Vintage Visits: An Exploration of John Charles Stovin’s “The Micrograph”

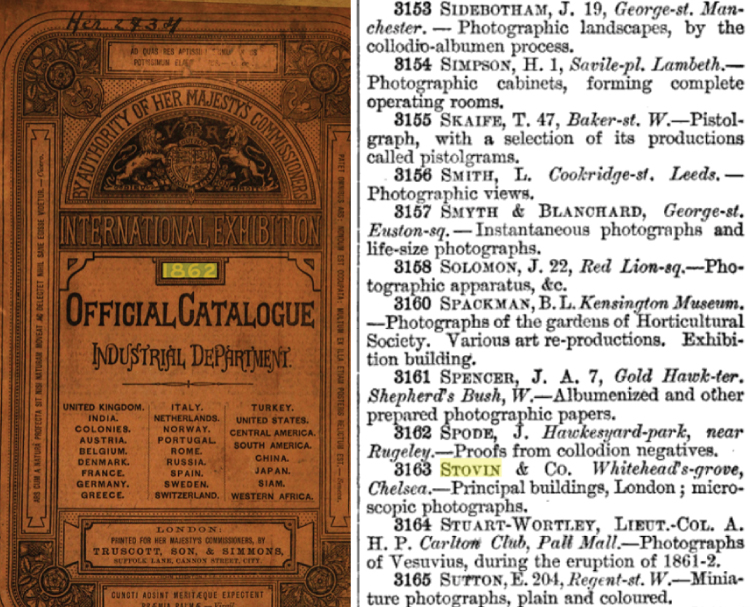

A visit to the Brooks Collection of Antique Microscopes and Rare Books can send you down some interesting and unexpected historical paths. Such was the case while learning about the rare and early set of microphotographic discs and spyglass attributed to John Charles Stovin pictured above. This pocket-sized product, which Stovin called “The Micrograph”, featured a burgundy-colored velvet-lined box along with a miniature ivory spyglass for viewing the microphotographs discs contained within. Stovin’s Micrograph sets were displayed and possibly sold to the public at The Great International Exhibition held in London in 1862. I say possibly sold because vendors at The Great Exhibition weren’t supposed to sell their wares, but many of them did. Only seven known sets of Stovin’s Micrograph with the ivory spyglass are known to exist, along with two other sets having a similar spyglass made of turned wood. This article explores Stovin’s rare entertaining gadget and its set of microphotographs, but first, let’s describe some terms.

A Matter of Words Mattering

One of my first professional development courses in microscopy was a photomicrography class taught by John Gustav Delly. The textbook for the course was Delly’s classic Kodak® publication “Photography Through the Microscope” in which the first word of the book’s introduction is Photomicrography with an asterisk—”Photomicrography*”. Here, Delly emphasizes the difference between photomicrography and microphotography, and why they can sometimes be confused…

“Photomicrography* should not be confused with microphotography, which involves making extremely small photographic images of large objects. The distinction between the terms photomicrography and microphotography was made as early as 1858, but the confusion persists. A contributing factor in the confusion is faulty translation from the German language in which photomicrography is Die Mikrophotographie.”

Adding to this bit of confusion, is our set of microphotographic discs and spyglass Stovin named The Micrograph and he referred to each of the individual microphotographic discs in the set as a “Microgram”.

Are They Stovin or Are They Dancer?

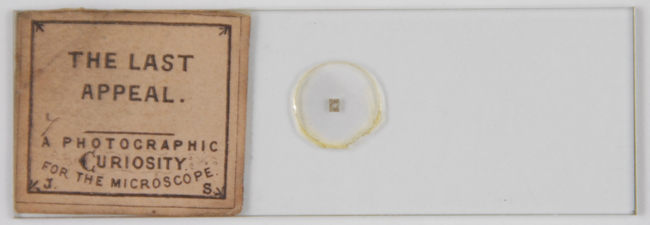

Usually, most microphotographs are mounted on a labeled 3” x 1” microscope slide because a microscope is needed to view the microscopic image like the Stovin slide and microphotograph pictured below.

Stovin’s Micrograph sets eliminated the need for a microscope by supplying users with a spyglass for viewing. With such a small footprint, users could slip the entire collection of microphotographs and viewer in a coat pocket, making for a mobile form of entertainment.

The downside of such a gadget is that there are no labels on the microphotographs and no other identifying characteristics attributing these sets to Stovin, which is why up until recently, historians had credited these Micrograph sets to John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer was and still is the most famous maker of microphotographs, but in a well-documented article by Stanley Warren appearing in a 2014 issue of Micro Miscellanea, the Newsletter of the Manchester Microscopical and Natural History Society, Warren makes a convincing case that these Micrographs were made by John Charles Stovin.

Warren’s argument for Stovin as the creator is based on two pieces of evidence: the 1862 exhibitors list from The Great International Exhibition where Stovin and Dancer displayed their goods, and two of the original handwritten lists of specimens that came with each Micrograph set.

For users to know which microphotographs were contained in a Micrograph’s set, Stovin supplied a small handwritten list of the specimens, but these tiny pieces of paper were usually lost over time. Warren’s article includes images of two surviving handwritten lists, which are both twenty-four-disc variety—one from an ivory spyglass set, and one from a wood-turned spyglass set. Stovin also sold Micrographs in twelve-disc sets, which is the type featured in this article, but three of the discs have been lost over the years by previous owners.

Editor’s Note: To view images of the paper insert and handwritten list of specimens, see images 4, 5 and 6 within this Facebook post—it is not necessary to have a Facebook account to view the images.

In addition to Warren’s publication, one of the best references about Stovin’s life and his microphotographs is this comprehensive article by Brian Stevenson, showcasing over one-hundred images of Stovin’s microphotographs, all sourced from labeled 3” x 1” microscopes slides. Using both articles, I matched the microphotograph titles from the handwritten lists in Warren’s article to the microphotographs pictured in Stevenson’s article, sort of like putting a name to a face. Since our Micrograph set did not contain the original handwritten list of specimens, I had to see for myself what microphotographs were in our set.

What Do We Have Here?

The ivory viewer that came with our Micrograph set was still in fine working condition, as you can see from the below image I captured on my phone, but for the purpose of this article, I used an Olympus BX51 and Nikon FI3 digital camera to capture images of the microphotographs.

Since the discs are a little smaller than a U.S. dime, they were a bit difficult to remove from the deep velvet slots of their case. My investigation of our photomicrographic disc started by placing them one by one on a 3” x 1” microscope slide and viewing the images through the microscope. While examining the microphotographs from our set, I began seeing many of the same images presented in Stevenson’s article, but there were also a few I had not seen before.

To get my bearings, I recreated the two handwritten lists from Warren’s article. The images which overlap between the ivory spyglass set and the wooden spyglass set are highlighted in green, below. Highlighted in orange are the Stovin discs contained in our set of nine. You will also notice one title highlighted in aqua. I’ll get to that one in a bit.

You can see our set contains only two of the Stovin microphotographs from the above lists, those images being “Madonna and Child” and “The Vintage“:

For the remaining discs in our set, I began matching them to the microphotographs in Stevenson’s article. Below is what I found.

The above four microphotographs confirmed by the images in Stevenson’s article still left three of our discs undescribed. In Warren’s article, he mentions a few rare titles, one being “Venice, the Customs House Entrance” (that’s the one I highlighted in aqua above). The image I was seeing through the microscope featured people in the foreground with docked ships and some government buildings in the background. Due to the rarity of the image, I was unable to compare our image to a reference image published online.

With no reference images, I based my best guess on scenes from paintings and photographs from the mid-1800s, as well as conferring with colleagues, and went with “Venice, the Customs House Entrance” for the title of the Stovin microphotograph below.

Hunting the Microphotograph

The next Stovin microphotograph image from our set was also a bit of a mystery. The image depicts a group of people riding elephants and hunting a tiger. I found an almost identical image in the publication “Das Buch Der Welt (The Book of the World)”, published in 1860. “Das Buch Der Welt” was a yearly publication, an encyclopedia of sorts, with images sprinkled throughout. The image titled “The Tiger Hunt in India Using Elephants” (title by Getty Images) is nearly the same as the Stovin microphotograph pictured below.

Notice, most of the scene and characters are the same except for an elephant on the right along with a few changes in the background, but the people and animals in the foreground are unchanged.

I found a similar occurrence in Stevenson’s article when comparing Stovin’s microphotograph titled Hunting the Boa Constrictor in America, with a near copy of an illustration again from “Das Buch Der Welt” titled “Natives Fighting a Huge Snake” (title by Getty Images), published in the 1859 edition. If you look at the images closely, they aren’t quite the same, but again the people and snake are nearly identical.

Not related to our Micrograph discussion, but perhaps an explanation for the differences between the original paintings used in “Das Buch Der Welt” and Stovin’s microphotographs, is the practice of making steel engraved copies of color paintings. I found an example of this when comparing the Stovin’s microphotograph “Happy as a King”, which is from an image published in the 1862 edition of “Das Buch Der Welt”, (page 352) to the original painting “Happy as a King” by William Collins in 1836. Collins’ painting was copied as a steel engraving and given the new title “The Old Farm Gate“. Notice that a dog has been added in the lower left corner of the steel-engraved image.

A post by the History of Microscopy Facebook Group explains why steel engraved copies of paintings were made:

“ca. 1860 microphotograph slide by John Charles Stovin (1814-1896), London. Stovin variously identified his microphotographs with his initials, ’J.C.S.’ or ’J.S.’

The photograph is based on David Wilkie’s 1806 painting ’The Village Politicians‘. However, it is difficult or impossible to produce clear microphotographs from color paintings. Instead, microphotographs were generally produced from black/white prints of engraved copies of paintings. Prints from engravings were mass-produced, allowing large numbers of people to have artworks in their homes. Importantly for photographers, engravings have strong contrasts and cleanly-defined lines that show up well as microphotographs. In this case, Stovin photographed a print of Abraham Reimbach’s 1813 reproduction of Wilkie’s work.”

Perhaps steel engravers sometimes took the liberty of making slight changes to the original paintings? This would explain the variations we see between the original paintings of “The Tiger Hunt” and “Hunting the Boa”, and the final microphotographic images made by Stovin.

The last Stovin microphotographic disc in our Micrograph set is an image of the front page of The Photographic News, published June 29, 1860. Like “The Tiger Hunt”, I couldn’t find a published description or occurrence of this image.

So, it appears that our Micrograph set contains a mixture of several common Stovin microphotographs, along with one rare image and perhaps two one-of-a-kind images.

The Faded Past

Overall, I was surprised by how well-preserved our set of Stovin microphotographs appeared, showing no signs of degradation since being prepared in the early 1860s. Such was not the case for photographer and microscopist John Nicol. In the late 1800s, Nicol published the semi-regular column Notes from the North in The British Journal of Photography. In his March 25, 1881, column, Nicol describes and laments how his set of Stovin microphotographs did not stand the test of time (emphasis mine):

“Nearly twenty years ago I was presented by the maker, Mr. J.C. Stovin, of London, with a box of “London in Miniature”—a series of thirty-six microscope reductions of stereoscopic views of London—microphotographs mounted in the usual way on slips of glass with glass covers cemented on with Canada balsam…When I last saw them, some dozen years ago, they were still as beautiful as when first received…Since then the box has lain hid away in a drawer amongst unused lenses and antiquated apparatus until within a few days…To the unaided eye there appeared to be no visible change; but on placing the slips under the microscope the sad revelation was made…the beauty had fled, leaving hardly a wreck behind…the only cause for this unfortunate destruction…is that a trace of hypo, may have been left in the image.”

Not having processed a whole lot of images myself prior to the current digital age, I wasn’t sure what Nicol meant by the damaging effects of leaving “a trace of hypo” or what it might look like. Even Nicol seems uncertain, using the words “may have” when describing the possible cause of degradation. To me, it seems unlikely Stovin would have developed and processed all the images contained in Nicol’s set of thirty-six microphotographs incorrectly, since the source of Stovin’s subjects span a period of at least a couple of years. I was, however, able to track down a couple of examples of degraded Stovin microphotographs for sale on eBay, which perhaps illustrates what Nicol was seeing through his microscope in 1881.

Example #1, “The Village Politicians”.

Example #2, “Hunting the Polar Bear”.

In a closing sentence of Nicol’s column, he puts forth the idea of analyzing his set of degraded Stovin microphotographs to find the “ill-omened salt”:

“Small in quantity as the material is, I mean to carefully scrape off a number of faded images and look for that ill-omened salt, and hope on a future occasion to let my readers know the result.”

I was unable to find, at least in any future issues of The British Journal of Photography, of Nicol reporting-out his microscopical findings to his readers.

In seeing these degraded Stovin images on eBay, I thought, could these microphotographs have been the same ones purchased by Nicol from Stovin at the 1862 Great International Exhibition in London?

Microbes Ate My Microphotographs of Famous Microscopists

There is another explanation for the degradation of an entire set of microphotographs—microbial degradation. I recently examined a set of microphotographs made and prepared by the late Anthony DiDonato, a modern-day maker of microphotographs. The subject of DiDonato’s set features famous microscopists, and just about every image in the set of ten microphotographs is significantly degraded. Below is the DiDonato’s microphotograph “Robert Koch at Work”.

My colleagues and I will microscopically explore this set of microbial degraded microphotographs and report our findings in a future Vintage Visit.

As this Vintage Visit comes to an end, I’m reminded of how important it is to examine things with the microscope. I have often fielded questions from customers who are experiencing an issue with a particular analysis, and I ask, “What does it look like under the microscope?” To which they often reply, “I haven’t done that yet.” Whether it’s the degradation of microphotographs, or knowing which Stovin images we have in our Micrograph set, many questions can be answered by simply looking with a microscope.

Comments

add comment