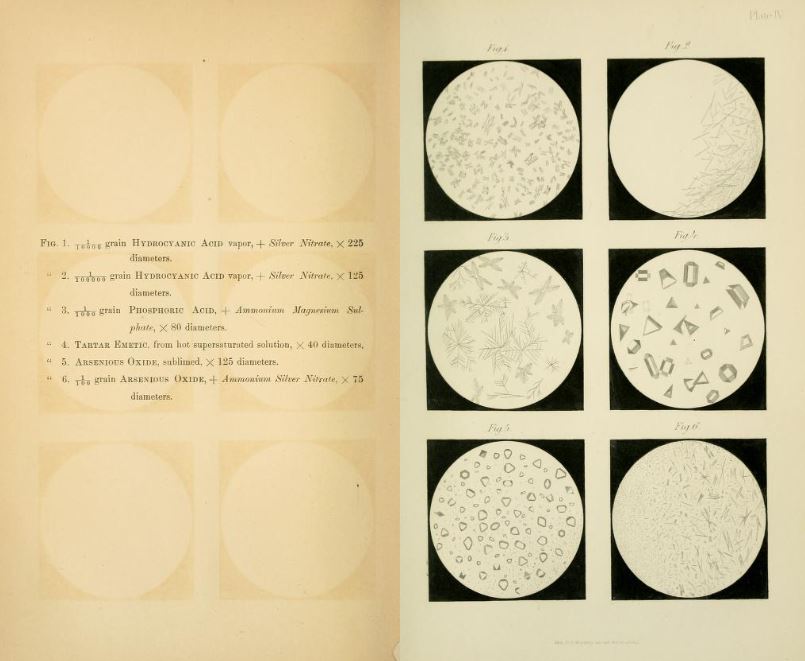

His superb book is quite large (668 pages), and contains seventy-eight illustrations engraved upon steel. Interestingly, Wormley could not find an engraver who would take on the task of engraving the microscopical images of the delicate crystalline reactions, so his wife taught herself to engrave in steel, and it was she who drew from nature and transferred to steel all of the microscopical images in the form of thirteen beautiful plates. Wormley affectionately dedicated the book to her. In the back of the book, there is a long, fold-out Tabular View of the Behavior of Alkaloids with Reagents. The described tests and Wormley’s book in general, are as valid and useful today as they were almost 140 years ago. Demand for the book was strong, and necessitated a second edition [Wormely, Theodore G., M.D. (1885)], in 1885, by which time Wormley was Professor of Chemistry and Toxicology in the Medical Department of the University of Pennsylvania. This second edition is enlarged to 784 pages, with ninety-six illustrations, an Appendix on the Detection and Microscopic Discrimination of Blood, and a chromolithographic frontispiece of blood spectra. Additional tests and case-histories were added, as well as a revision of the chemical nomenclature. Wormley’s book in either edition is highly recommended, both for its historical significance and for its still useful microchemical tests. It is found in both one and two-volume versions.

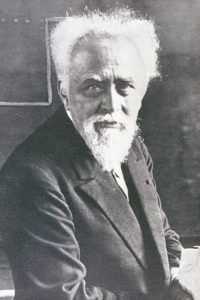

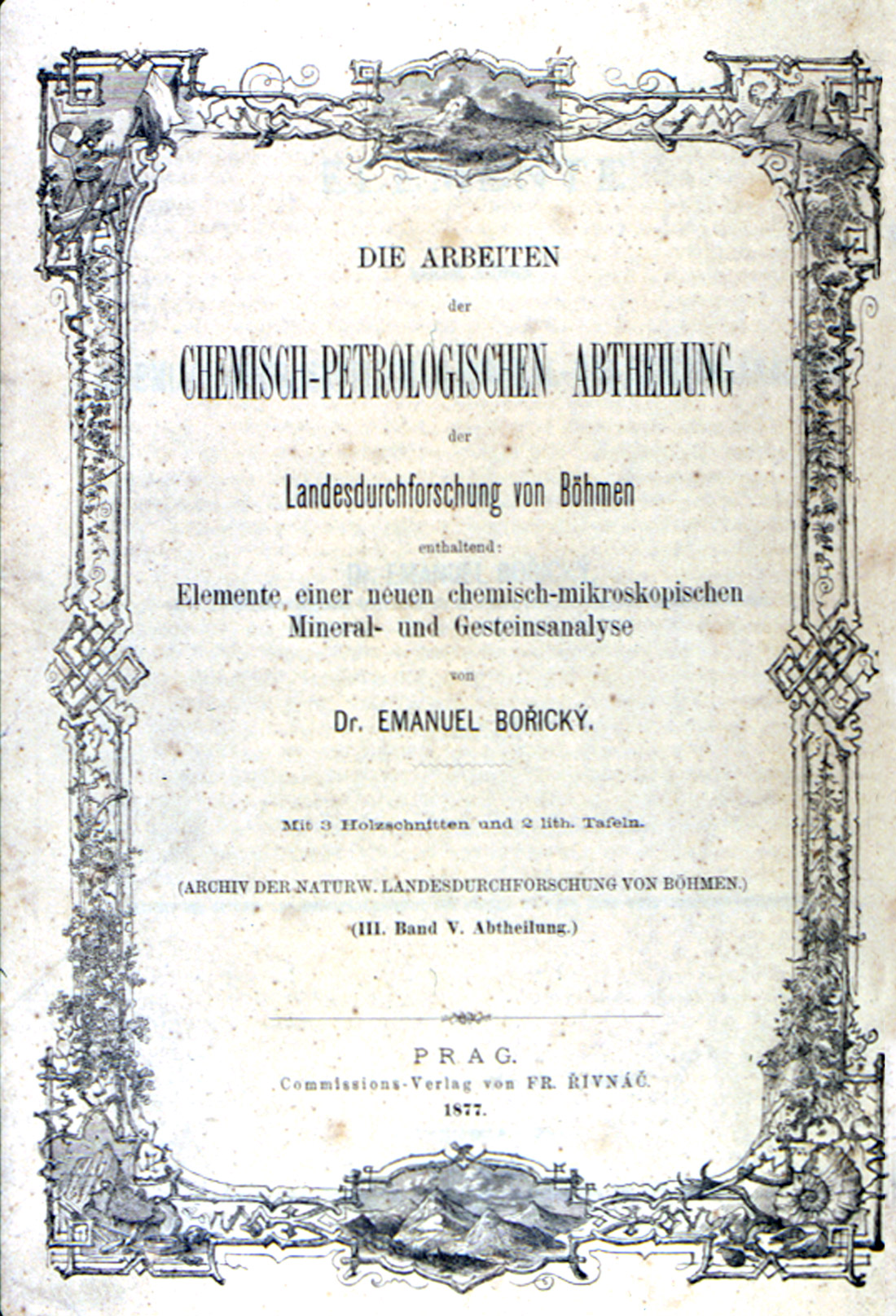

Emanuel Boricky

Emanuel Boricky was Professor Extraordinaire at the University of Prague, and Curator of the Bohemian Museum, in what is today the Czech Republic. In 1877, he published a very important contribution on the microchemical analysis of rocks and minerals. The publication (Figure 8), Elements of a New Chemical Microscopical Analysis of Minerals and Rocks [Boricky, Emanual 1877)], constituted a part of the Chemical-Petrological Division’s Natural History Investigation of Bohemia. In it, he described the removal of small samples of the mineral components of rocks, and their subsequent microchemical analysis with the aid of the microscope. The relatively short publication (80 pages) contains three woodcuts, and is also illustrated with two lithographic plates showing the microscopical appearance of the chemical reactions (Figure 9). An English translation [Winchell N.H. (1892)], of this valuable monograph was published by Professor N.H. Winchell in the Nineteenth Annual Report (1890) of the Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota (Minneapolis, 1892).

The practical microscopist will not have a need for this publication, which, like Raspail’s works, are of considerable interest, but they are essential items in the library of those microscopists interested in the historical development of their craft.

A. Streng and K. Haushofer

A few years prior to the 1867 publication of Wormley’s full-length book on the microchemistry of poisons, there had been several individual articles on microscopical reaction products with poisons, and several test reagents, as we know from Wormley’s Preface. It may be added that after the death of Boricky, subsequent microchemical methods were devised by Behrens, Streng, Haushofer, Rénard and Klément, and others.

Professor A. Streng of Giessen published several journal and yearbook articles in the years 1883 through 1886 on the subject of microchemical analysis of the more common minerals occurring in crystalline rocks, just as Boricky had done, but Streng applied microchemical investigations to compounds of some elements that had not previously been investigated in this way, and he added several valuable reactions. Moreover, he perfected the accessories and manipulations of microchemical work. For Streng, microchemical reactions were a valuable auxiliary method to microscopical observations of ground and polished rock sections, and to blowpipe analysis. In addition to his journal/yearbook articles of 1883-1886, Streng incorporated microchemical analysis in his book, Anleitung zum Bestimmung der Mineralien (Giessen, 1890).

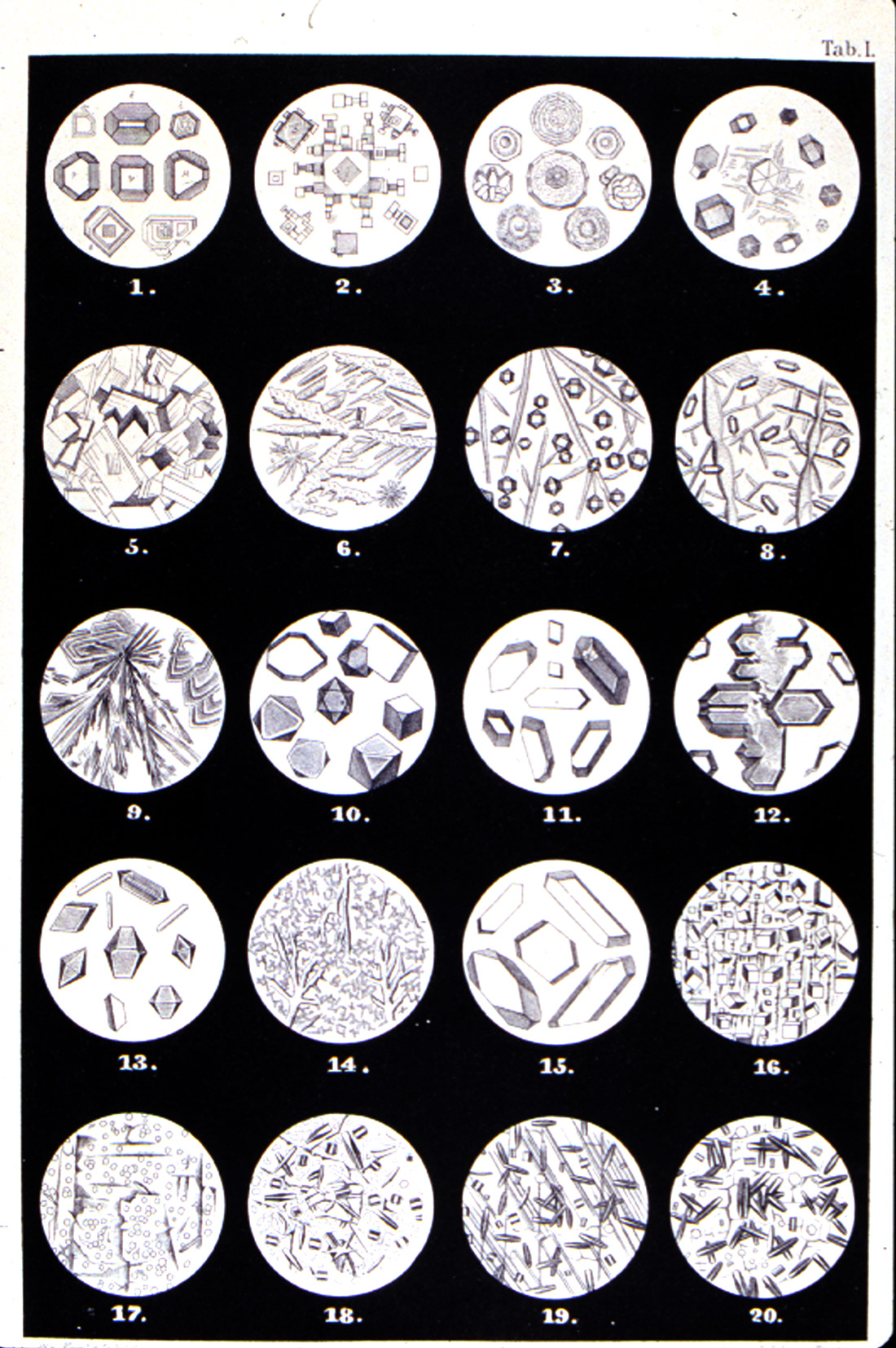

K. Haushofer went a step farther when, in 1885, he published his now “very rare” Mikroskopische Reactionen [Haushofer, K. (1885)], which was a manual (Figure 10) for distinguishing the majority of the elements, but he regarded the microscopical reactions (Figure 11) as supplementary to ordinary qualitative analysis. The importance of his work was the attempt to bring all elements, even the rare ones, within the range of microscopical analysis.

Klément and Rénard

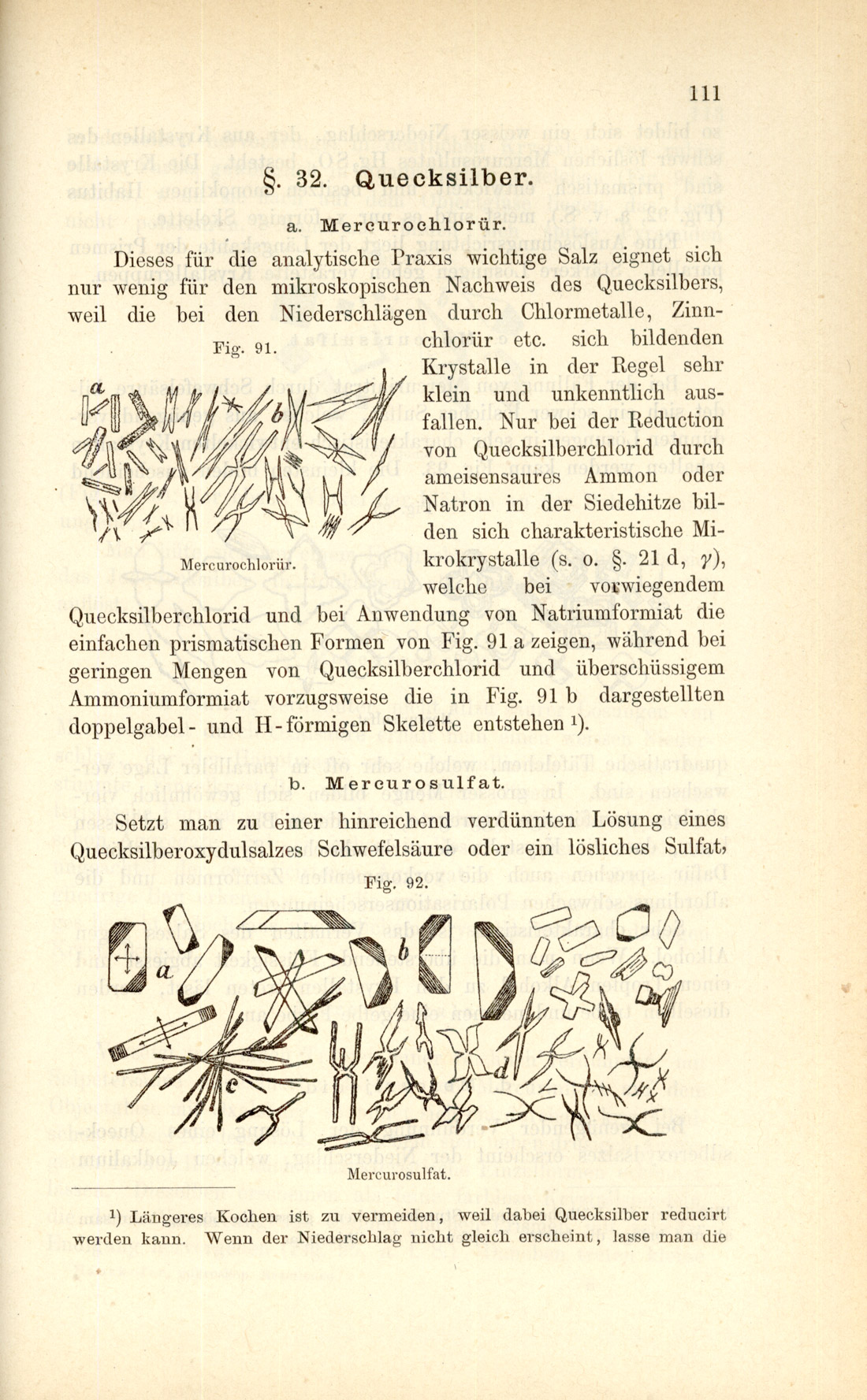

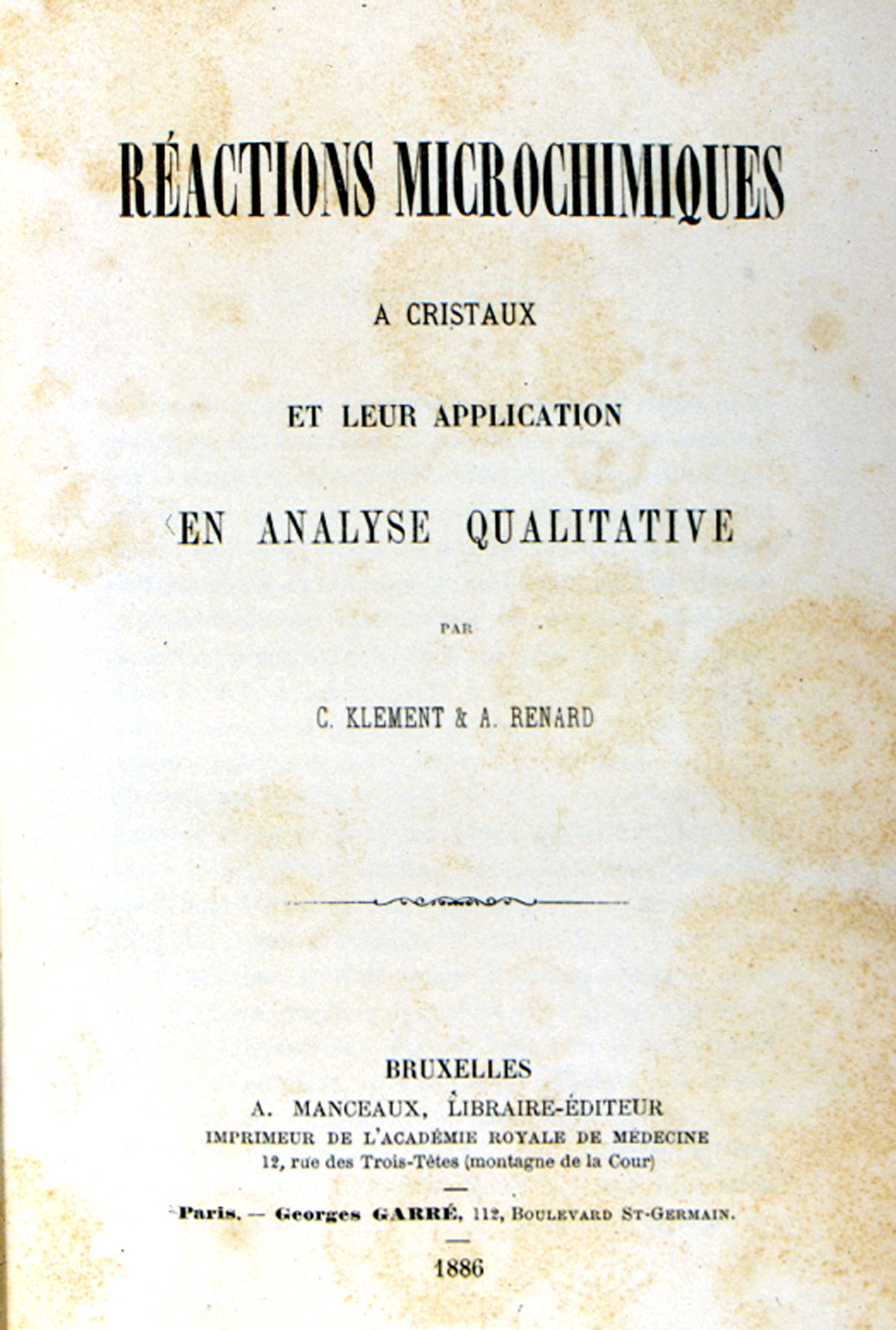

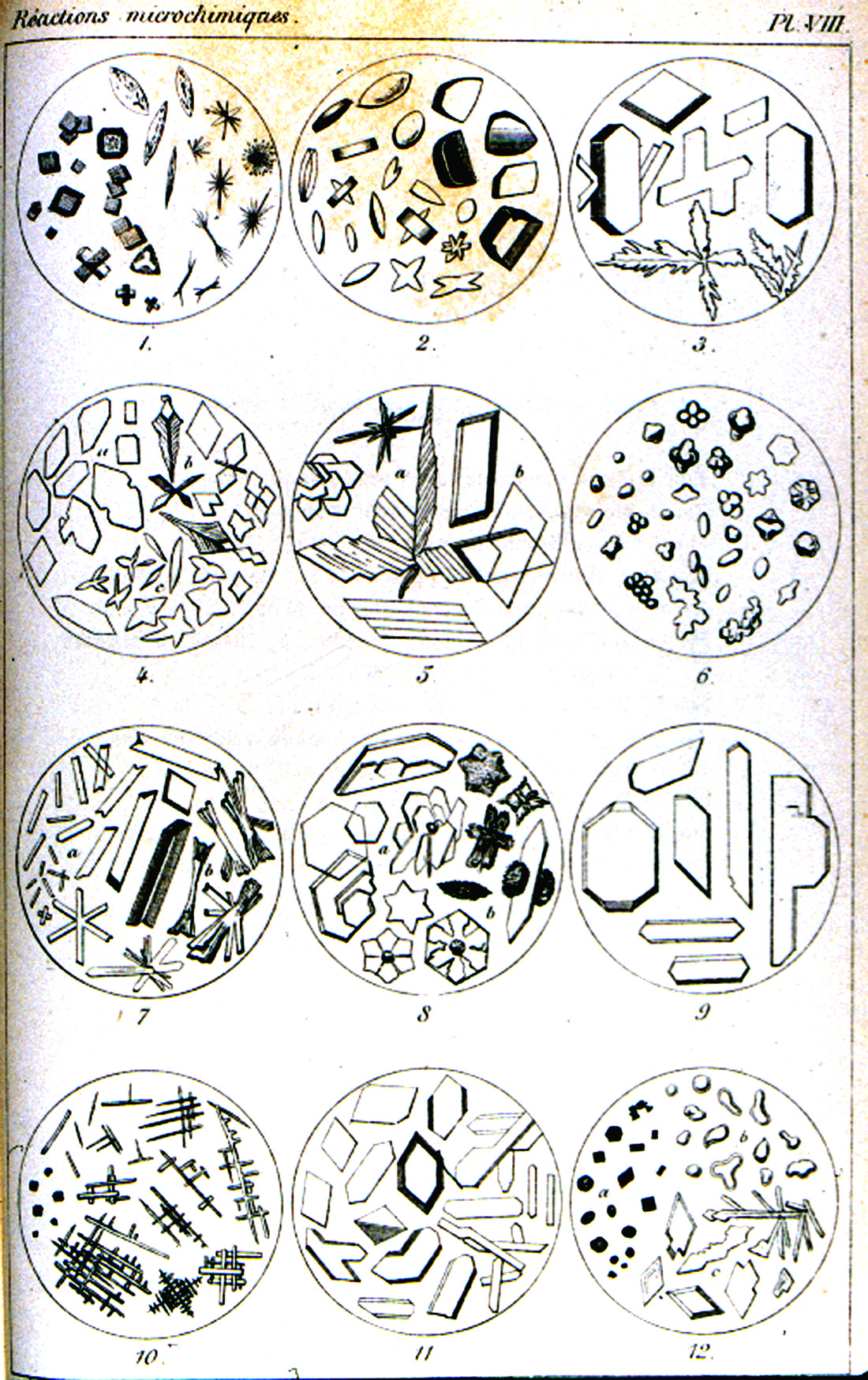

The treatise of Klément and Rénard, Reactions Microchimiques; A Cristaux et Leur Application en Analyse Qualitative [Klément, C. and A. Rénard (1886)], published in 1886, is on a level with Haushofer’s manual. This work (Figure 12) abstracts all of the microchemical tests known at that time. It is also accompanied by numerous literary references, and a table of 54 elements, with references to the text pages. There are eight engraved plates, each with twelve microchemical reactions illustrated. The illustrations are delicately engraved and each chemical reaction product is shown in a full range of crystal habits and distortions (Figure 13).

Unfortunately, the expectations suggested by the second part of the text title are not quite satisfied. As with Haushofer’s manual, the foundation of a microscopical analysis is here, but when it comes to discriminating between closely allied elements, such as cobalt and nickel, or zinc and cadmium, the tests leave much to be desired. Still, both works are closer to a complete microscopical analysis.

Cristaux et Leur Application en Analyse Qualitative (1886).

reactions in Klément and Rénard’s Reactions Microchimiques; A Cristaux et

Leur Application en Analyse Qualitative (1886).

H. Behrens

A serious source of error in all microchemical methods is the fact that slight differences in the conditions under which crystallization takes place may profoundly affect the form and appearance of the crystals produced during a reaction: the acidity or alkalinity needs to be controlled in a number of cases; the concentrations of test substances and/or reagents may be important; and there are the cases which interfering ions must first be removed. The microchemical tests published up to this point in our survey were full of these problems. Furthermore, there were still several gaps in Klément and Rénard’s collection of reactions, and Professor Streng’s manual did not have a means for detecting cadmium or nickel.

Professor H. Behrens (Figure 14) at the Hochschule in Delft, Holland directed his efforts to removing the sources of error in the published tests, and introducing many new and elegant methods. In addition to rigorously testing all the older reactions and methods, he added the data he obtained on the reliability and limits of applicability of the tests, as well as appending his notes and cautions to his accounts of the various reactions. He also added tests for the rarer elements that were only then being found to be more widely distributed in the earth’s crust than was formerly supposed. Behrens wrote articles on his microchemical methods in Dutch, German, and French.

Professor John W. Judd, of the Royal College of Science, London had been using microchemical methods for mineral identification in the Geological Laboratories of that institution. He learned of them when he met Boricky while on a visit to Prague in 1875, two years before Boricky’s monograph appeared. Later, Professor H. Behrens decided to translate his own book on microchemical analysis into English, and asked Professor Judd for his cooperation in bringing out this new edition. Thus far, there had been no books in English on this subject except for Wormley’s treatise, which was devoted to poisons, and so Professor Judd did not hesitate to accede. And, thus, in 1894, we see the publication in English of, A Manual of Microchemical Analysis [Behrens, H. (1894)], to which Professor Judd contributed an Introduction. This is a very nice book to own – not absolutely necessary, because the tests will be in Chamot and Mason, but from an historical perspective, you may enjoy critical comments, such as (page 101), “Haushofer has tried to develop staining of gelatinous silica with fuchsine… into a microchemical test. It is not of sufficient delicacy for this purpose; besides, the stain, recommended by me for specimens of rocks, is of no use for gelatinous silica suspended in a liquid.”

Behrens ends the century with the 1899 publication of his Anleitung zur mikrochemischen Analyse, and will open the new century with still another work.

Meanwhile, in America, a young man, Émile Monnin Chamot, from Buffalo, New York, entered Cornell University in 1887, graduated with a B.S. in 1891, and qualified for the Ph.D. in 1897. His interests were in toxicology and sanitary chemistry, and he had been introduced to the application of microscopy to chemistry by Professor George Caldwell, the first head of the Chemistry Department there. As was customary at the time, Chamot then went abroad for post-doctoral work. He spent a year at the University of Nancy training in toxicology with Mace, and in Delft studying inorganic qualitative analysis with Professor Behrens. On his return to America, and as the century closes, Chamot initiated a series of papers on microchemical analysis that appeared in the Journal of Applied Microscopy, starting in 1899.

Before leaving the 19th century, it would be well to note that there were very important, parallel developments going on, such as Otto Lehmann’s introduction of hotstage methods, Michel-Lévy’s interference color chart, advances in optical crystallography, and even other microchemical methods in botany and physiology (urinary sediments, etc.).

TWENTIETH CENTURY

The new century starts out strong: Behrens publishes his Mikrochemische Technik [Behrens, H. (1900)], and Huysse’s beautiful Atlas is produced.

A. C. Huysse

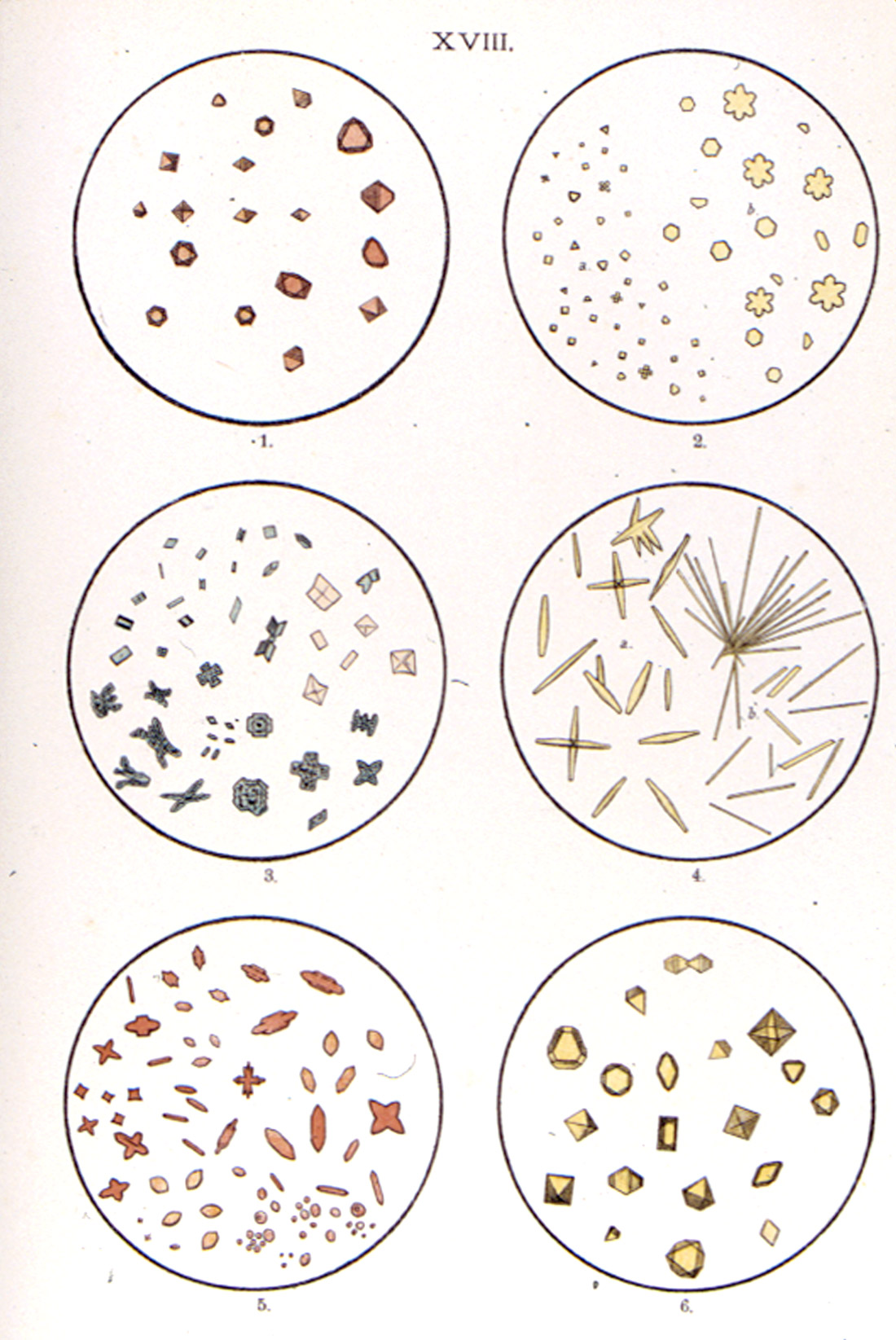

Huysse was a military pharmacist in the Royal Netherlands Army. 1900 saw the publication of his Atlas zum Gebrauche bei der mikrochemischen Analyse [Huysse, A.C. (1900)] (Figure15). It was written for chemists, pharmacists, geologists and metallurgists, and for university and technical school laboratories. The beauty of this publication lies in the 27 chromolithographed plates, each illustrating six microchemical reactions (Figure 16); some are in black-and-white, but most are in color, even down to the variegated green interference colors in yellow lead iodide (Plate XIII).

A second edition [Huysse, A.C. (1932)], of this beautiful Atlas (Figure 17) was published in 1932, with the chromolithographs (Figure 18) now numbering 31.

Atlas zum Gebrauch bei der mikrochemischen Analyse (1900).

microchemical reactions, from A.C. Huysse’s Atlas zum Gebrauche bei der mikrochemischen Analyse (1932).

CARL G. HINRICHS

Gustavus Detlef Hinrichs was Professor of Chemistry in the Medical Department of St. Louis University. In the first couple of years of the new century, he planned the publication of a work on microchemical analysis which would not require the use of hydrogen sulfide. He requested his son, Carl Gustav, a chemistry instructor in the same medical department—in fact the youngest instructor—to work out such a course. The resulting book, First Course in Microchemical Analysis [Hinrichs, Carl Gustav (1904)], was published in 1904, simultaneously in St. Louis, Missouri; New York and Leipzig; London; and in Paris. It is a curious book. The father wrote the introduction to crystallographic chemistry. There is a Crystal Atlas, with plates of hand-drawn crystals, illustrations of microscopes and goniometers, two portraits, and several graphs. Then there is an Atlas of Micro-crystals, carefully drawn, as they appeared in the field of a microscope; some are hand-drawn, others are taken from works of other authors. The plates occupy 64 pages. The father’s introduction (pages 65-100) is followed by the son’s course (pages 101-145).

Probably only those interested in the historical aspects of microchemistry will require this book.

N. SCHOORL (UTRECHT)

Schoorl’s name comes up around the first decade of the century. He published a number of articles on microchemical analysis in the years 1907-1909, which were collected together in book form as Beiträge zur mikrochemischen Analyse [Schoorl, N. (1909)].

J. DONAU (1877-1960)

Dr. Julius F. Donau’s Die Arbeitsmethoden der Mikrochemie….[Donau, Julius (1913)] was published in 1913. This book (Figure 19) constituted Volume IX of a more comprehensive Handbook der mikroskopischen Technik, published by the editors of Mikrokosmos. The first part of this slim book is devoted to qualitative microchemistry, and the second part introduces quantitative methods.

FRIEDRICH EMICH (1860-1940)

In his rectoral address at the Technical University in Graz, Austria in 1899, Emich described his philosophy of working with milligram amounts of material. He started with qualitative techniques for both inorganic and organic microanalysis. He developed new microcrystal tests conducted on microscope slides, developed fiber tests for nanogram amounts of acid, alkali, boron, and sulfide, and developed the techniques for working in glass capillaries, not only for identification, but for the preparation of organic compounds.

He improved techniques for working in capillary cones, elementary tests for organic compounds, fractional distillation, boiling point determination, and many other techniques which today go under the name of his co-workers only. Emich’s main interest, however, was in quantitative microanalysis. His gravimetric procedures with milligram amounts of material, using newly developed micro-balances, were shown to be as reliable as macro-procedures. He is today recognized as the founder of quantitative microanalysis —both inorganic and organic; however, the Nobel Prize would be awarded to F. Pregl, who adopted Emich’s methods.

The first edition of Emich’s Lehrbuch der Mikrochemie [Emich, F. 1911)], was published by Bergmann in Wiesbaden in 1911. The second edition came out in 1926 [Emich, F. (1926)]. The first edition of Emich’s Mikrochemisches Praktikum [Emich, F. (1924)], was published in 1924, with a second edition in 1931 [Emich, F. (1931)].

H. BEHRENS AND P.D.C. KLEY

1915 was a memorable year in microchemistry, because Behrens and Kley published their book on organic qualitative microanalysis, and Chamot published the first book version of his text on chemical microscopy. Let us start by going back to before the turn of the century, when young Émile Chamot first went to Delft and met Behrens. As it turned out, Behrens at the time was providing his new assistant, P.D.C. Kley (Figure 20), with detailed instruction in inorganic qualitative microscopical analysis, and Chamot was fortunate in being included in the instruction. On leaving Behrens, Chamot asked how he might repay the valuable instruction, and was told by Behrens to start courses in this field in America. Kley stayed on as Behrens’ assistant, and together they authored the Organische mikrochemische Analyse [Behrens, H. and P.D.C. Kley (1915)], which was published by Voss in Leipzig in 1915. Several other editions followed, the fourth edition appearing in 1921/1922. This fourth edition was translated into English by Richard E. Stevens, and published in 1969 [Behrens, H. and P.D.C. Kley (1969)].

bench in Delft. Cropped section of portrait from McCrone Research Institute Museum.

der Mineralien (1915), Part 2 of Behrens-Kley Mikrochemische Analyse.

TUNMANN

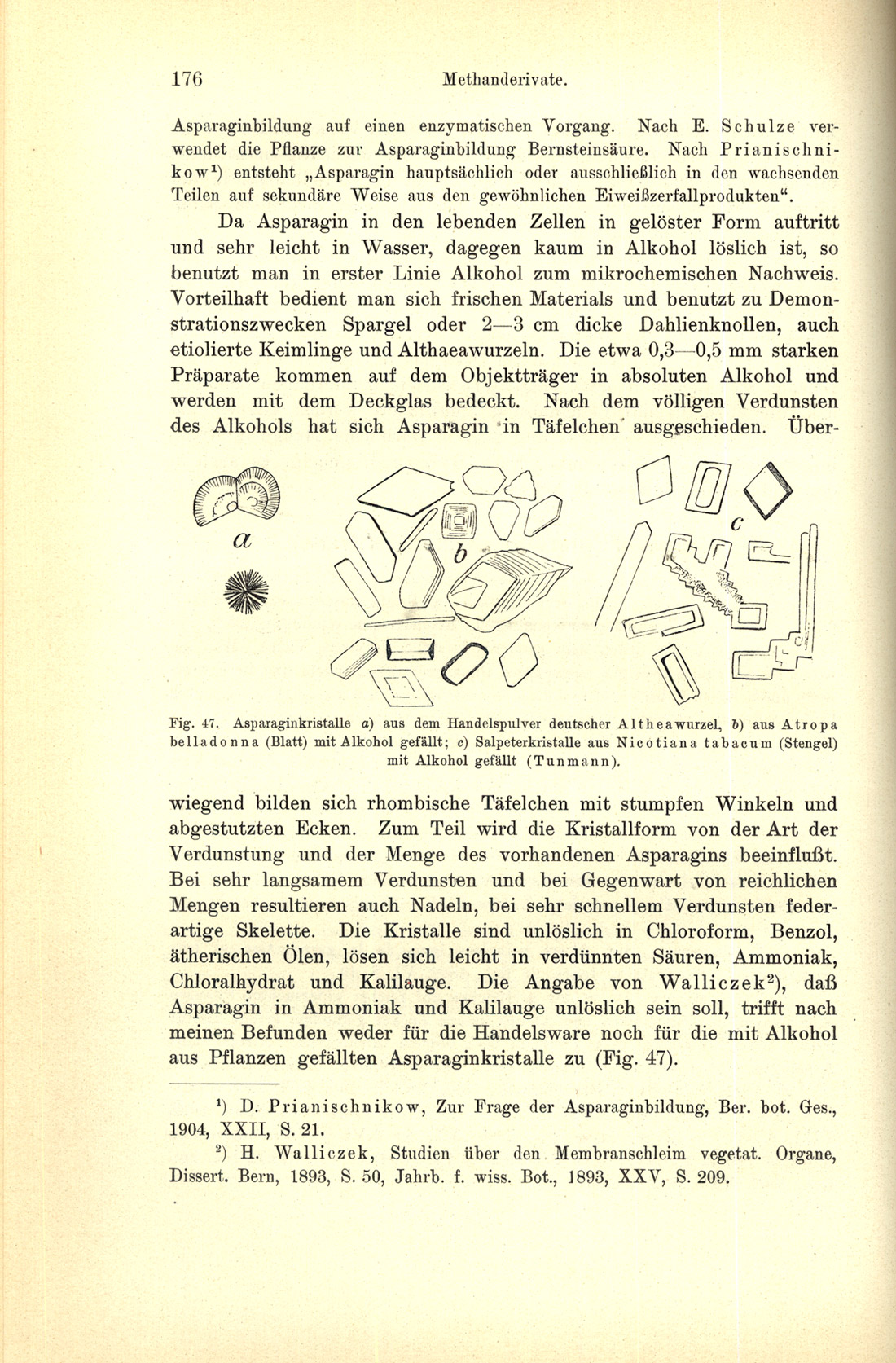

In the tradition started by Raspail almost 100 years earlier, Dr. O. Tunmann wrote a textbook in 1913 devoted to the application of microchemical tests to plant materials [Tunmann (1913)]. This text (Figure 23) on plant microchemistry contained 137 illustrations (Figure 24). A second edition updating the text was published in 1922.

MOLISCH

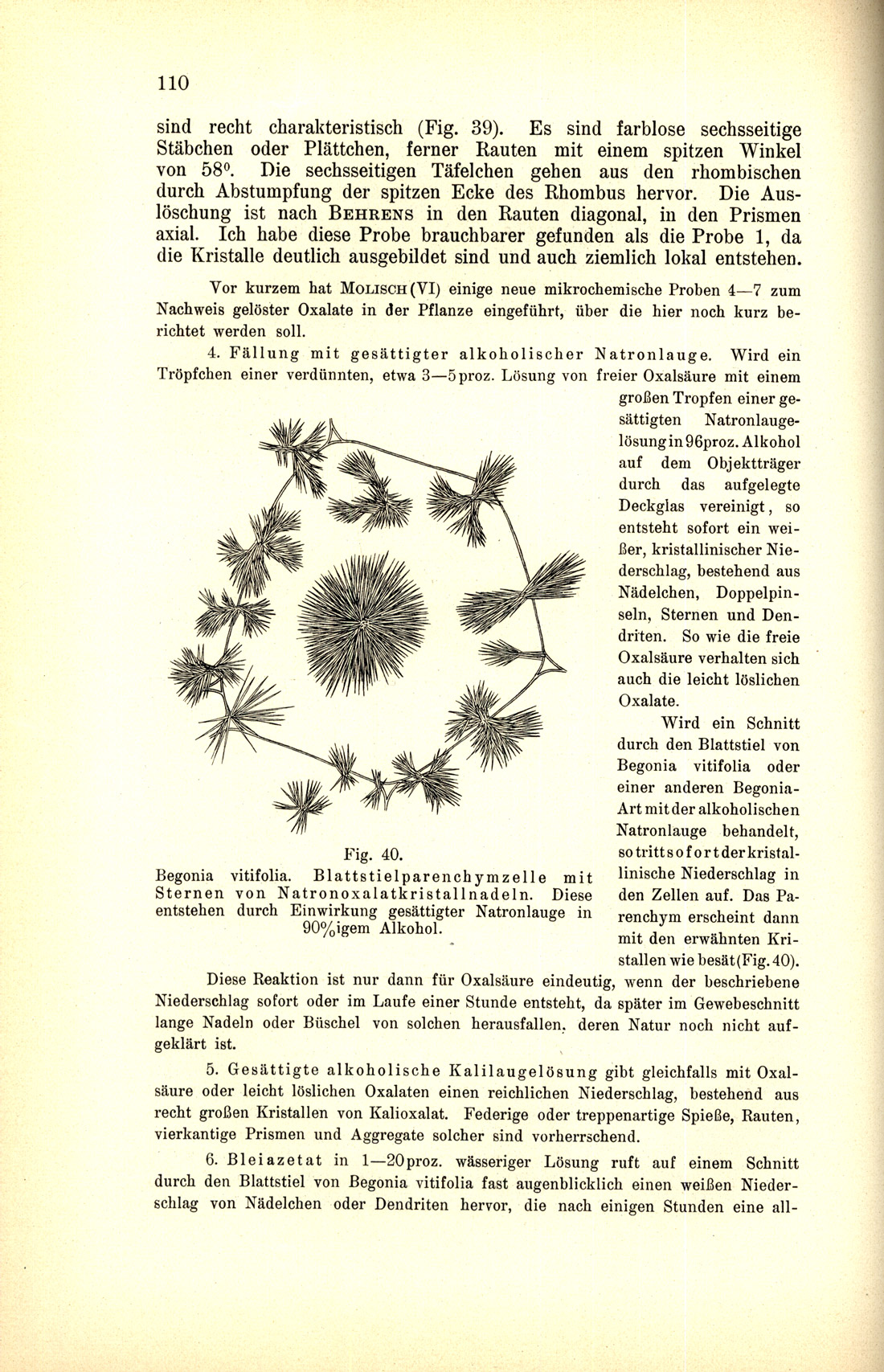

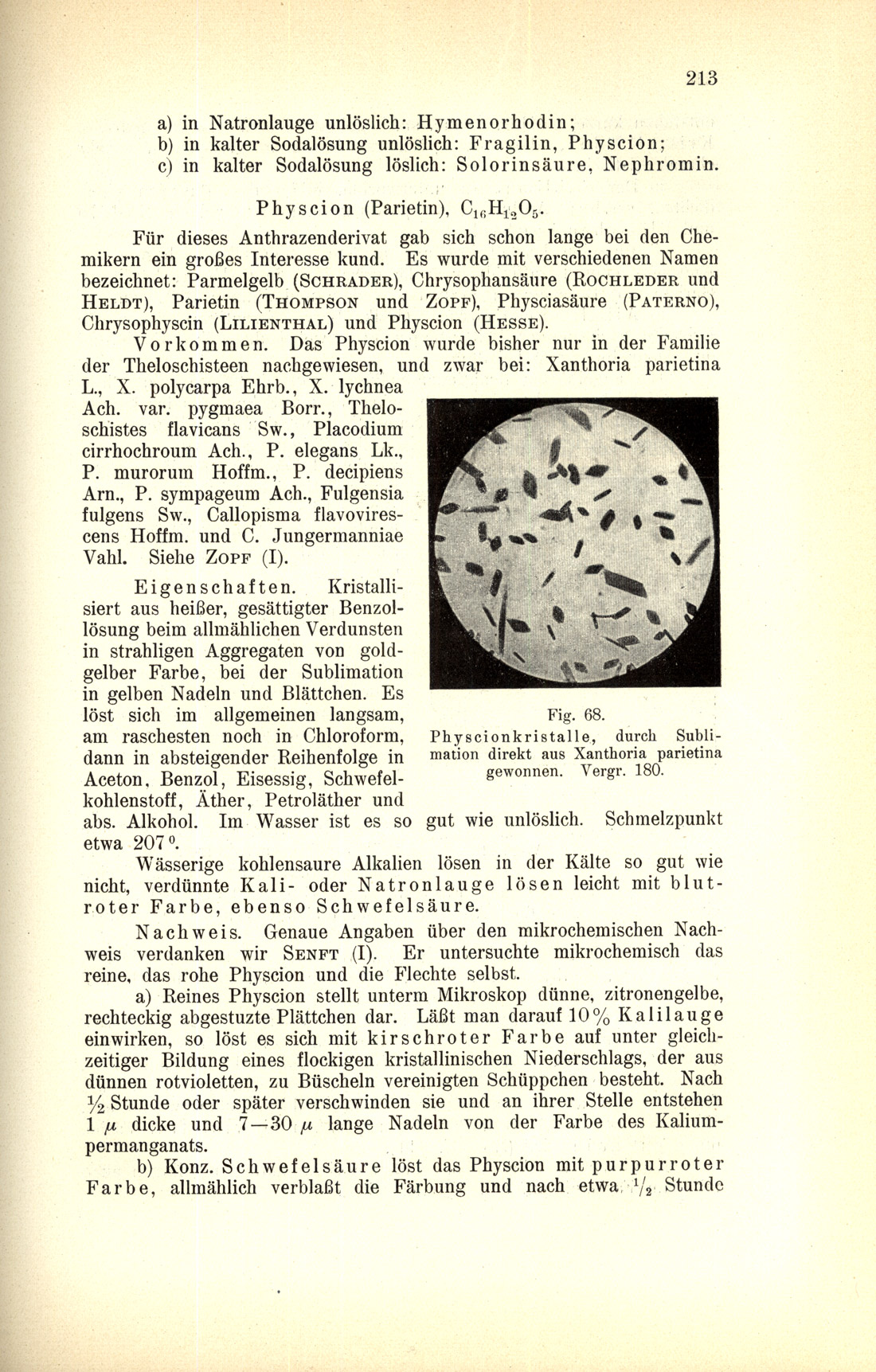

Also in the tradition started by Raspail and complementing Tunmann’s books on plant microchemistry, Hans Molisch published several books on plant structure and microchemistry, including the third edition of his Mikrochemie der Pflanze (1923). The third edition of this text (Figure 25) contained 135 text figures, including line drawings (Figure 26), and photomicrographs (Figure 27).

ÉMILE MONNIN CHAMOT

Émile Monnin Chamot (Figure 28), true to his promise to Professor Behrens, started teaching microchemical analysis immediately upon his return to Cornell. The first courses consisted of informal lectures, demonstrations, and laboratory practices. Students were guided by their notes and by mimeographed and typewritten sheets. Between 1899 and 1902, Chamot wrote about twenty articles on microchemical analysis for the Journal of Applied Microscopy. These articles, along with the laboratory direction sheets and lecture notes, became the nucleus for Chamot’s book, Elementary Chemical Microscopy [Chamot É.M. (1915)], published by Wiley in 1915. Many copies of this first textbook for American chemists bear the imprint year 1916, because within one year of its appearance, a third thousand had to be printed. Incidentally, in spite of Raspail’s introduction of the term “chemical microscopy,” Chamot is often credited with having coined the name in about 1914, because he realized that in addition to microchemical analysis, there were physical and physicochemical factors involved in chemical behavior, and then there were also the quantitative methods of Emich and Pregl being developed; these all applied to problems that chemists were called upon to investigate. In his 1915 Preface, Chamot acknowledges his indebtness to the then late Professor Behrens, and to Simon Henry Gage, Professor Emeritus of Histology and Embryology, also at Cornell, about whom Chamot says, “It is largely due to the spirit of optimism and love for research with which this indefatigable investigator is ever surrounded that the author was originally led to enter the field of applied microscopy when first a student.”

America then entered World War 1, and a partly rewritten and enlarged second edition [Chamot, É.M. (1921)], of Chamot’s book came out in 1921. In the Preface to the second edition, Chamot notes how the microscope had come to be regarded as a necessary adjunct to the chemical laboratory, and how it had been applied to problem solving during the war in more new applications than in the preceding quarter of a century. Here he also announces that a Handbook of Microscopic Qualitative Analysis is in preparation, and that it will include copious photomicrographic illustrations. Finally, he states his indebtedness to Simon Henry Gage, and to Clyde Walter Mason for helpful suggestions.

É.M. CHAMOT AND C. W. MASON

In 1930, volume 1 of the Handbook of Chemical Microscopy [Chamot, É.M. and C.W. Mason (1930)], by É M. Chamot and C. W. Mason was published by Wiley, with the announcement that Volume 2 was in preparation. This first volume is devoted to the Principles and Use of Microscopes and Accessories, and Physical Methods for the Study of Chemical Problems. Volume 2, on Chemical Methods and Inorganic Qualitative Analysis, came out the following year, 1931. Interestingly, the authors state in their Preface that “In spite of the continued growth which microscopical qualitative analysis has undergone, it is noteworthy that the methods of this branch of chemistry, as taught by Behrens in the early nineties, stand with little need for modification…. Building better than he knew, he chose reagents which are still unexcelled for convenience, rapidity, and versatility.”

After eight years of continued progress in chemical microscopy, and classroom observation, a second edition of the Handbook [Chamot, É.M. and C.W. Mason (1938 & 1940)], was deemed necessary. Accordingly, Volume 1 of the second edition was published in 1938, and Volume 2 in 1940.

Chamot retired in 1938, and died in 1950. Mason prepared a new (third) edition of Volume 1 only of the Handbook…. and Wiley published it in 1958 [Chamot, É.M. and C.W. Mason (1958)]. There is a Michel-Lévy chart in full color in this volume, and the footnote references number in the thousands.

Volume 2 of the Handbook …. went out of print in 1968, and was reprinted in 1989 by the McCrone Research Institute (Chicago), but is again no longer available.

In the years between 1940 and 1968, the Handbook…. was reprinted a number of times, sometimes in a smaller format, and always on different paper; variations in the paper are as common as in Winchell’s Elements of Optical Mineralogy. C.W. Mason again revised Volume 1 only as a fourth edition in 1983 [Mason C.W. (1983)]; Chamot’s name was dropped as co-author in this edition. Mason has since died.

Intriguingly, there exist notes prepared by Chamot for a proposed Volume 3 on the Identification of Organic Acids. The practical microscopist must have the second edition of Volume 2; the reprint is fine. Of Volume 1, my preference is for the third edition [Chamot, É.M. and C.W. Mason (1958)].

The 1920s

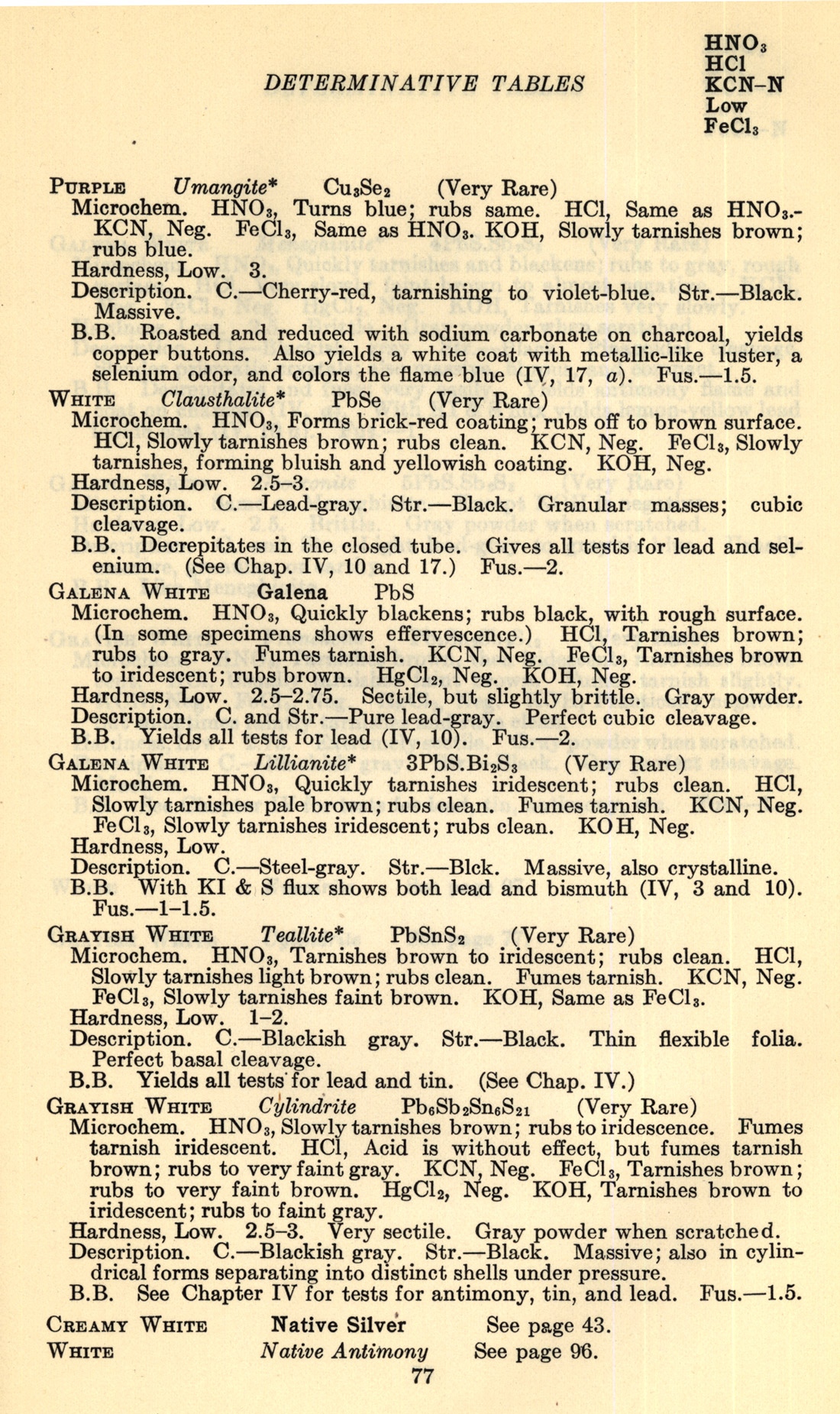

The decade opened with the publication of Davy and Farnham’s (1920) book on Microscopic Examination of the Ore Minerals. [Davy and Farnham (1920)]. What is uncommon about this book (Figure 29), is that it is thumb-indexed by microchemical reagent. Here (Figure 30) is a page from the Determinative Tables giving the reaction to HNO3, HCl, KCN-N, and FeCl3.

The 1920s saw the reissue of older books, such as the second edition of Chamot’s Elementary Chemical Microscopy [Chamot, É.M. (1921)], but there were several new books of some interest. The first one that comes to mind is Some Microchemical Tests for Alkaloids [Stephenson, Charles H. (1921)], by Stephenson and Parker. At the back of this book are 26 plates, each with six photomicrographs illustrating the microcrystal tests for the alkaloids. There is also a fold-out Table of Microchemical Reactions of 51 Alkaloids With 35 Reagents, which is still being used in current drug identification courses. Other useful features of this book include a Table Showing Best Tests for Each Alkaloid, and a Scheme for 21 Identification of Alkaloids.

In 1922, Chamot reported on microscopical researches involving problems with small arms ammunition primers that were coincident with the entrance of the United States into World War I. Small arms ammunition, especially .30 caliber cartridges intended for field and aircraft machine-guns, was characterized by a disturbingly high number of misfires traceable to the primers. Mercury fulminate had been used in some compositions, and azides were being considered; the “souring” of some primers was ultimately attributed to bromate contamination creating a chemical reaction in potassium chlorate priming mixtures. At any rate, Chamot reported on his researches in a now scarce booklet, The Microscopy of Small Arms Primers [Chamot, É.M. (1922)].

In 1923, Fritz Pregl (1860-1930), who earned an M.D. degree at the University of Graz in 1894, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His work is traceable back to 1909, when he visited Emich’s laboratory in Salzburg, and heard him lecture on micro methods. This inspired him to develop a variety of quantitative micro methods.

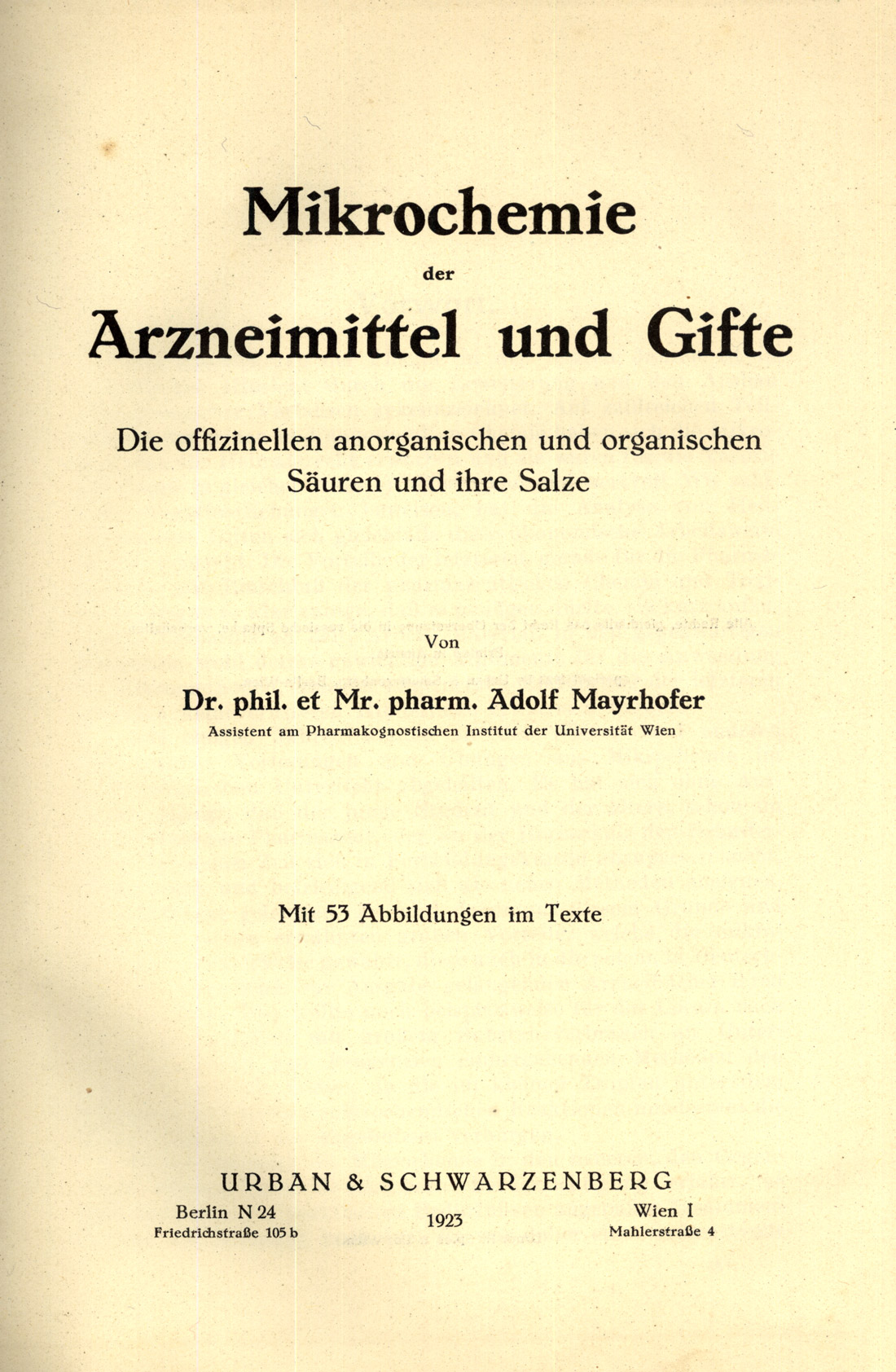

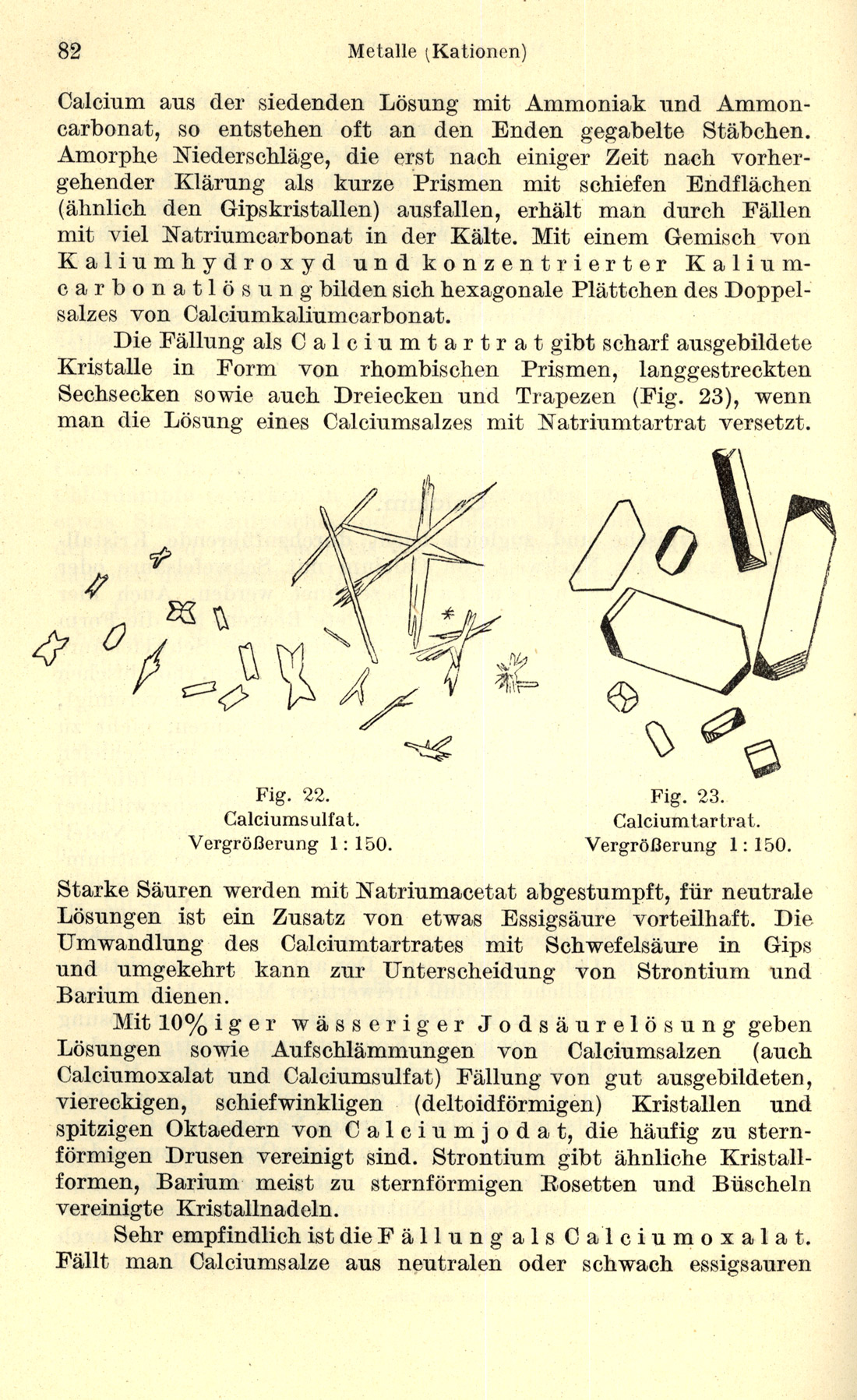

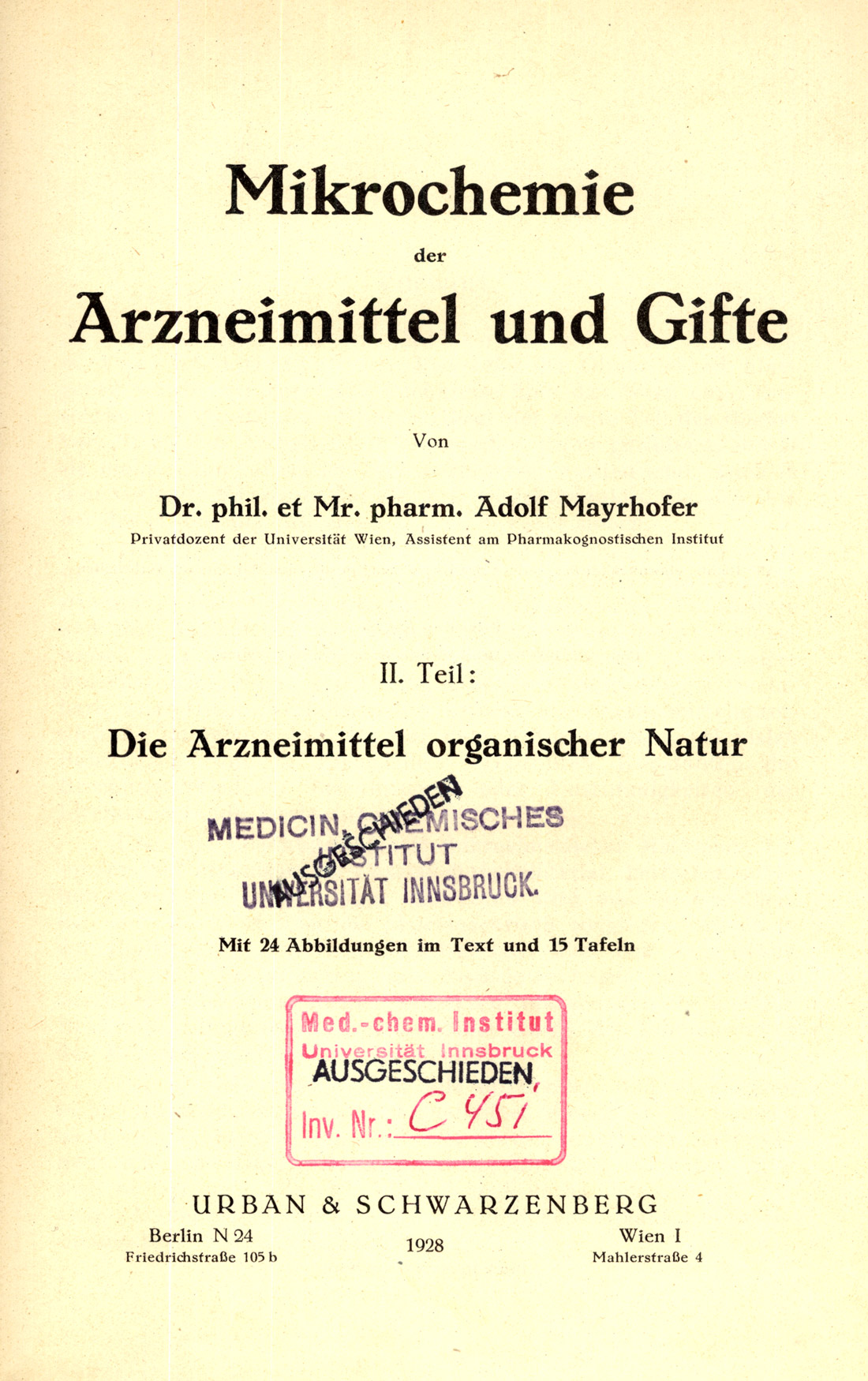

1923 was also the year that saw the publication of the first edition (Figure 31) of Mayrhofer’s Mikrochemie der Arzneimittel und Gifte [Mayrhofer (1923)]; the microchemical reactions are illustrated with line drawings (Figure 32). Part 2 of this work on the microchemistry of pharmaceuticals and poisons (Figure 33) was published in 1928. Part 1 deals with the microchemistry of the “official” inorganic and organic acids and their salts, and Part 2 is devoted to the microchemical analysis (Figure 34) of organic pharmaceuticals.

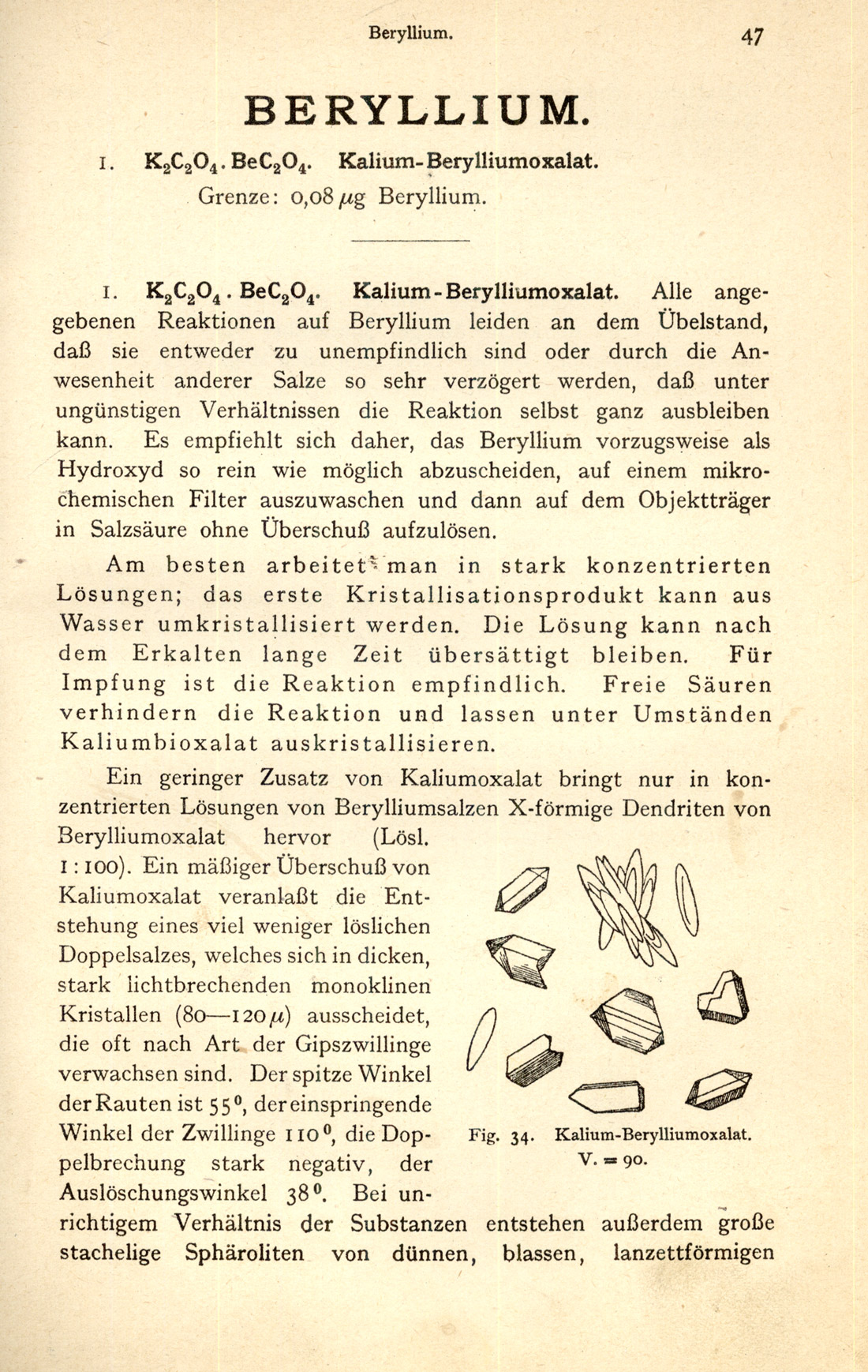

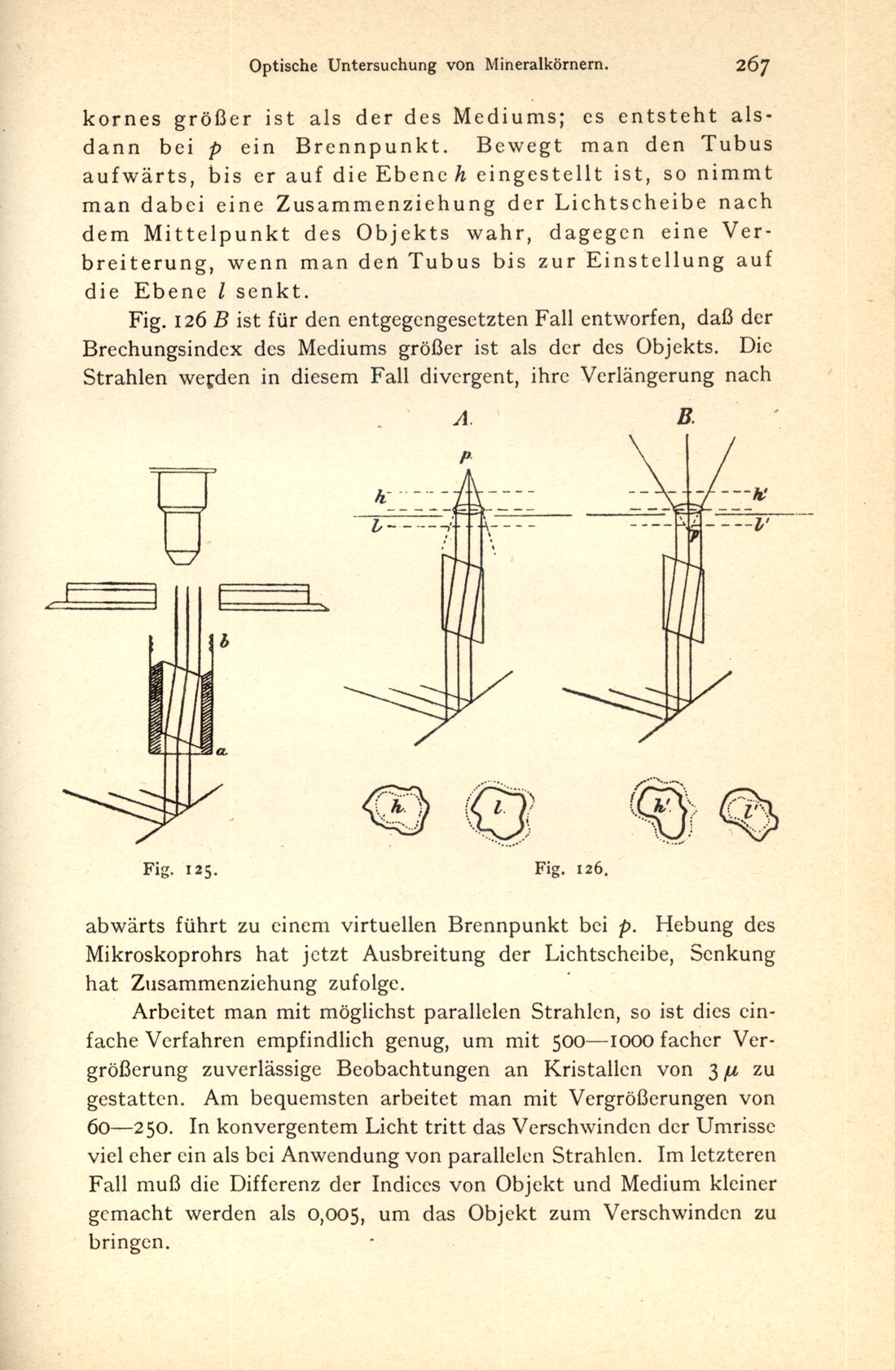

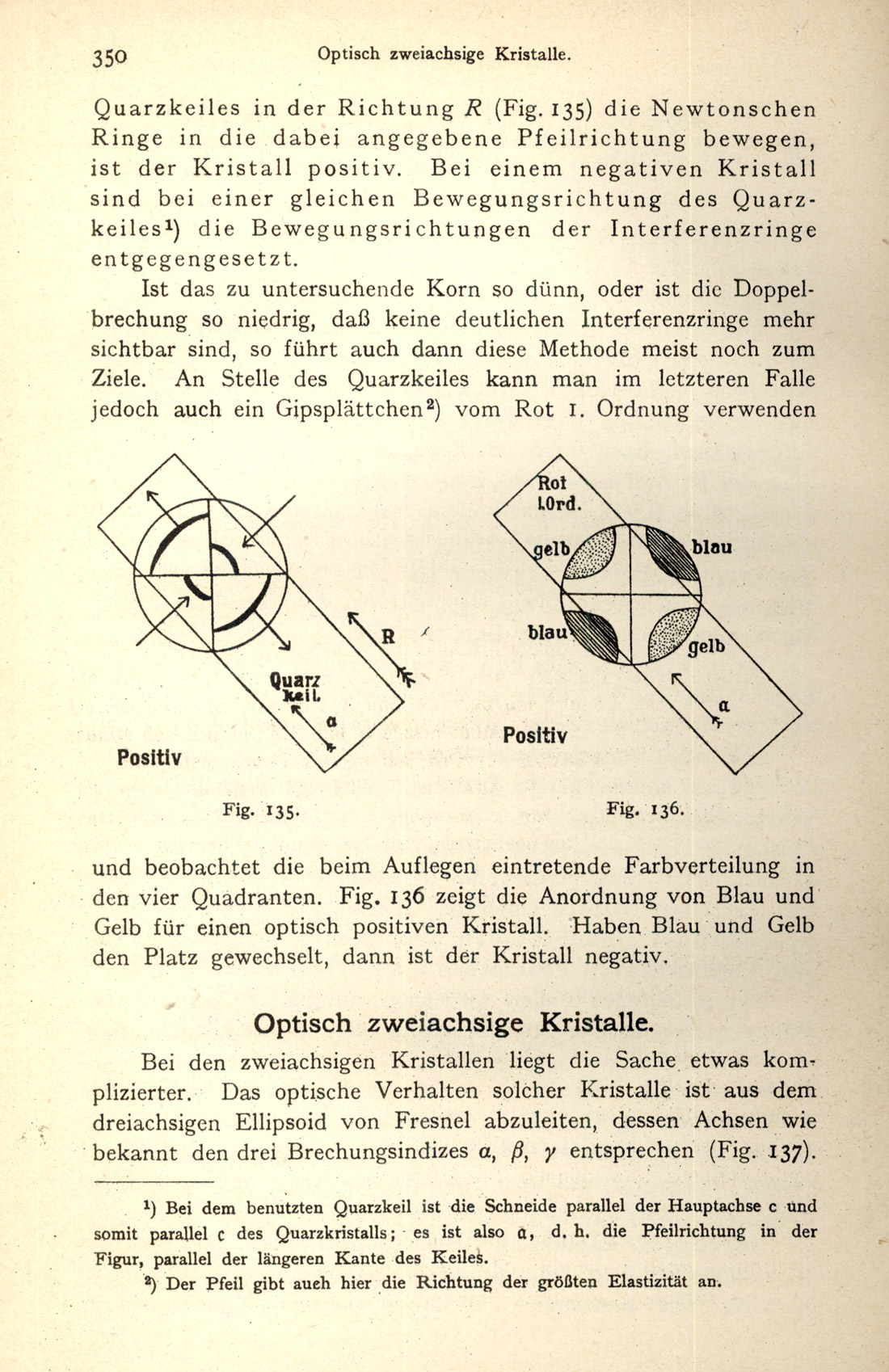

In 1921, the third edition of Kley’s earlier Behrens-Kley Mikrochemische Analyse was published [Kley, P.D.C. (1921)]. This edition Figure 35) contains 146 text figures, illustrating not only microchemical reactions (Figure 36), but discussions on the optical investigation of mineral grains (Figure 37), use of compensators (Figure 38), etc.

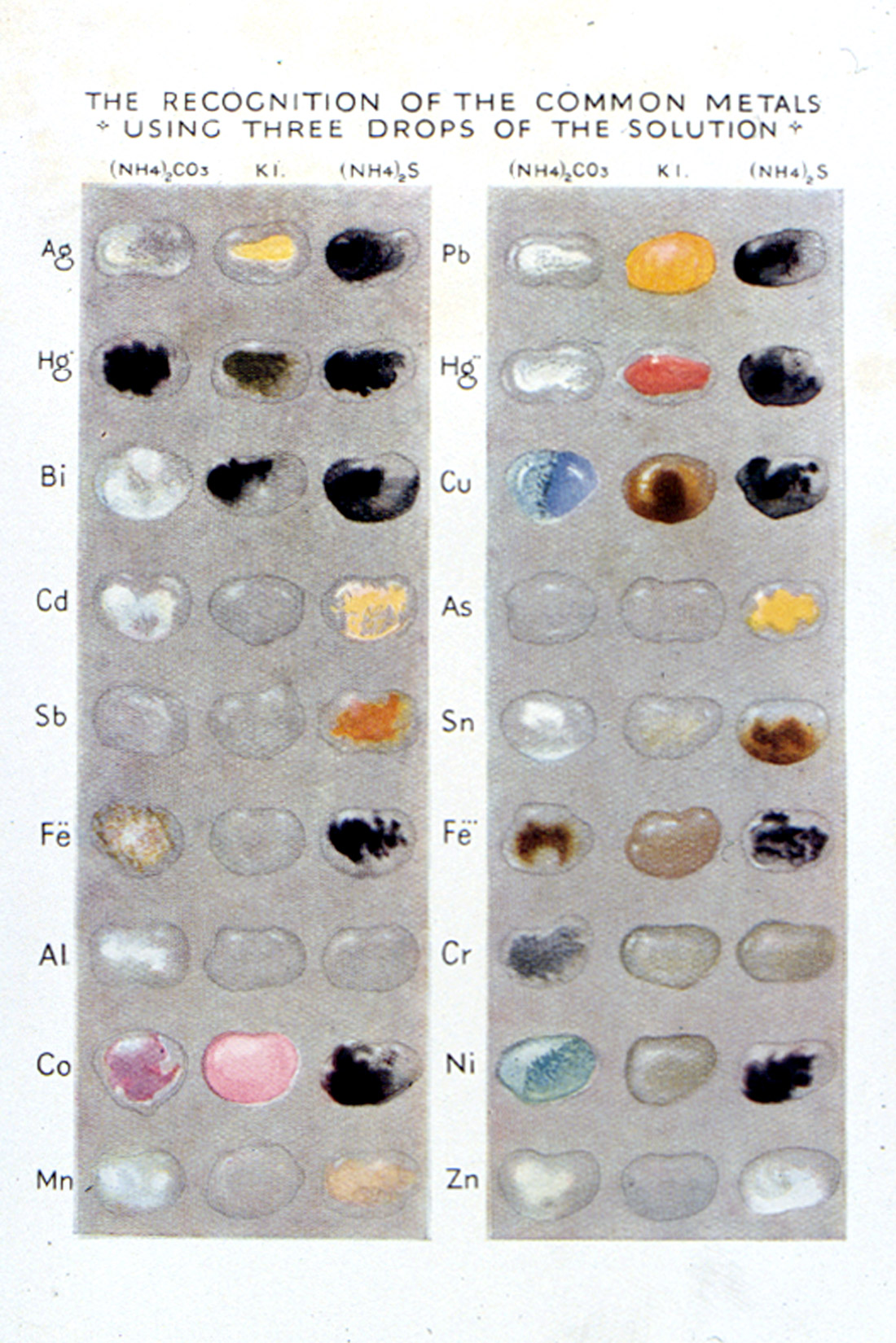

In 1925, Heffer published a charming little book called, Practical Chemistry by Micro-Methods [Grey, Egerton C.(1925)], written by Egerton C. Grey, Professor of Chemistry at the Government Medical School in Cairo. The frontispiece (Figure 39) consists of a photograph of a Student Examining the Effect of Mixing Two Drops. Reference is made to a color plate (Figure 40), which shows the reaction of eighteen different common metal ions using three different reagents (ammonium carbonate, potassium iodide, and ammonium sulfide). The book was intended for schools or for the earlier part of a university course, so as “to give the student a taste for this fascinating subject.”

Joseph B. Niederl took courses with Emich and Pregl, and then started teaching quantitative organic microanalysis at New York University in 1925.

The entire subject of quantitative microanalysis requires a survey all of its own. Some highlights, however, must include Pregl’s Quantitative Organic Microanalysis [Pregl, Fritz 1924)], translated by Fyleman; the Julius Grant books (five editions) Quantitative Organic Microanalysis, Based on the Methods of Fritz Pregl [Grant Julius (1924, 1930, 1951)], Niederl’s text, Micromethods of Quantitative Organic Elementary Analysis [Niederl, J.B. and V. Niederl (1938)], Paul Kirk’s Quantitative Ultramicroanalysis [Kirk, Paul L. (1950)], and Korenman’s Introduction to Quantitative Ultramicroanalysis [Korenman, I.M. (1965)].

ROSENTHALER

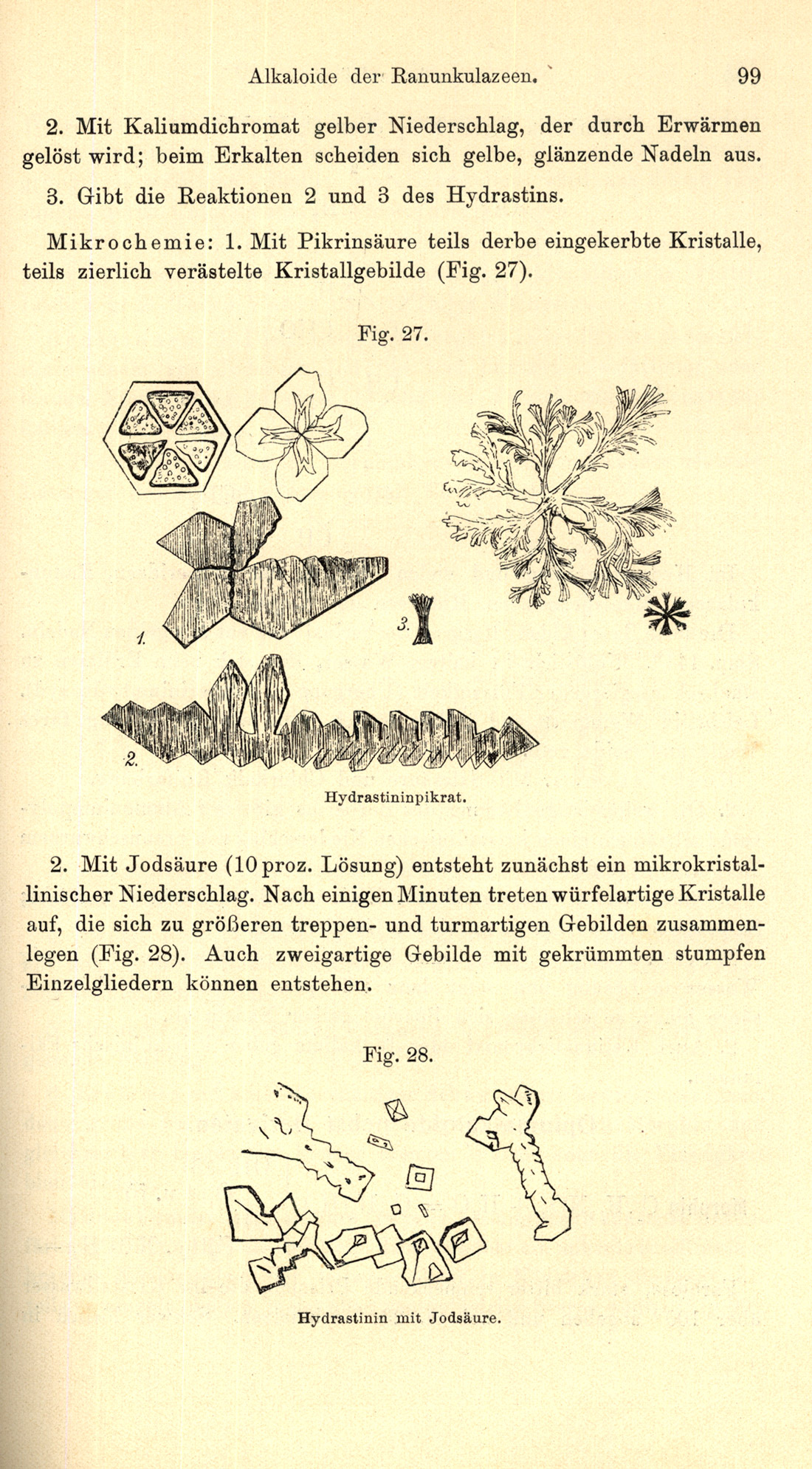

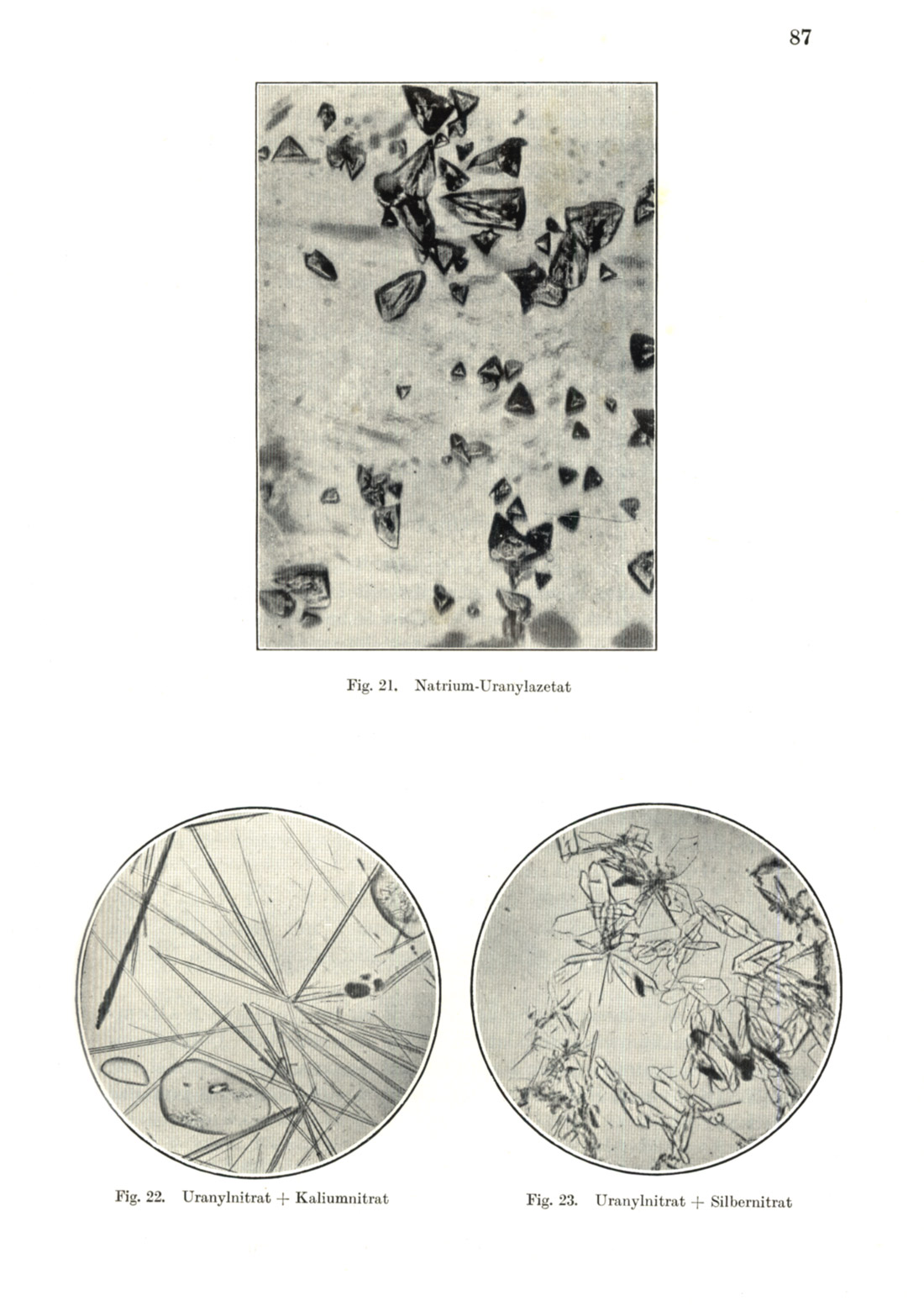

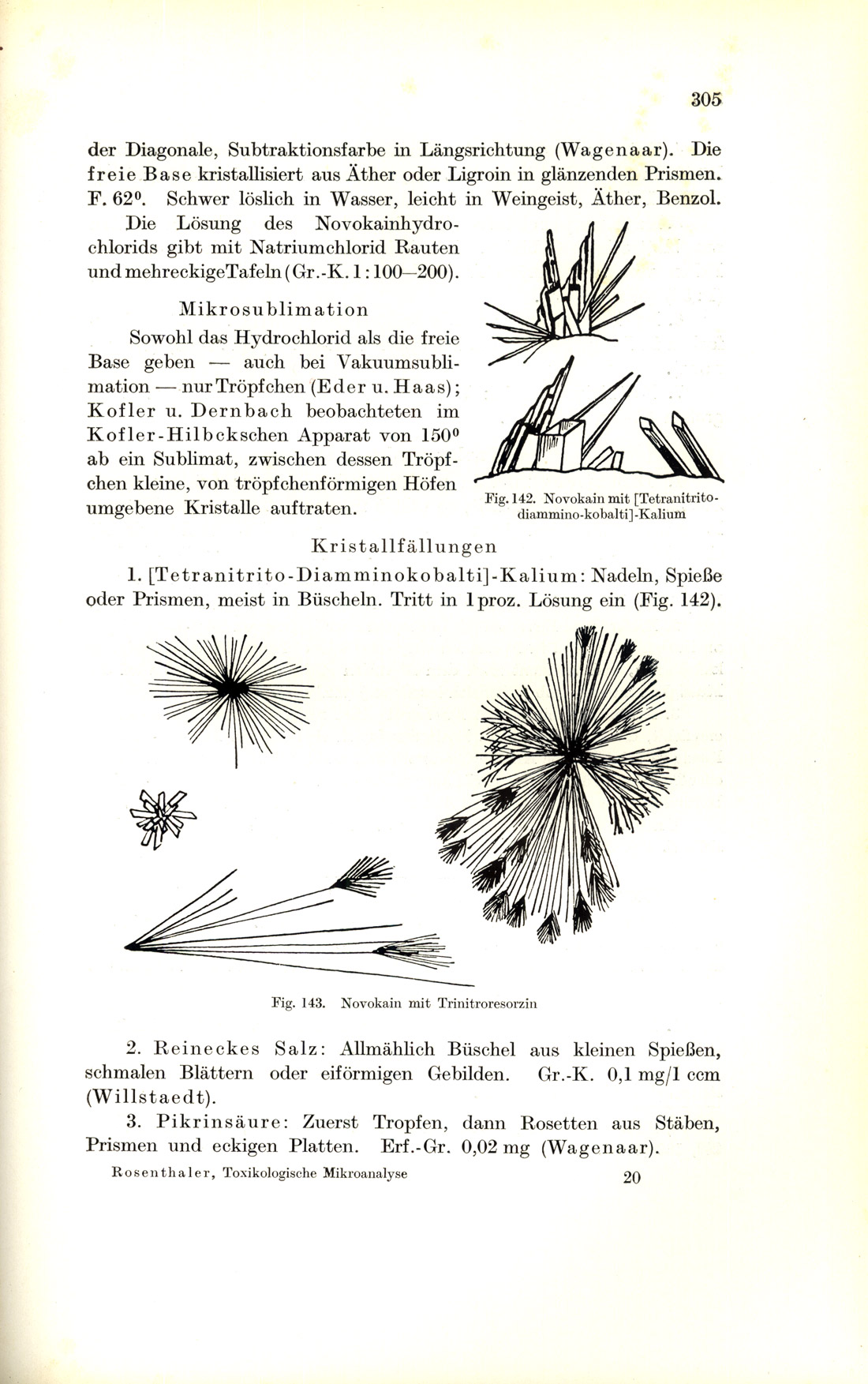

Dr. Leopold Rosenthaler, Professor at the University of Bern, Switzerland, wrote several books of interest to the microchemist, during the 1920s and 1930s. His Grundzüge der chemischen Pflanzenuntersuchung, which is devoted to the chemical investigation of plants, went through three German editions. The third edition [Rosenthaler (1928)], which followed the second by five years, was translated into English in 1930 as, The Chemical Investigation of Plants by Sudhamoy Ghosh, Professor of Chemistry, School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Calcutta [Rosenthaler/Ghosh (1930)]. Not all of the chemical tests are microscopical, and there are very few illustrations. Rosenthaler’s 1922 book, Qualitative Pharmazeutische Analyse [Rosenthaler (1922)] (Figure 41) is a textbook devoted to the analysis of pharmaceuticals for students of pharmacy and dispensing chemists (Figure 41). Line drawings (Figure 42) illustrate the microchemical tests. His 1935 book Toxikologische Mikroanalyse [Rosenthaler (1935)] (Figure 43); deals with the qualitative microchemical analysis of poisons and other materials of importance to the medico-legal chemist. The 173 text figures include both photomicrographs (Figure 44) and line drawings (Figure 45).

The 1930s

Again, there is considerable overlap when taking a decades approach, because of updates of older books and because of the historical links between those writing the books. Still, some very important new books in the field were first published in the 1930s.

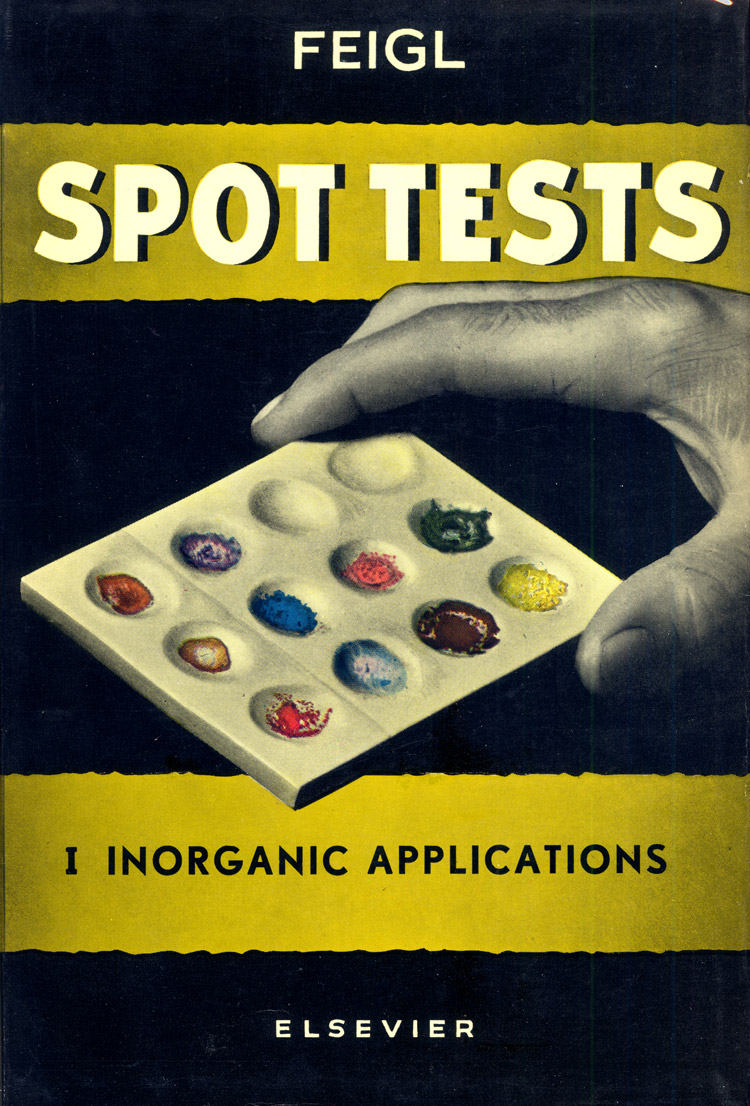

Fritz Feigl is an important name here. His Qualitative Analyse mit Hilfe von Tupfelreaktionen [Feigl, Fritz (1931)]; published in 1931 is only one of this prolific writer’s books. The second English edition, Qualitative Analysis by Spot Tests [Feigl (1939)], translated from the Third German edition, was published in 1939 (Figure 46). Another is his Chemistry of Specific, Selective and Sensitive Reactions [Feigl, Fritz (1949)], published in 1949 (Figure 47). The more generally available, and highly recommended, books of his are the two spot test books, Spot Tests in Inorganic Analysis [Feigl, Fritz and Vinzenz Anger (1937, 1939, 1946, 1954, 1958)], and Spot Tests in Organic Analysis [Feigl, Fritz (1937, 1954, 1956, 1960)]. Here are the attractive front covers of the 1954 fourth edition (Figure 48, Figure 49). I like these two books very much; they are not strictly microscopical tests; they are intended, as the titles suggest, to be conducted in spot plates; they are colorimetric/filter paper/spot plate tests. Many of the described reaction products are deeply colored, and I have, on more than one occasion, successfully adapted the tests to microscopic scale, especially when my unknown was organic. I, personally, would not be without these two books close at hand. All of the editions going back to the 1937 translation are useful, but the latest editions have been completely revised and enlarged.

In 1932, Emich’s Microchemical Laboratory Manual [Emich, Friedrich (1932)], with a section on Spot Analysis by Fritz Feigl, was translated into English by Frank Schneider, and was published by Wiley. Schneider was working in the microchemical field for a few years with A.A. Benedetti-Pichler, who was Emich’s former assistant and co-worker. The American edition of Emich’s book was translated, partly, as a tribute to “that grand old master of microchemistry.”

A.A. Benedetti-Pichler had been Privat Dozent at the Technische Hochschule in Graz, Austria; he and W.F. Spikes had both been Emich’s students. Together, Benedetti-Pichler and Spikes wrote, Introduction to the Microtechnique of Inorganic Qualitative Analysis [Benedetti-Pichler, A.A. and W.F. Spikes (1935)], in 1935, and dedicated the volume to Emich. One of the features of this book is the use of empty 3-inch diameter circles throughout, in which the user is expected to draw the microscopical view of the crystals or reaction product being discussed. In 1942, this book was replaced by, Introduction to the Microtechnique of Inorganic Analysis [Benedetti-Pichler, A.A. (1942 and 1950)], under the authorship of Benedetti-Pichler alone. The 3-inch diameter circles for do-it-yourself drawing are not in this version.

Hotstage methods (fusion methods; thermomicroscopy) is another category which requires a separate survey; however, a few works may be mentioned here. The techniques are trace-able back to Otto Lehmann’s works in the 1880s and after. (I regard myself as extremely fortunate to have one of Lehmann’s books, Die scheinbar lebenden Kristalle, that bears the library stamps of the Technische Hoogeschule in Delft where Behrens taught).

In 1936, Kofler, Kofler, and Mayrhofer saw the publication of their Mikroskopische Methoden in der Mikrochemie [Kofler, L., A. Kofler and Mayrhofer, A. (1936)], Mayrhofer had previously (1923) published his Mikrochemie der Arzneimittel and Gifte [Mayrhofer, A. (1923)], Kofler and Kofler had their Thermomikromethoden [Kofler L., and A. Kofler (1954)], published in 1954. And then Maria Kuhnert-Brandstatter, Professor of Pharmacognosy, University of Innsbruck, and close friend and colleague of the Koflers, saw her highly valuable Thermomicroscopy in the Analysis of Pharmaceuticals [Kuhnert-Brandstätter, Maria (1971)], published in 1971. Her book is dedicated to Adelheid Kofler, widow of her highly esteemed teacher, Ludwig Kofler.

Walter McCrone used to tell the story that, both he and the Koflers were, unknown to each other, developing thermal methods for the study of fusible compounds, and neither knew that Otto Lehmann had already developed most of their procedures in the 1880s [Lehmann, Otto (1891)], McCrone published his work Fusion Methods in Chemical Microscopy [McCrone, W.C. (1956)], incorporating the Koflers’ analytical tables in 1956.

In 1938, a little book appeared that was intended to introduce senior chemistry students to the methods of microchemistry; it was Cecil L. Wilson’s An Introduction to Microchemical Methods [Wilson, Cecil L. (1938)]. This book also introduces the student to the tintometer, the calorimeter, the nephelometer, and the spectrograph, in addition to qualitative organic and inorganic analysis.

The 1940s

Most of the books written during the World War II years were published after the war. Belcher and Wilson authored Qualitative Inorganic Microanalysis [Belcher, R. and C.L. Wilson (1946)], in 1946. Ten years later the second edition came out under the title, Inorganic Microanalysis; Qualitative and Quantitative [Belcher, R. and C.L. Wilson (1957)]. Many of the Emich-Schneider/Benedetti-Pichler/Chamot and Mason techniques and apparatus are utilized here.

The year 1946 also saw the first edition of Frank L. Schneider’s Organic Qualitative Analysis [Schneider, F.L. (1946)], which we will see again in 1964 as the much enlarged, Qualitative Organic Microanalysis [Schneider, Frank L. (1964)].

The book, Reagents for Qualitative Inorganic Analysis (1948) reports on new analytical reactions and reagents. (Figure 50).

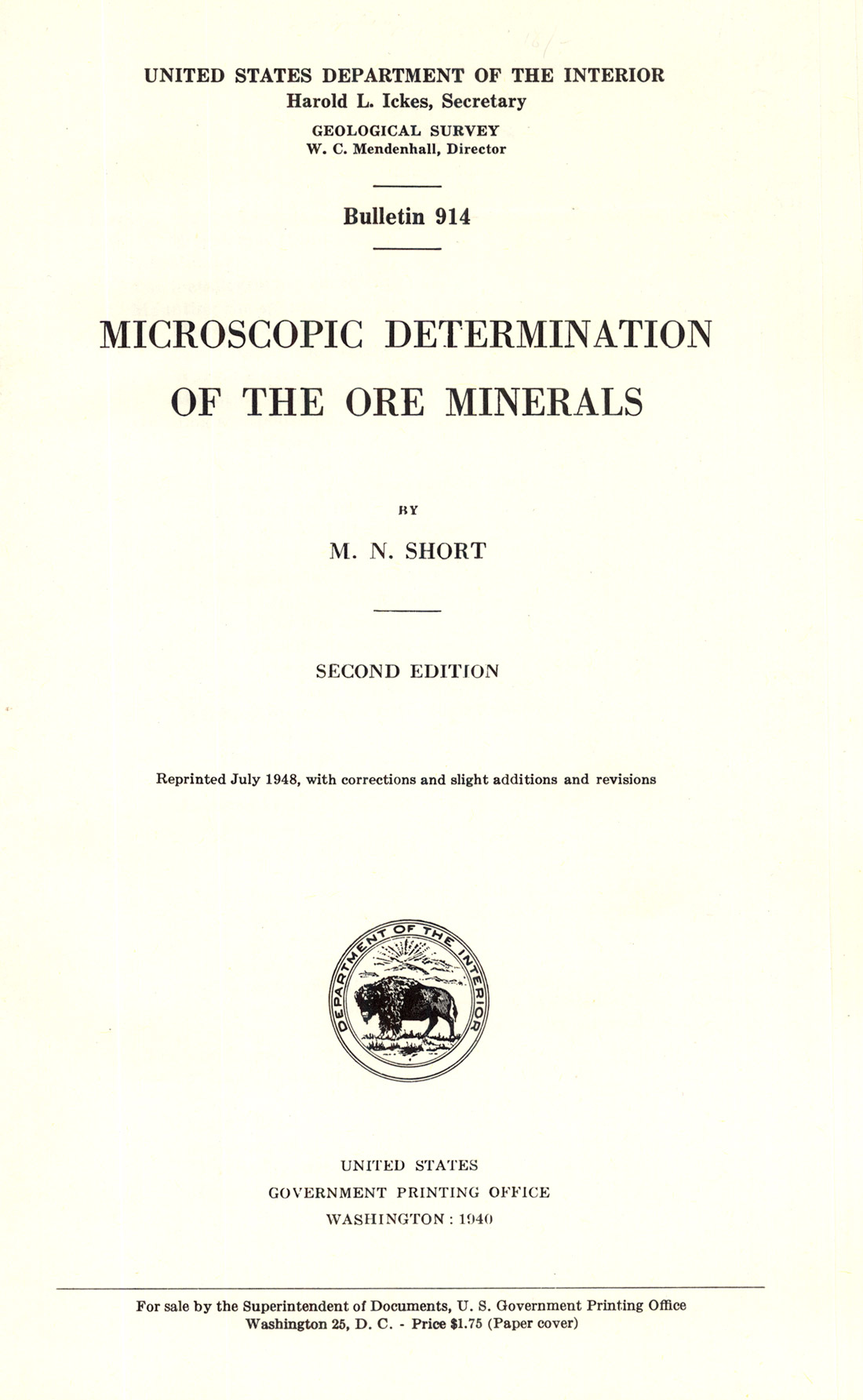

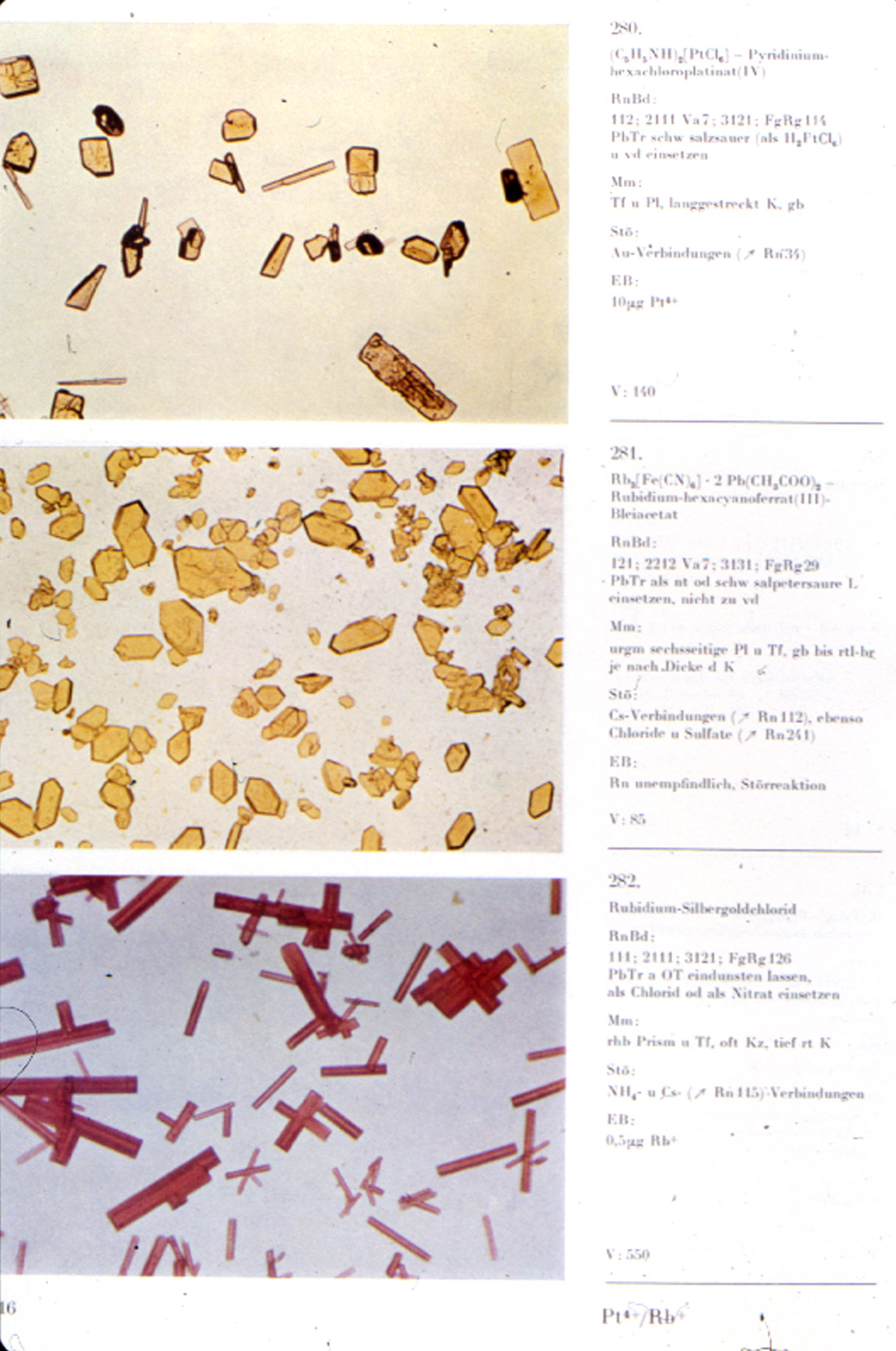

M.N. Short’s book on the Microscopic Determination of the Ore Minerals (Figure 51), published in the previous decade, came out as a second edition in 1940 [Short (1940)]. This volume contains a section on microchemical methods, and Figure 52 is one of the color photomicrographs illustrating a microchemical test for silver.

Also in 1948, Kofler and Kofler’s Mikromethoden zur Kennzeichnung organischer Stoffe and Stoffgemische [Kofler, L. and Adelheid Kofler (1948)], was issued. An English translation of this book was made by McCrone in 1952, and was, at one time, available from the McCrone Research Institute.

The 1950s

In 1950 there was a second printing of Benedetti-Pichler’s Introduction to the Microtechnique of Inorganic Analysis [Benedetti-Pichler, A.A. (1942 and1950)]. In 1954 there appeared another edition of Feigl’s Spot Tests… [Feigl, Fritz and Vinzenz Anger (1937, 1939, 1946, 1954, 1958)], [Feigl, Fritz (1937, 1939, 1946, 1954, 1956, 1960)], Maljaroff’s Qualitative anorganische Mikroanalyse [Maljaroff, K.L. (1953 and 1954)], first published in 1953, went into a second edition the following year.

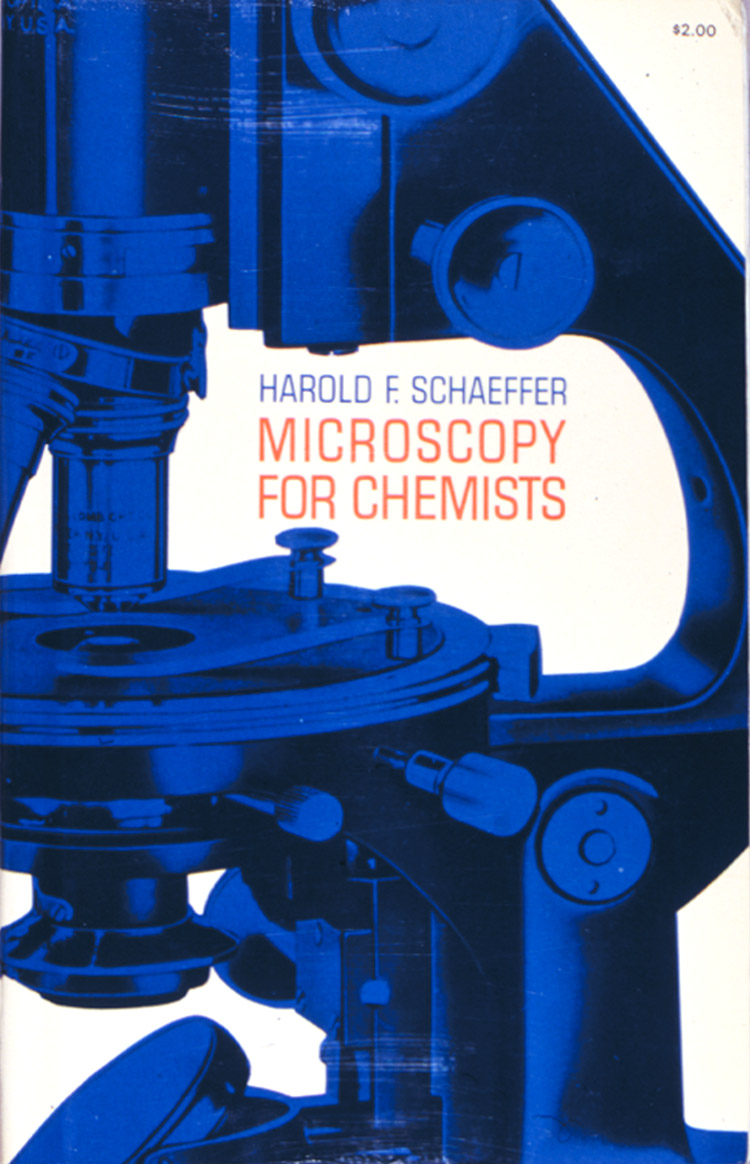

Harold F. Schaeffer’s very popular Microscopy For Chemists [Schaeffer, Harold F. (1953)], was published in 1953. It is a splendid book that went out of print, but demand for it remained sufficiently high, and Dover reprinted it. And now the Dover reprint (Figure 53) is no longer available. The experiments in this book make it an excellent teach-yourself choice.

Alimarin and Archangelskaja’s Qualitative Halbmikroanalyse [Alimarin, I.P. and W.N. Archangelskaja (1956)], was published in 1956.

And in 1958 Malissa and Benedetti-Pichler’s Anorganische qualitative Mikroanalyse [Malissa, H. and A.A. Benedetti-Pichler (1958)], was published.

The 1960s

There were two books published in 1960 of interest to microanalysts: The third edition of Geilmann’s Bilder zur qualitativen Mikroanalyse….[Geilmann, W. (1934, 1954, 1960)], and Alimarin and Petrikova’s Inorganic Ultramicro Analysis [Alimarin, I.P. and M.N. Petrokova (1960)]. Geilmann’s atlas has 403 figures (photomicrographs) in 52 plates. The book is very economical of space, and one of the many nice features is that the sensitivity in micrograms is given for almost all of the microcrystal tests. The quality of the black-and-white illustrations is excellent.

The first edition of Weisz’s Microanalysis by the Ring-oven Technique [Weisz, Herbert (1961 and 1970)], was published in 1961; the second edition appeared in 1970 (Figure 54). Fritz Feigl, who wrote the Foreword for the second edition, first learned of Weisz’s approach after World War II, and saw the first simple model of the ring oven shortly thereafter; he regards the method as an important milestone in spot test analysis.

One of my all-time favorite books was published in 1964: A.A. Benedetti-Pichler’s Identification of Materials via Physical Properties, Chemical Tests, and Microscopy [Benedetti-Pichler, A.A. (1964)]. This book “deals with the investigation of things as they are without any limitations as to the scope. It emphasizes the identification of materials – inorganic, organic, organized (biological), common, rare, described or not described in the accessible literature – as they actually occur in nature and industry, or are met in the investigation of mishaps and crime.” I love the bold inclusiveness of it all – everything, regardless of nature or origin. When he wrote this book and it’s Preface in 1963, Dr. A. A. Benedetti-Pichler was already retired Professor of Chemistry at Queens College, New York. He was born in Austria and educated at the Polytechnic Institute at Graz. He taught there until 1929, and then came to the United States and joined the faculty of New York University. He was active in organizing the Division of Analytical Chemistry of the American Chemical Society, and was also the founder of the American Microchemical Society. He had received the Pregl Prize of the Vienna Academy of Science in 1933, and the Emich Plaque of the Austrian Microchemical Society in 1955. How fortunate we are that he finished this book. It was published in 1964, and he died on December 10th of that same year.

In 1967, Hans Keune produced his beautiful atlas of microchemical tests, which is laid out in the same way that The Particle Atlas is. His book (Figure 55), Bilderatlas zur qualitativen anorganischen Mikroanalyse [Keune, Hans (1967)], is highly illustrated with photo-micrographs in black-and-white and color (Figure 56). All of the reagents and procedures are coded, and it is awkward to use at first, but usage brings familiarity with the abbreviations. The sensitivity limits are given for each microchemical test. This is a beautiful and very useful book, which is now difficult to obtain.

Charles C. Fulton’s Modern Microcrystal Tests for Drugs [Fulton, Charles C. (1969)], was published in 1969, and is still a standard reference work in drug identification. All of the modern schemes incorporate Fulton’s tests.

RECENT BOOKS

A relatively recent book to be published in the spot test tradition is the second edition of Ervin Jungreis’ Spot Test Analysis [Jungreis, Ervin (1984 and 1997)]. It continues the tradition of providing quick, inexpensive, definitive tests for clinical, environmental, forensic, and geochemical applications.

More recently, Andrew Holmes’ (2002) Rapid Spot Testing of Metals, Alloys and Coatings (Figure 57) was reviewed.

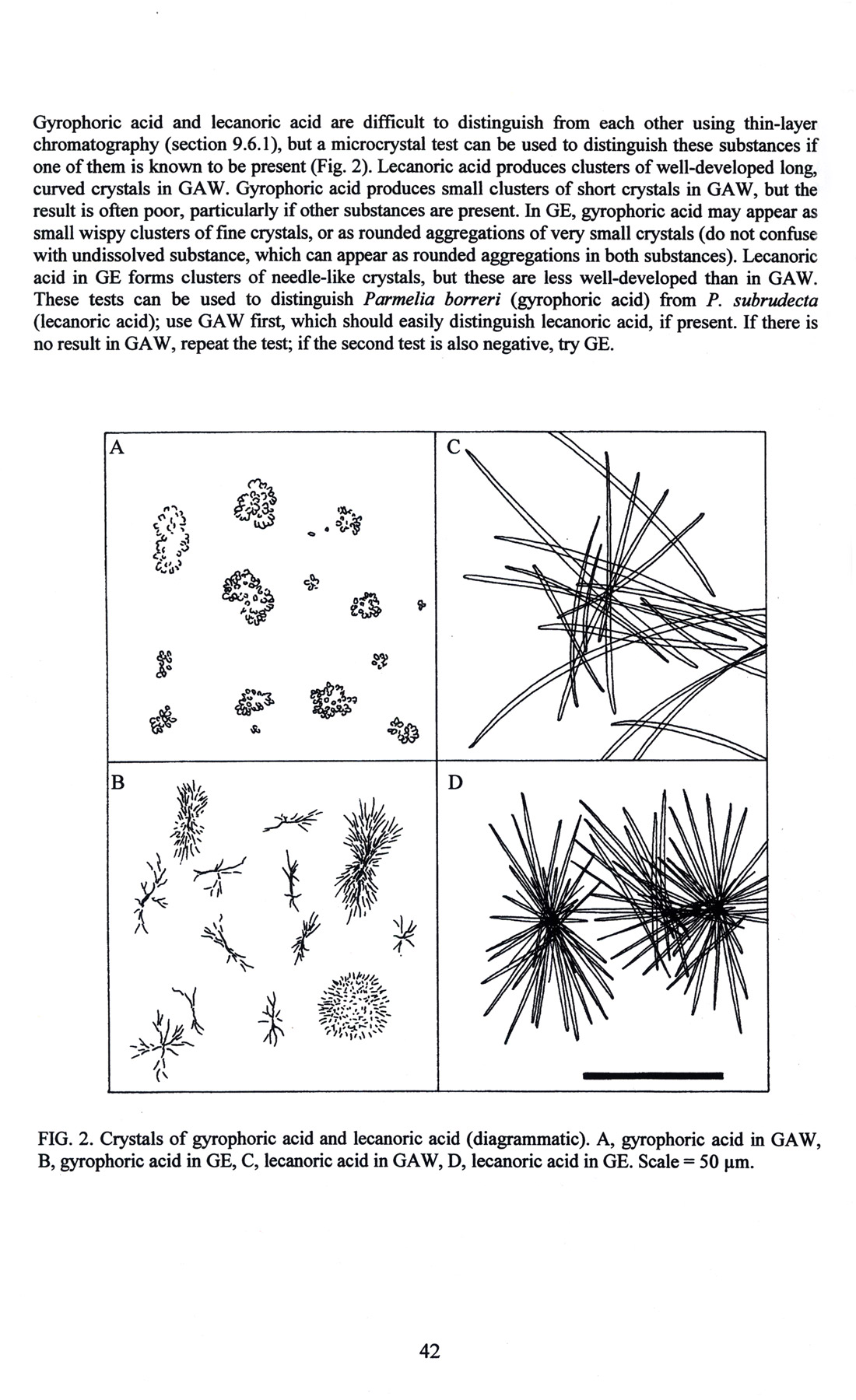

A highly specialized application of microchemistry is for the identification of lichens (Figure 58 and Figure 59), [Orange, et alii (2001)].

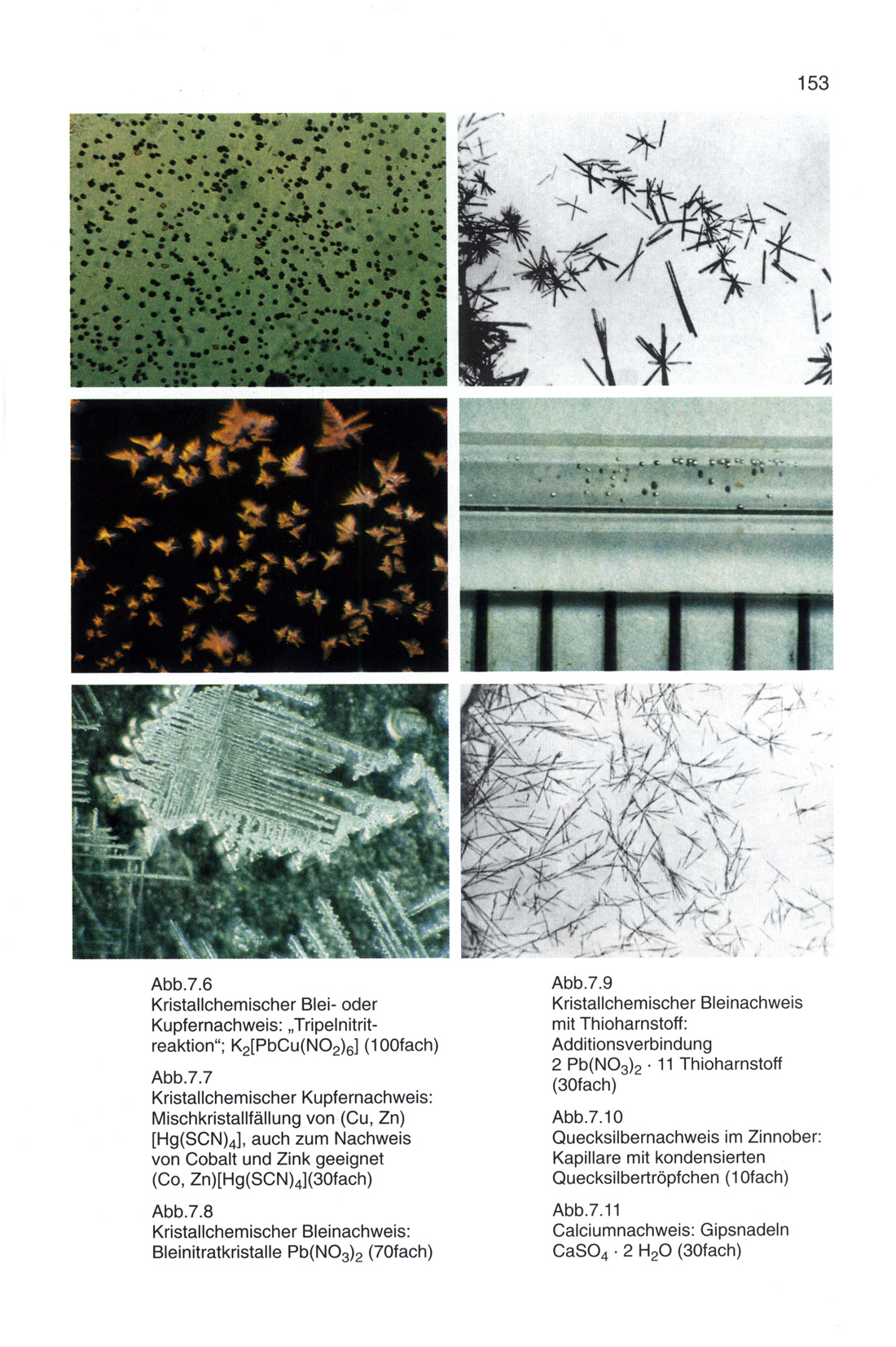

Another specialized application is that for the identification of historical painter’s materials, as we have in Schramm and Hering’s (1988) Historische Malmaterialien (Figure 60 and Figure 61).

Volume X of Wilson and Wilson’s (1980) Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry is devoted to organic spot test analysis. (Figure 62)

CONCLUSION

In this brief survey there has only been space to touch on some of the milestones in the literature of microchemistry. There is so much periodical literature available, especially in the three journals devoted to microchemistry: Mikrochemie (1923-1952), Mikrochimica Acta (1953- ) and the Microchemical Journal (1957- ). There are innumerable booklets of various kinds, such as the British Drug Houses’, B.D.H. Reagents for Delicate Analysis and “Spot” Tests (Figure 63), which was the instruction manual that accompanied the B.D.H. Spot Test Kit, from 1932 to just a few years ago.

Over the years, many hundreds of these useful microchemical tests have acquired names-usually the name of the originator, such as Fehling’s Solution, or Lugol’s iodine, etc. Compilations of these named reactions were published in book form as long ago as 1916, in Alfred Cohn’s Tests and Reagents, Chemical and Microscopical [Cohn, Alfred I. (1903)], and, in 1940, Merck published over 4,510 named reactions in the fifth edition of The Merck Index [Chemical, Clinico-Chemical Reactions, Tests and Reagents (1940); The tests described in Cohn’s book are actually a collection of named reactions published in a series of monthly installments in Merck’s Report, from March 1900 to September 1902. Since its first appearance in serial form (1903), the text matter was further greatly amplified for the 1916 publication. Cohn (1902) had previously published another useful book on Indicators and Test-Papers (Figure 64).

Following several articles by others on the use of squaric acid in microchemical tests, the squarates, which are the reaction products between squaric acid and some 40+ ions, have now been optically characterized by Jeffrey Hollifield, and his article, “Characterization of Squaric Acid Precipitates”, published in The Microscope, vol. 51:2 81-103 (2003), it demonstrates that new microchemical tests and procedures are being continuously devised and characterized.

Thus, microchemistry has been a valuable adjunct to microscopy continuously for about 180 years now. It continues into the new millennium, because there will always be microscopical chemists who realize that atoms are atoms, and the way they acted and reacted 180 years ago, is the same way they act and react today, and will continue to do so during the next 180 years. For as long as there are microscopes and chemicals, there will be microchemistry; what a powerful tool in the armamentarium of the microscopist, and what a fascinating body of literature to support it.

REFERENCES

Alimarin, I.P. and M. N. Petrikova (1960) Inorganic Ultramicro Analysis. Academy of Sciences. Moscow.

Alimarin, I.P. and W.N. Archangelskaja (1956) Qualitative Halbmikroanalyse. VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften. Berlin.

Behrens, H. (1894) A Manual of Microchemical Analysis. Macmillan. London.

Behrens, H. (1900) Mikrochemische Technik. Voss. Hamburg and Leipzig.

Behrens, H. and P.D.C. Kley (1921/1922) Organische Mikrochemische Analyse. L. Voss. Leipzig (1915) 4th Edition.

Behrens, H. and P.D.C. Kley (1969) Organische Mikrochemische Analyse. translated by Richard E. Stevens as Microscopical Identification of Organic Compounds. Microscope Publications Ltd., Chicago, Illinois.

Belcher, R. and C.L. Wilson (1946) Qualitative Inorganic Microanalysis. Longmans, Green & Company. London.

Belcher, R. and C.L. Wilson (1957) Inorganic Microanalysis; Qualitative and Quantitative. A Short Elementary Course. Longmans, Green & Company. London.

Benedetti-Pichler, A.A. (1942) Introduction to the Microtechnique of Inorganic Analysis. Wiley. New York. [Second printing, 1950].

Benedetti-Pichler, A.A. (1964) Identification of Materials via Physical Properties, Chemical Tests, and Microscopy. Academic Press, New York and Springer-Verlag, Vienna.

Benedetti-Pichler, A.A. and W.F. Spikes (1935) Introduction to the Microtechnique of Inorganic Qualitative Analysis. Microchemical Service. Douglaston, New York.

Boricky, Emanuel (1877) Elemente einer neuen chemischmikroskopischen Mineral- and Gesteinanalyse. Archiv der naturwissenschaftliche Landesdurchforschung von Böhmen, Band iii. Fr. Rivnac. Prague.

Chamot, É.M. (1915) Elementary Chemical Microscopy. Wiley. New York.

Chamot, É.M. (1921) Elementary Chemical Microscopy. Second Edition. Wiley. New York.

Chamot, É.M. (1922) The Microscopy of Small Arms Primers. Cornell Publications Printing Co., Ithaca, New York.

Chamot, É.M. and C.W Mason (1958) Handbook of Chemical Microscopy. Third Edition, Volume 1 only. Wiley. New York.

Chamot, É.M. and C.W. Mason (1930/1931) Handbook of Chemical Microscopy. Wiley. New York.

Chamot, É.M. and C.W. Mason (1938/1940) Handbook of Chemical Microscopy. Second Edition. Wiley. New York.

Chemical, Clinico-Chemical Reactions, Tests and Reagents (1940) A 367-page Table (pages 623-990) in the Fifth Edition of The Merck Index.

Cohn, Alfred I. (1899, 1902) Indicators and Test-Papers. Wiley. New York.

Cohn, Alfred I. (1903/1916) Tests and Reagents, Chemical and Microscopical Wiley. New York.

Davy, W. Myron and C. Mason Farnham (1920) Microscopic Examination of the Ore Minerals. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Donau, Julius (1913) Arbeitsmethoden der Mikrochemie, mit besonderer Berucksichtigung der quantitative Gewichtsanalyse. Geschaftsstelle des Mikrokosmos. Stuttgart.

Emich, F. (1911) Lehrbuch der Mikrochemie. J.F. Bergmann. Wiesbaden.

Emich, F. (1924) Mikrochemisches Praktikum. Second Edition. J.F. Bergmann. Munich.

Emich, F. (1926) Lehrbuch der Mikrochemie. Second Edition. J.F. Bergmann. Munich.

Emich, F. (1931) Mikrochemisches Praktikum. J.F. Bergmann. Munich.

Emich, F. (1932) Microchemical Laboratory Manual, with a section on Spot Analysis by Fritz Feigl. Translated by Frank Schneider. Wiley. New York.

Feigl, Fritz (1931) Qualitative Analyse mit Hilfe von Tupfelreaktionen. Akademische Verlagsgsellschaft. Leipzig.

Feigl, Fritz (1939) Qualitative Analysis by Spot Tests; Inorganic and Organic Applications. Second English Edition translated from the Third German edition. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Feigl, Fritz and Vinzenz Anger (1972) Spot Tests in Inorganic Analysis. Sixth Edition. Translated by Ralph E. Oesper. Elsevier. Amsterdam. [First Edition 1937; Second Edition 1939; Third Edition 1946, Fourth Edition 1954, Fifth Edition 1958].

Feigl, Fritz. (1937/1939/1946/1954/1956/1960) Spot Tests in Organic Analysis. Seventh English edition. In collaboration with Vinzenz Anger. Translated By Ralph E. Oesper. Elsevier. Amsterdam. 1966.

Feigl, Fritz (1949) Chemistry of Specific, Selective and Sensitive Reactions. Translated by Ralph E. Oesper. Academic Press. New York.

Fulton, Charles C. (1969) Modern Microcrystal Tests For Drugs. Wiley-Interscience. New York.

Geilmann, W. (1934/1954/1960) Bilder zur qualitative Mikroanalyse anorganischer Stoffe. Verlag Chemie. Weinheim.

Grant, Julius (1946) Quantitative Organic Microanalysis Based on the Methods of Fritz Pregl. Fourth English edition revised and edited by Julius Grant. Blakiston. Philadelphia. [First Edition 1924; Second 1930; Third 1936; Fifth 1951].

Grey, Egerton C. (1925) Practical Chemistry by Micro-Methods. Heffer. Cambridge.

Haushofer, K. (1885) Mikroskopische Reactionen. Eine Anleitung zur Erkennung verschiedener Elemente unter dem Mikroskop als Supplement der qualitativen Analyse. Vieweg, Munich.

Helwig, A. (1865) Das Mikroskop in der Toxikologie. Mainz.

Hinrichs, Carl Gustav (1904) First Course in Microchemical Analysis. C.G. Hinrichs, Publ., St. Louis, MO; Lemcke and Buechner, New York and Leipzig; H. Grevel and Company, London; H. LeSoudier, Paris.

Hollifield, Jeffrey M. (2003) Characterization of Squaric Acid Precipitates. The Microscope 51:2 81-103.

Holmes, Andrew (2002) Rapid Spot Testing of Metals, Alloys and Coatings. ASM International, Materials Park, Ohio.

Huysse, A.C. (1900) Atlas zum Gebrauche bei der mikrochemischen Analyse fur Chemiker, Pharmaceuten, Bergund Huttenmknner, Laboratorien an Universitdten and Technischen Hochschulen. Brill. Leiden.

Huysse, A.C. (1932) Atlas zum Gebrauche bei der mikrochemischen Analyse fur Chemiker, Pharmaceuten, Bergund Huttenmdnner, Laboratorien an Universitdten and Technischen Hochschulen. Second Edition. Brill. Leiden.

Inorganic Analysis. Sixth Edition. Translated by Ralph E. Oesper. Elsevier. Amsterdam. 1972. [First Edition 1937; Second Edition 1939; Third Edition 1946, Fourth Edition 1954; Fifth Edition 1958].

Jungreis, Ervin (1984/1997) Spot Test Analysis; Clinical, Environmental, Forensic, and Geochemical Applications. Second Edition. Wiley-Interscience. New York.

Keune, Hans (1967) Bilderatlas zur qualitativen anorganischen Mikroanalyse. VEB Deutscher Verlag fur Grundstoffindustrie. Leipzig.

Kirk, Paul L. (1950) Quantitative Ultramicroanalysis. Wiley. New York.

Kley, P.D.C. (1915) Tabellen zur systematischen Bestimmungder Mineralien, Part 2 of Behrens-Kley Mikrochemische Analyse. Voss, Leipzig and Hamburg.

Kley, P.D.C. (1921) Behrens-Kley Mikrochemische Analyse. Third Edition. Voss, Leipzig.

Klément, C. and A. Rénard (1886) Reactions Microchimiques; a Cristaux et leur Application en Analyse Qualitative. Manceaux, Brusselles.

Kofler L., and A. Kofler (1954) Thermomikromethoden, Third Editio n. Verlag Chemie. Weinheim.

Kofler, L. and Adelheid Kofler (1948) Mikromethoden zur Kennzeichnung organischer Stoffe and Stoffgemische. Wagner. Innsbruck.

Kofler, L., A. Kofler and Mayrhofer, A. (1936) Mikroskopische Methoden in der Mikrochemie. Haim. Vienna.

Korenman, I.M. (1965) Introduction to Quantitative Ultramicroanalysis. Academic Press. New York.

Kuhnert-Brandstätter, Maria (1971) Thermomicroscopy in the Analysis of Pharmaceuticals. Pergamon Press. Oxford.

Laitinen, H.A. and G.W. Ewing, Eds (1977) A History of Analytical Chemistry. Division of Analytical Chemistry, American Chemical Society; Maple Press. York, PA.

Lehmann, Otto. (1891) Die Kristalanalyse. Englemann. Leipzig.

Malissa, H. and A.A. Benedetti-Pichler (1958) Anorgansche qualitative Mikroanalyse. Springer Verlag. Vienna.

Maljaroff, K.L. (1953/1954) Qualitativeanorganische Mikroanalyse. Verlag Technik. Berlin.

Mason, C.W. (1983) Handbook of Chemical Microscopy. Fourth Edition, Volume 1 only. Wiley. New York.

Mayrhofer, A. (1923) Mikrochemie der Arzneimittel and Gifte;Die offizinellen anorganischen und organischen Sauren und ihre Salze. Urban and Schwarzenberg. Vienna.

Mayrhofer, A. (1928) Mikrochemie der Arzneimittel and Gifte;Die arzueimittel organischer Natur. Urgan and Schwarzenberg, Vienna.

McCrone, W.C. (1956) Fusion Methods in Chemical Microscopy. Interscience. New York.

Molisch, Hans (1923) Mikrochemie der Pflanze. Third Edition Gustav Fischer, Jena.

Niederl, J.B. and V. Niederl (1938) Micromethods of Quantitative Organic Elementary Analysis. Wiley. New York.

Orange, A. P.W. James, and F.J. White (2001) Microchemical Methods for the Identification of Lichens. British Lichen Society.

Pregl, Fritz (1924) Quantitative Organic Microanalysis. translated from the Second German Edition by Ernest Fyleman. Churchill. London.

Raspail, Francois-Vincent (1827) Experiences de chimie microscopique ayant pour but de demontrer 1’analogie qui existe entre la deposition qu’affecte la silice dans les spongilles et dans certames eponges…. Mem. Soc. Hist. Nat. 204-237.

Raspail, Francois-Vincent (1833) Nouveau SysOme de Chimie Organique, Fonde sur des Methodes Nouvelles d’Observation; Bailliere. Paris.

Raspail, Francois-Vincent (1834) A New System of Organic Chemistry… with Notes and

Rosenthaler, Leopold (1922) Qualitative Pharmazeutische Analyse. Ferdinand Enke,

Stuttgart. Additions; Trans. William Henderson. Sherwood, Gilbert, & Piper. London.

Rosenthaler, Leopold (1928) Grundzuge der Chemischen Pflanzenuntersuchung. Third Edition. Julius Springer, Berlin.

Rosenthaler, Leopold (1930) The Chemical Investigation of Plants. Translated into English by Sudhamoy Ghosh, from the Third German edition. Bell and Sons, Ltd. London.

Rosenthaler, Leopold (1935) Toxikologische Mikroanalyse; Qualitative Mikrochemie der Gifte u.a. gerichtlich-chemisch wichtiger Stoffe. Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin.

Schaeffer, Harold F. (1953) Microscopy For Chemists. Van Nostrand. New York.

Schneider, F.L. (1946) Organic Qualitative Analysis. Wiley. New York.

Schneider, Frank L. (1964) Qualitative Organic Microanalysis; Cognition and Recognition of Carbon Compounds. Academic Press, New York and Springer-Verlag, Vienna.

Schoorl, N. (1909) Beiträge zur mikrochemischen Analyse (A collection of papers published in Z. analyt. Chem. Vol. 46, 47, 48 in the years 1907-1909). Kreidl. Wiesbaden.

Schramm, Hans-Peter and Bernd Hering (1988; reprinted 1995, 2000) Historische Malmaterialien und ihre Identifizierung. Ravensburger Buchverlag, Stuttgart.

Short, M.N. (1940) Microscopic Determination of the Ore Minerals. Second Edition. USGPO, Washington, DC.

Stephenson, Charles H. (1921) Some Microchemical Tests for Alkaloids. Including Chemical Tests of the Alkaloids Used, C.E. Parker. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Svehla, G., Editor (1980) Organic Spot Test Analysis, Vol. X of Wilson and Wilson’s Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Tunmann, Otto (1913) Pflanzenmikrochemie. Borntraeger, Berlin. A second edition was published in 1922.

Weiner, Dora B. (1968) Raspail, Scientist and Reformer; Columbia University Press. New York.

Weisz, Herbert. (1961/1970) Microanalysis by the Ring-oven Technique. Pergamon Press. Oxford.

Wenger, P.E. et alii (1948) Reagents for Qualitative Inorganic Analysis. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Wilson, Cecil L. (1938) An Introduction to Microchemical Methods for Senior Students of Chemistry. Methuen. London.

Winchell, N.H. (1892) The Elements of a New Method of ChemicoMicroscopic Analysis of Rocks and Minerals. N.H. Winchell’s Translation of Boricky’s Elemente…. above. 19th Annual Report of the Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota for 1890. Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Wormley, Theodore G., M.D. (1867) Micro-Chemistry of Poisons…. William Wood & Co. New York.

Wormley, Theodore G., M.D. (1885) Micro-Chemistry of Poisons…. Second Edition. J.B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia.

Comments

add comment