Ink Analysis: The Archaic Mark

At a Glance

The University of Chicago consulted with McCrone Associates to authenticate the codex of the Gospel of Mark, also called the “Archaic Mark,” and helped identify it as a forgery.

Situation

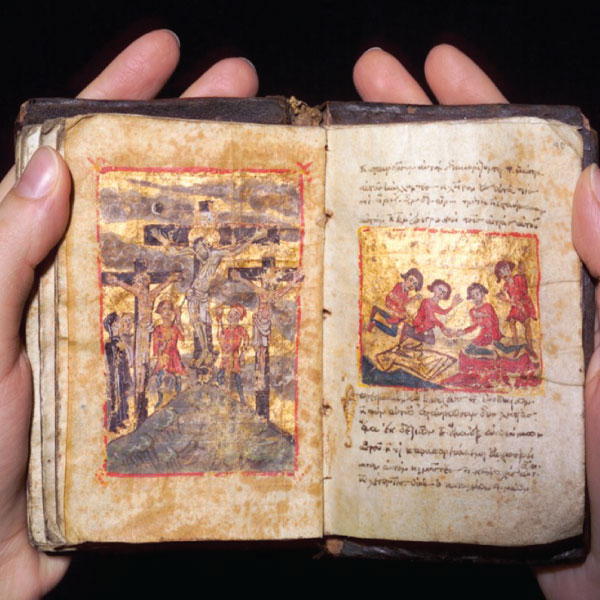

The codex of the Gospel of Mark contains the entire text of this New Testament Gospel. The miniscule text covers 44 pages and is accompanied by 16 tiny color illustrations. Also known as the Archaic Mark, some major scholars dated the codex to the 14th century.

Issue

As early as 1947, scholars began to question whether the miniature codex was an authentic Byzantine manuscript, preserving a very early text of the Gospel of Mark, or a modern forgery.

Suspicions that the codex was not authentic arose because its Greek text suggested that it was derived from a 19th century critical edition of the Greek New Testament.

Furthermore, researchers discovered Prussian blue, a modern ink pigment, embedded in one of the miniature illustrations. However, many argued the pigment came from attempts to retouch the document during restoration and were not part of its original construction.

In 2005, the University of Chicago Library digitized the Archaic Mark, making it available to scholars worldwide and stimulating renewed interest in the document.

The library also arranged for a complete and definitive examination of the material components of the codex:

- microscopical and chemical testing by McCrone Associates

- codicological testing (the study of how books are constructed) by Ms. Abigail B. Quandt, Senior Conservator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore

- textual analysis by Margaret M. Mitchell, the University of Chicago Divinity School.

“We chose McCrone Associates for its internationally recognized

status as a microanalysis leader in conservation with

similar projects, like the Gospel of Judas”

No stranger to high profile cases, McCrone Associates had performed analysis on the Shroud of Turin, which many believed was the burial shroud of Jesus; the Vinland Map, a supposed ancient rendering of the New World; and the Gospel of Judas, another ancient codex determined to be authentic.

Solution

Starting in January 2009, a team of McCrone Associates scientists led by Joseph G. Barabe, Senior Research Microscopist examined the manuscript at the University of Chicago Regenstein Library, The Special Collections Research Center.

He took 24 samples of parchment, ink and a range of paints used in illustrations from the codex to determine its authenticity. Examinations were completed at both the University of Chicago Library and McCrone Associates’ laboratory in Westmont, Ill.

Using a stereomicroscope, Barabe saw no evidence of retouching in the manuscript and that all of the paint in the illustrations appeared to be original. This observation was later confirmed by additional testing and seemed to disprove earlier suspicions that any modern pigments found in the manuscript were the result of restoration attempts.

The samples were then subjected to a battery of microanalytical techniques, including polarized light (PLM), energy dispersive x-ray spectrometry (EDS) in the scanning electron microscope (SEM) for elemental analysis, X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy.

Using PLM, scientists sampled light, medium and dark samples of blue paint and found that the dominant blue pigment in the miniatures was Prussian blue. Prussian blue was invented in 1704 and was commercially available by the 1720s. They also found trace amounts of synthetic ultramarine blue, a pigment only available commercially since the late 1820s.

When examining the illustrations with ultraviolet light, Barabe noted that the white and near white areas of all of the paintings fluoresced a bright blue-green. This suggested the possible presence of zinc white, a fluorescent white pigment.

Subsequent analysis of a sample of the white paint by both PLM and FTIR confirmed the presence of zinc white, a pigment not commonly available until about 1825. This opaque white pigment has been known since antiquity, but it was not suggested for use as a pigment until about 1780, and was not used extensively as an artist’s pigment until the second quarter of the 19th century.

Although zinc white, also called zinc oxide, was found in just one sample, scientists used SEM-EDS to determine that most of the paint samples contained an almost-white cream pigment that included a combination of the elements zinc, barium, and sulfur. XRD confirmed the presence of zinc sulfide, another fluorescent pigment, and one of the key components of lithopone, which was not available until 1874.

Using EDS and SEM, scientists found an iron gall component in the samples. Rich in both iron and sulfur, iron gall inks have been identified in documents as early as the 3rd century and have been common since the 6th century.

Barabe submitted samples to the Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the University of Arizona for carbon dating which reported the animals from which the parchment was made most likely died somewhere between the 15th and 17th centuries.

“For the first time, there was a comprehensive chemical examination of all the components of the codex, and using the benefits of modern microanalytical instruments and techniques, we gave scientific evidence to what were only speculations about the manuscript’s authenticity,” said Barabe.

Results

McCrone Associates concluded that the “Archaic Mark” codex was created after 1874 using materials not available until the late 19th century on a parchment substrate dating from about the middle of the 16th century.

The rest of the authentication team corroborated with McCrone Associates’ conclusions.

Ms. Quandt used codicological analysis to reconstruct the steps taken by the modern forger to produce the manuscript.

Dr. Mitchell identified the text from which the forger copied the information provided in the codex. Mitchell confirmed that the forger used an 1860 edition of the Greek New Testament by Phillip Buttman, Novum Testamentum Graece.

The team’s findings will be published in the scholarly journal Novum Testamentum in February 2010.