Vintage Visits: Taking a Closer Look at Bourgogne Paper-wrapped Microscope Slides

In a previous article we featured an antique microscope slide prepared during the historic H.M.S. Challenger expedition. The Challenger slide is one of many vintage microscope preparations in the Brooks Collection of Antique Microscopes. The slides were acquired over the years through individual purchases or given as gifts to Don Brooks.

In future issues of Nanographia, we will make vintage visits to our antique microscope slides collection and share them with you. Our intention is not to repeat previous research by those such as Brian Bracegirdle and James B. McCormick; it is more in the spirit of Howard Lynk’s approach to antique microscope slide collecting, offering a glimpse of an earlier age.

In this article, we visit a handful of Victorian-era slides wrapped in ornamental paper made by members of the Bourgogne family—a group of famous slide “mounters” as they were called in the profession. The Bourgognes’ microscope slide making operation was based in Paris during the mid-to-late 1800s. There are eight paper-wrapped Bourgogne slides in the Brooks collection. Let’s pay them a visit.

The Original Wrappers

Wrapping prepared microscope slides in paper served as a practical way to hold down the coverglass and specimen to the slide prior to the introduction of Canada Balsam mounting medium, but the practice of wrapping slides in paper was continued for many decades, largely due to its aesthetic appeal.

Most of the paper-wrapped Bourgogne slides in our collection are smaller than the standard 3” x 1” slide established by the Royal Microscopical Society (RMS). The size variation is described in Andrew Pritchard’s 1847 anonymously printed book Microscopic Objects: Animal, Vegetable and Mineral: With Instructions for Preparing and Viewing Them.

Notice that Pritchard refers to himself in the third person, perhaps, because he published his book anonymously:

“…No. 1 size, 3 inches long by 7/8 of an inch wide; No. 2 size, 2 inches long and 5/8 wide; No. 3, 1 ½ inch long by ¼ of an inch wide. The latter size is seldom used except for opaque bodies, as hereinafter mentioned. The reason assigned by Mr. Pritchard for selecting these lengths was that they are multipliers of each other, and therefore the drawers or boxes containing them can be made of uniform sizes. The Royal Microscopical Society of London has adopted the length of the first as standard—that is 3 inches.”

With the establishment of the new RMS standard, Pritchard still makes an argument for maintaining the No. 2 size microscope slide, arguing the smaller size slides require less material to make the slide and takes up less space in the slide cabinet:

“The No. 2 slides are sometimes preferred as containing less than one-half the glass and occupying a like reduced proportion of space.”

Like the 1980s debate over Betamax vs VHS formats, the RMS No. 1 size microscope slide eventually won the day.

Great Explanations

Up until the late 1990s, not much was known about Joseph Bourgogne and his slide-making business, which would eventually include his three sons. Brian Bracegirdle’s beautiful and comprehensive 1998 book Microscopical Mounts and Mounters contained little historical information about Bourgogne. At the time of the book’s publication, Bracegirdle didn’t have access to today’s modern resources, like Google Books, to search for obscure out-of-print publications containing the name Bourgogne. One such source, commonly cited after 1998, is an essay by the Reverend Edmund Dixon published in Charles Dickens’ weekly magazine Household Words.

Dixon’s essay is beautifully written and gives an eloquent appreciation for the art of microscope slide making, along with some buyers’ advice about prepared slides in general. Within the essay are a few valuable gems of information about Bourgogne’s slide-making business. Below, we highlight some Bourgogne-specific quotes from Dixon’s essay. You can access the entire piece, and for a deeper dive on all things Bourgogne, be sure to check out this excellent article by Brian Stevenson.

Here is what Dixon had to say about Bourgogne’s work:

“Amongst continental preparers, Joseph Bourgogne, of Rue Notre-Dame, Paris stands preeminent. He is a man whose whole soul is in his art, and he naturally speaks of microscopic preparation as one of the most important aids to sciences…As we treasure cabinet-pictures by Teniers or the Breughels, so shall we set an exalted value on charming bits of still-life from the studios of Amadio or Stevens, on insect-portraits by Topping, on botanical groups by Bourgogne the Elder, and on other works by anonymous artists.”

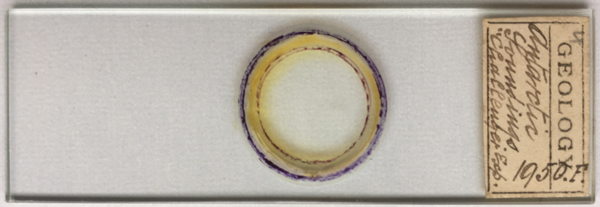

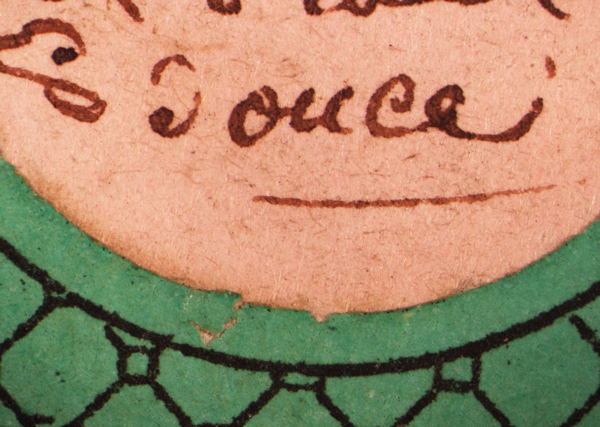

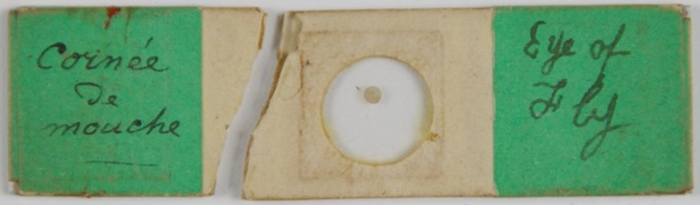

Notice that Dixon refers to the slide mounters of the day as “artists”. The Bourgogne microscope slide pictured below, wrapped in his signature ornamental paper, is indeed a work of art, suitable for framing.

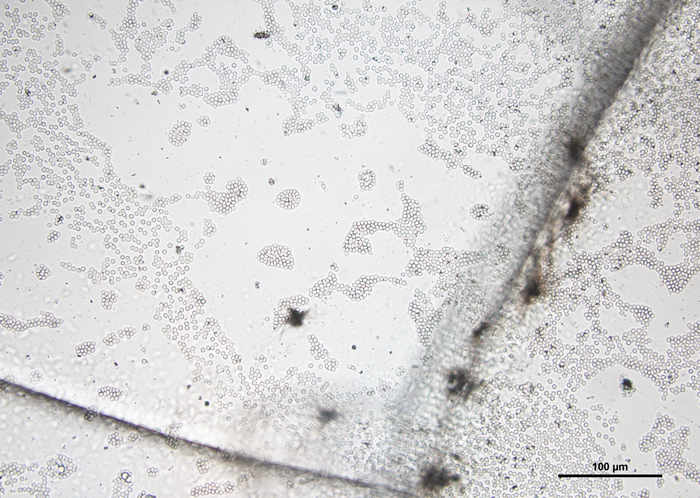

The sample is Batrachospermum, a freshwater red alga that appears to have been prepared dry and initially attached to the coverglass. Looking closely at the photomicrograph below, you can see where the sample has pulled away from the coverglass, leaving behind a sort of negative image of where the sample had been originally placed.

Aside from the sheer beauty of the presentation of this Bourgogne slide, we also found its construction clever and perhaps underappreciated regarding the slide’s labeling methods. Notice the slide is first wrapped in an off-white paper and labeled. Then a layer of ornamental paper is applied to the top of the slide with corresponding holes punched out to reveal the name of the specimen.

There is virtually no chance of the slide label falling off…a laborious task, but worth the effort when considering the three-dimensional quality of the paper in the final presentation of the preparation.

The next two slides are the smaller size No. 2 variety made by Joseph Bourgogne. The printed geometric design is the like the green paper, but these are yellow in color.

Private Labels

Since Bourgogne’s slide labels couldn’t be easily removed, it seems resellers would commonly cover the specimen’s name written in French with one written in English. Sometimes the Bourgogne name was retained, as perhaps an indication to quality of the preparation, while other times the additional labels cover the Bourgogne name with the English translation of the French slide label.

This preparation of human blood has a cracked coverglass, but the specimen is still well intact.

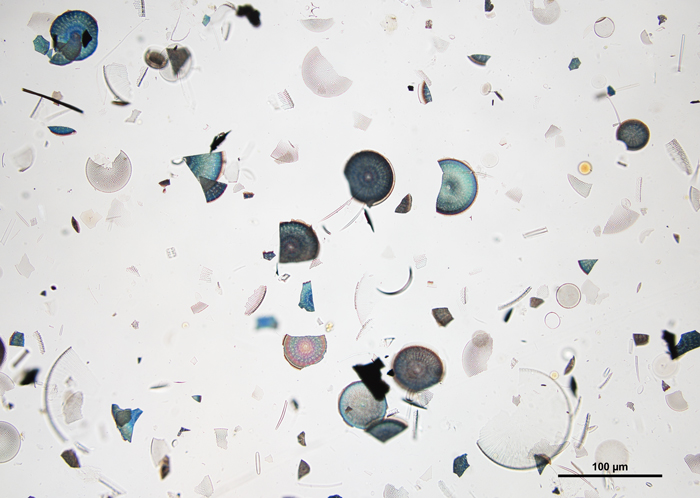

Translating the French labels isn’t always easy even with the assistance of Google Translate tool. Such was the case with the next No. 2 Bourgogne slide pictured below. The first word is “Guano”, but the second word gave us a bit of a problem. Dixon’s essay sheds light on the mysterious word:

“But, one of these days, as my readers who live long enough will see, beautiful preparations of first-rate hands will pass through the same course of destiny as illuminated missals, majolica earthenware, Benvenuto Cellini carvings and the like…we should have speculators buying up diatoms from Ichaboe guano, and causing them to disappear as the substance itself grows scarcer, and the present microscopic preparations from the list of works by the ‘old masters’.”

From Dixon’s essay and a quick Google search, we learned that Ichaboe is the name of an island off the coast of Namibia; not a French word.

Buyer Beware

Our next Bourgogne slide visit is not very pleasing to the eye. The slide lacks the beautiful ornamental paper and elegant three-dimensional punch-outs of the slide label, and the Bourgogne brand name. Without the Bourgogne name, how can we be sure this ragtag-looking preparation can be attributed to the famous slide mounter?

For guidance, we turn again to Bracegirdle’s book Microscopical Mounts and Mounters. He describes some of the slides pictured in his book, which lack the Bourgogne name, as being attributed to or reminiscent of Bourgogne based on the slide’s construction and appearance of French labeling. For the above preparation and the one that follows, we used the same line of reasoning and are attributing these two paper-wrapped slides to Bourgogne.

In addition, from Dixon’s essay, we may also conclude that some of these not-so-good preparations attributed to Bourgogne might be the second and third choice offerings, which Bourgogne made available at an attractive price:

“M. Bourgogne’s best preparations are excellent, with the merit of being determined and named; his inferior preparations are very indifferent, full of bubbles and dirt…M. Bourgogne classes his productions into first, second, and third-choice specimens…Just so we may suppose that M. Bourgogne’s third-choice preparations—some as low as threepence-halfpenny each.”

As you can see from the photomicrographs, these specimens are bubble-free and are generally clean. At that price, a lack of nice paper and a substandard preparation makes it a bit more palatable.

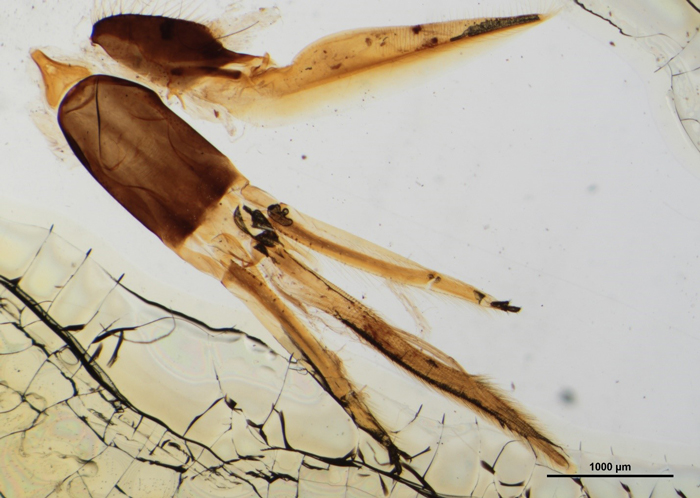

Analysis of the Broken Bourgogne

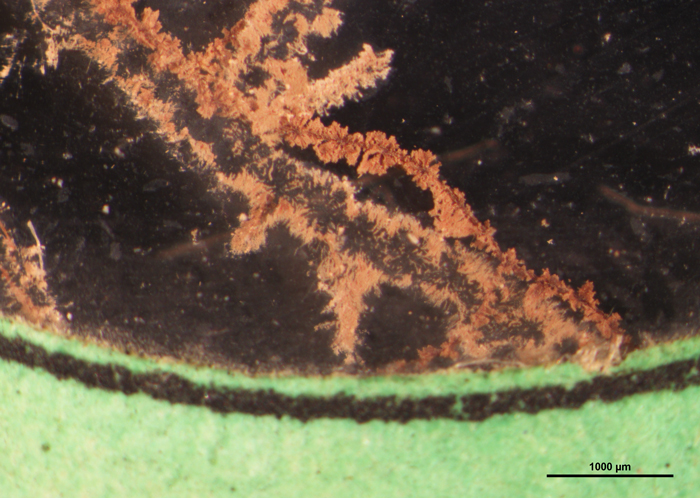

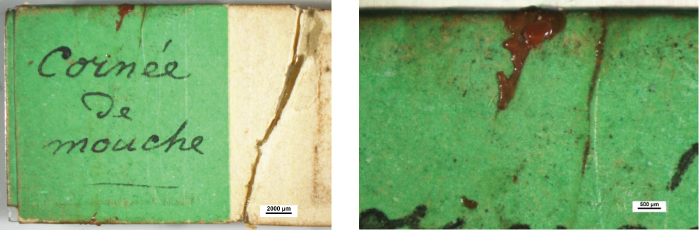

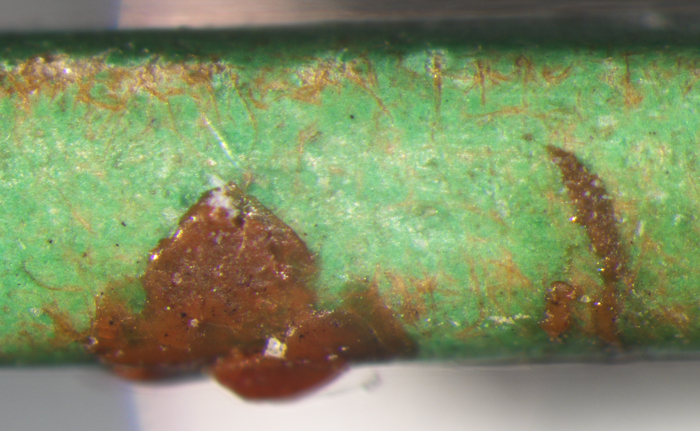

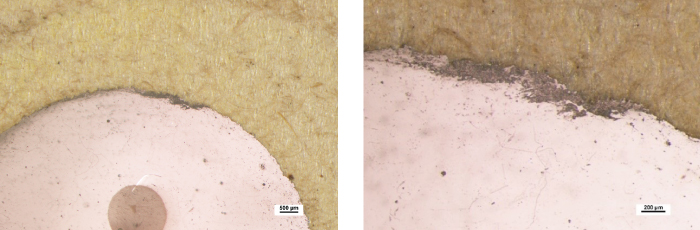

Our next visit is to a broken slide attributed to Bourgogne. It’s unclear whether the slide was purchased this way or was broken in shipping. Nevertheless, while looking at the two halves of the slide, we noticed the portion on the left had a bit of red material just above the first word of the specimen’s name. So naturally, we wanted to look at it microscopically.

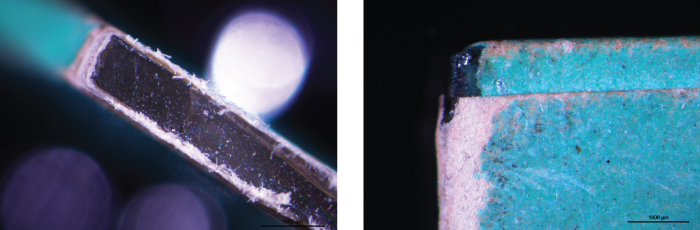

We know from Bracegirdle that early slide mounters would apply a bead of red sealing wax around the perimeter on top of a slide, place the specimen in the center, and then sandwich the preparation with a second slide, sealing the specimen between the two slides. This slide, like the other Bourgogne preparations, is made from a single slide, not two, and there was no evidence of red sealing wax being used as an adhesive for the paper wrapping.

Since the slide was broken in half, we were able to check out a full cross section of the slide and searched for evidence of red wax perhaps being used as an adhesive for the paper wrapping. We also examined the corners of the slide where the paper had been folded for traces of red wax seeping out from the corners. On both accounts we found no evidence of red sealing wax.

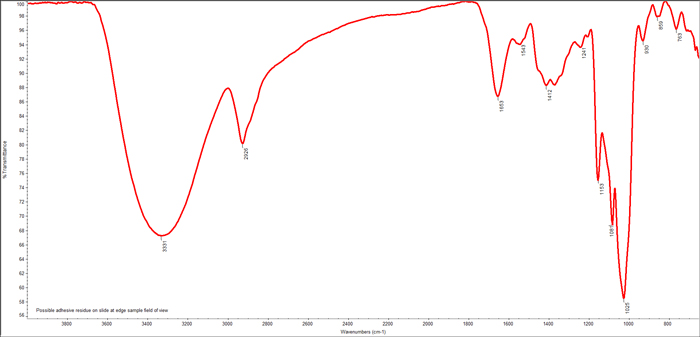

Below is the infrared spectrum of the red material, which appears to be a sealing wax material.

We also sampled some of the adhesive near the junction of the coverslip and off-white paper and found it to be a starch, likely from a starch-based paste.

That’s a Wrap

As our visit to the Bourgogne slides draws to a close, we will leave you with one last quote from Reverend Dixon:

“One great merit of the modern microscope is their portability; if the reader wishes to test their attractiveness, let him arrive some rainy day at a country house full of company, when the guests are prevented from enjoying out-door amusements. Let him there produce…a box full of good preparations, and he will work wonders.”

Comments

add comment